“I love my country more than my soul.” Machiavelli.

Powerful concept, full of passion and energy, the concept of homeland. The ancients said that it was sweet to die for the country. The homeland was the land of the fathers, the sacred ground where the bones of the ancestors rested. “Sacred land of the homeland”, Fustel de Coulanges reminds us in his beautiful book on the Ancient City, the cradle of the West, classical Greece and ancient Rome. Patriotism, love of country, Fustel tells us, was for the ancients “an energetic feeling, which was for them the supreme virtue, to which all virtues were subordinated. What was more expensive for man was confused with the homeland. In her he found his good, his safety, his right, his faith, his god. By losing her, he lost everything.” There was no worse punishment for man than to be missed, banished from his homeland. In the Athens of Pericles, the beacon of our democracy, since power was concentrated in the citizens’ assembly, the harshest punishment was implied in the institution of ostracism, for which a majority decision of the citizens’ assembly meant for the accused the compulsory abandonment of the polis for ten years and consequently the loss of the homeland, that is, his land, his family, his gods, his freedom as a share in his destinies.

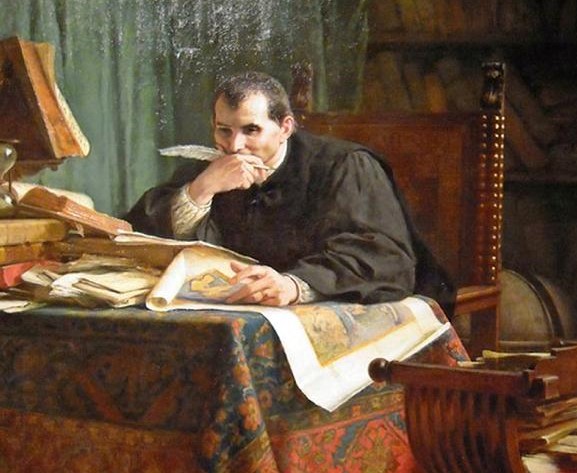

Through Renaissance humanism, whose central but not only figure is Machiavelli, the idea of the homeland coupled with the idea of the republic continues its journey, always guided by the ancient archetype, to vigorously break into the liberal-bourgeois revolutions of the last third of the twentieth century. XVIII and beginning of the XIX century. The homeland becomes a revolutionary concept, consubstantial with the destruction of the old regime, closely intertwined with the motto of the French Revolution and the ideals of freedom, equality and fraternity. Its consequence will be the yearning of the peoples for political independence and their right to sovereignly self-determine their destiny.

The homeland, the concept of homeland, first subtly and then openly, will be, more than displaced, overdetermined by the concepts of nation and nationalism, because in its aggressive version with the development of European imperialism since the mid-nineteenth century, the homeland becomes be a slogan in powerful states at the service of domination. Voltaire’s genius subtly grasped the consequences of such a situation already in his time, when he tells us in his Philosophical Dictionary: “Such is the human condition, that wishing for the greatness of our country is wishing for the decline of other countries; He who wished that his country was never bigger or smaller, richer or poorer, would be the true citizen of the universe.”

A historical example of the vicissitudes of the concept of homeland is found in the Communist Manifesto of Marx and Engels, first published in London in 1848: “The workers have no country. They can not be snatched away from what they do not possess”. Bismarck, with the vision of the statesman that he undoubtedly was, accepted the challenge and with his “social policy” incorporated the proletariat into the German homeland, and achieved the task of strengthening a nation, now powerful enough to challenge the world with its hegemony, fortunately not successful.

The country is linked to the space where we develop our lives, resulting in that space is not fixed or eternal, moving from the “small country” to the “big country”. Our great homeland today, I have no doubt, is our planet Earth. Protecting it, strengthening it, is everyone’s task, the true and only humanism of the 21st century. In short, the small countries, the nation states, must subordinate themselves to this supreme objective, since we have become, unfortunately, without many being aware of it, citizens of the world.