July 14, 2023, 6:59 AM

July 14, 2023, 6:59 AM

Artificial intelligence (AI) is being used to make calls in which the voices of known people are imitated to scam the recipient.

These calls use what is known as generative AI, that is, systems capable of creating text, images or any other support, such as video, from the instructions of a user.

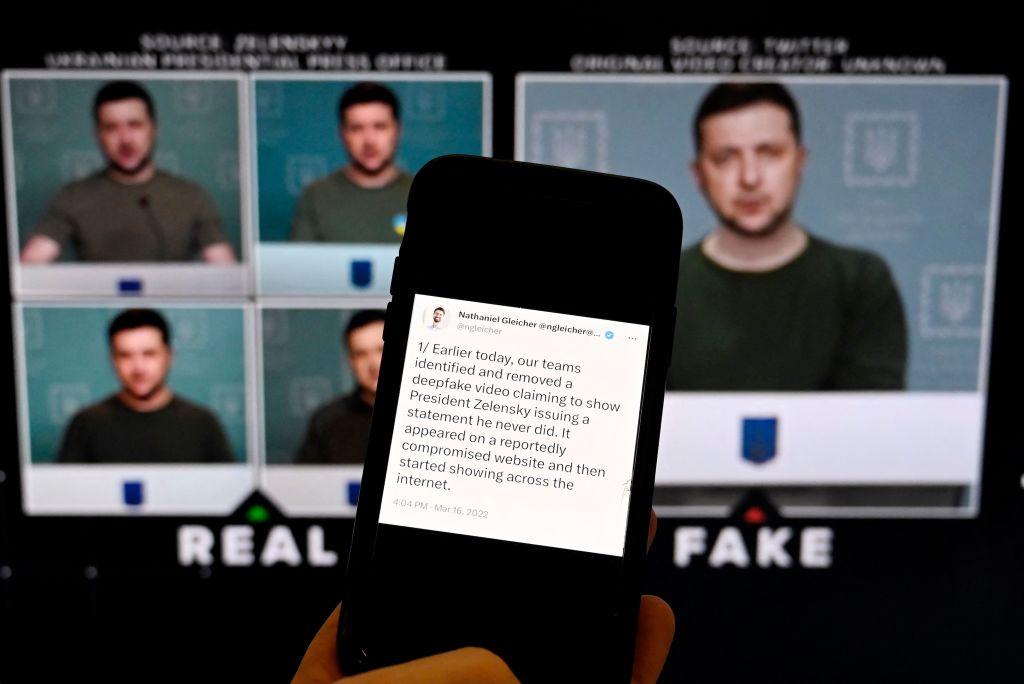

Deepfakes (deep fakes) have gained notoriety in recent years with a series of high-profile incidents, such as the use of the likeness of British actress Emma Watson in a series of suggestive ads that appeared on Facebook and Instagram.

There’s also the widely shared and debunked video from 2022, in which Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky appeared to tell Ukrainians to “lay down their arms.”

Now the technology to create fake audio, a realistic copy of a person’s voice, is becoming increasingly common.

Giving weapons to the enemy

To create a realistic copy of someone’s voice, data is needed to train the algorithm. This means having many audio recordings of the person’s voice.

The more examples of the person’s voice can be fed into the algorithms, the better and more convincing the final copy will be.

Many of us already share details of our daily lives on the internet. This means that the audio data needed to create a realistic copy of a voice could be readily available on social networks.

But what happens once the copy is out there? What is the worst that can happen? A deepfake algorithm could allow anyone who owns the data make “you” say what they want.

In practice, this can be as simple as typing some text and having the computer say it out loud as if it were your voice.

The main challenges

This possibility may increase the risk of increasing the prevalence of misinformation. It can be used to try to influence international or national public opinion, as seen with the Zelensky “videos”.

But the ubiquity and availability of these technologies also poses important challenges at the local level, especially in the growing trend of “AI calls to scam”.

Many people will have received a scam or phishing call telling us, for example, that our computer has been compromised and that we need to log in immediately, which could give the caller access to our data.

Deception is often very easy to spot, especially when the person making the call asks questions and asks for information that someone from a legitimate organization would not.

However, now imagine that the voice on the other end of the phone not a stranger but sounds exactly like a friend or loved one. This injects a whole new level of complexity and panic for the unfortunate recipient.

A recent story reported by CNN highlights an incident in which a mother received a call from an unknown number. When she answered the phone, she was her daughter. The daughter had allegedly been kidnapped and was calling his mother for ransom.

In fact, the girl was safe and sound. The scammers had made a fake of her voice.

This is not an isolated incident, and the scam has been encountered with variations, including an alleged car accident, in which the alleged victim calls his family to ask for money to get over the accident.

Old trick with new technology

This is not a new scam in and of itself. The term “virtual kidnapping scam” has been around for several years. And it can take many forms, but one of the most common is tricking victims into paying a ransom to free a loved one they believe is threatened.

The scammer tries to establish an unconditional demand and get the victim to pay the quick ransom before they find out they were tricked.

However, the rise of powerful and readily available AI technologies has upped the ante significantly and made things more personal.

It’s one thing to hang up on an anonymous caller, but it takes a lot of trust to hang up on someone who sounds like a child or partner.

There is software that can be used to identify fakes and that creates a visual representation of the audio called a spectrogram. When you’re listening to the call, it may seem impossible to distinguish it from the real person, but the voices can be differentiated when spectrograms are analyzed side by side.

At least one group has offered downloadable detection software, though such solutions may still require some technical knowledge to use.

Most people won’t be able to generate spectrograms, so what do you do when you’re not sure what you’re hearing is real? As with any other means of communication, you have to be skeptical.

If you get an unexpected call from a loved one asking for money or making requests that seem out of place, call them back or send them a text to confirm you’re really talking to them.

As AI capabilities expand, the lines between fact and fiction are becoming more blurred. And we’re not likely to be able to stop that technology. This means that people will have to become more cautious.

*Oliver Buckley is Associate Professor of Cybersecurity at the University of East Anglia (UK) and has a degree in Computing and Computer Science from Liverpool and Welsh Universities.

*This article was published on The Conversation and reproduced here under the creative commons license. Beam click here to read the original version.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.