“It was verified that in that delicious miscegenation that is the ajiaco of Cubanness, the indigenous heritage is part of the nation, together with Spaniards, Africans, Chinese, Arabs…”.

Dr. Alejandro Hartmann

All research has in its socialization the cardinal moment of its existence. When your results are published in a journal or in a book, you reach the point of your entry into the arena of discussion. It is from there that its life as a body of ideas begins. If we refer to scientific research focused on indigenous Cuba today: their faces and DNA, Ediciones Polymita S. A, 2022 (2015 pages), it is clear that this book has already become a text that provokes debates in the Cuban academy.

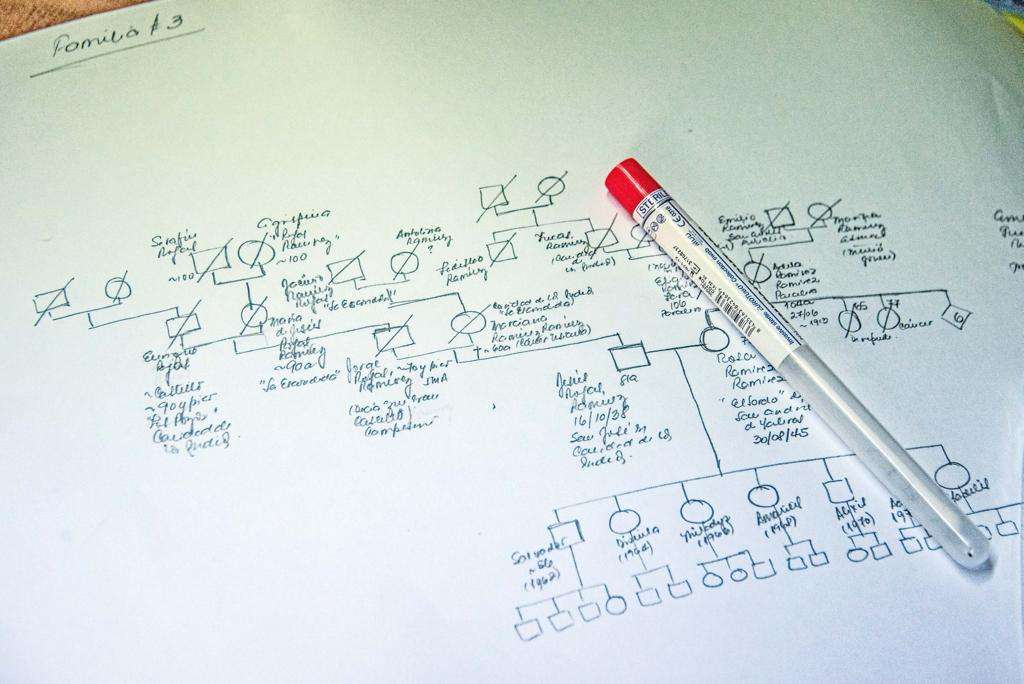

The research, carried out during five years of intense work in the field, is nourished by the contributions of a multidisciplinary team that carried out the studies, texts, production, images, as well as graphics and maps that guide the reader about the eastern Cuban region where the natives settled and their descendants still live. All those involved, with other help that cannot be cited here, carried out the enormous scientific task. Joining in this effort were the Cuban photographer Julio Larramendi, the Spanish master of the lens Héctor Garrido; Dr. Beatriz Marcheco, director of the Cuban Institute of Medical Genetics, who was in charge of the DNA tests; the renowned historian of Baracoa, Alejandro Hartmann, probably the inspiring dynamo of the project, and Enrique J. Gómez, doctor in Sociological Sciences.

The essence of the investigation lies in the thesis that the Arawaks (or Tainos) were not totally exterminated in Cuba, as is usual to read in history and basic education books. On the other hand, it states that groups of that ethnic group survived and their descendants reach the present.

The demographic and cultural catastrophe suffered by the Cuban aborigines with the conquest and colonization aroused strong controversies that have faded over time, despite the fact that some authors remained faithful to the thesis that many of these pre-Columbian inhabitants took refuge in inhospitable areas of the island and avoided death due to illness, punishment or excessive work to which they were subjected with the arrival of the colonizers.

One of those authors was Dr. Hortensia Pichardo Viñals, who in her text The origins of Jiganí, he examined the itinerary of the aborigines and found sufficient information on indigenous towns that regrouped and survived the colonial hecatomb. Previously, Juan Bautista Sagarra and Miguel Rodríguez Ferrer, in 1837 and 1847, respectively, also encouraged the thesis based on field inquiries in the eastern region of the country.

Other voices, more recent in time, such as those of the researchers Manuel Rivero de la Calle and Alejandro Hartmann, contributed new reasons. On the opposite side of the possible survival, the opinion of the wise Don Fernando Ortiz weighed heavily, who in 1939 had proclaimed: “the impact of the two cultures was terrible. One of them perished, as if struck down. The Indians are extinct. That was a very authoritative opinion and one with which it was very difficult to disagree.

The book that concerns us, the result of the homonymous research project, raises a moment of irrefutable debate. Its strongest side is in the DNA tests carried out, the body measurements, the visual evidence of the photographs and the interviews with the people investigated, who told their life stories and talked about their local cultures.

The genetic work carried out by Dr. Marcheco seems to be something difficult to doubt. The first tests had been carried out by this specialist in 2011 and then the alarms went off. The results of the tests, published in this book, showed that, on average, the individuals studied have 45.7% of their genetic information coming from European ancestors, 25.4% from African ancestors, and 20.2% from Amerindian origin. and 8.6% of Asian origin.

When comparing the tests carried out in other regions of the country, these people have more than double the percentage of genetic information of Amerindian origin. For example, Panchito, known as “El Cacique de la Montaña”, in the town of La Ranchería (Manuel Tames municipality, Guantánamo province), has 40% genetic information from Cuban aborigines.

The areas studied belong to the Manuel Tames and Yateras municipalities (both known as Caridad de los Indios), which presented the highest percentages of genes of Amerindian origin. The families of surnames Rojas and Ramírez are located among those with the highest genetic percentage from said origin. The maps show that it is these places where the largest population of descendants of the Arawak (or Taino) aborigines resides.

On the anecdotal side of the matter, the book had the absolute support of the late and prestigious Historian of Havana, Dr. Eusebio Leal Spengler, who asked Dr. Marcheco to do a DNA test on him and it was found that he had a 1 percent of aboriginal ancestry, of which Leal was very proud, as Larramendi and Garrido recently stated during the book presentation in Madrid.

The study also covered the culture and religion of these people, with very particular characteristics. In this sense, the text by sociologist Enrique J. Gómez is enlightening and is based on solid historiographical bases. This author emphasizes that the descendants of Cuban aborigines currently define themselves as “Indians of Cuba”, an idea that belongs to their identity consciousness. Their traditions are a mixture of knowledge inherited through the ancestral family route with the customs of the current times.

Just a few days ago I attended the presentation of the book in Havana, in the Palacio del Segundo Cabo building, in Old Havana, where there was a large interested audience and a group of people studied, who shared their impressions with those present. about the study, in addition to the fact that they performed two ritual songs: Sun and moon Y the mamalina.

Indigenous Cuba today… it is a comprehensive proposal, of scientific rigor and that brings new light to this old dilemma of our history. The book was edited by the experienced Silvana Garriga, with effective design by Jorge Méndez and printed by Selvi Artes Gráficas. It is financed by the Spanish Agency for International Development Cooperation (AECID) and an introductory word from Laura López García, Cultural Counselor of the Spanish Embassy in Cuba.

The images that accompany the texts are outstandingly beautiful and combine very well with the thesis of the book. The renowned filmmaker Ernesto Daranas will soon join the project, who will film a documentary on the subject.