“Although Servando was not directly my teacher,

his example as a confident artist with firm convictions,

his love for world and national culture,

for our values and roots, their respect for the art of others,

significantly influenced my career.”

Tomas Sanchez

“Servando made one grateful to be alive every minute.”

Flavio Garciandía

Any visual artist is lonely by definition. It is about the singular situation of the human being before the canvas, the wood, the marble, the engraving plate, the camera lens, in short, whatever the support where he will create his symbols. It is the loneliness of the creator in dialogue with his preconceived ideas and images, a loneliness similar to that of a long-distance runner in athletics, alone absolutely, perhaps always with himself.

But extra-artistic reasons can increase that condition. All the reasons, those of art (including his unique work, which stood out from the others) and those of the vicissitudes of life, must have been the ones that led to the intellectual Graziella Pogolotti, who knew the artist closely and was his friend, to expressly point out that Servando Cabrera Moreno had been a “lonely walker” in the Cuban plastic scene. And he certainly was in many ways.

This May 28th we celebrate its hundred years. Servando (Havana 1923-1981) has been compared by some specialists with the greatest exponents of Cuban painting, such as Wifredo Lam, René Portocarrero, Mariano Rodríguez and Carlos Enríquez, among others, due to his enormous talent as a draughtsman and painter and a work that is impressive due to its technical quality and its thematic plurality.

He was great among the greats. Probably the artist whose work exerted a greater influence than any other on island painting from the 1970s to the present.

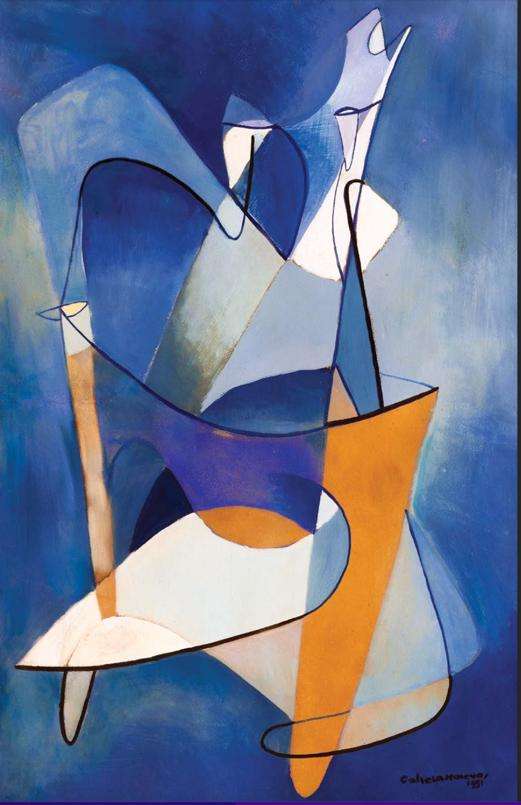

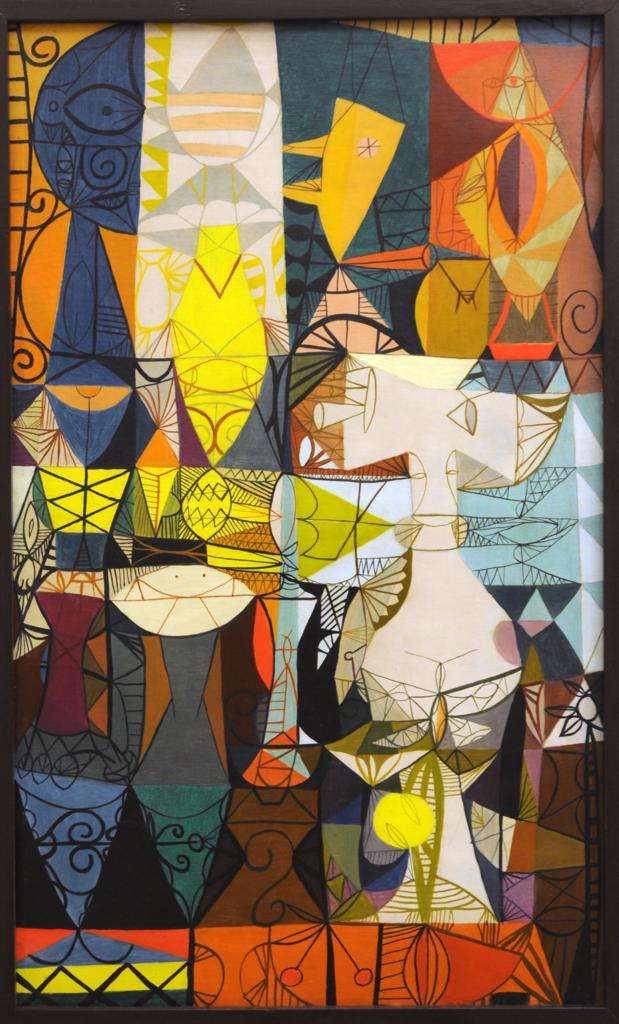

Cabrera Moreno was a creator imbued with constant experimentation and innovation. He never stayed in one place, theme or style for long. His work shifted, in rapid permutations, from the academic to the avant-garde, from expressionism to portraiture, from the influence of the first Picasso to a personal way of dealing with the subject of the body, from the geometric to abstraction, from the influences of Goya. and Italian neorealist painting to expressionism, from baroque colorism to the treatment of Havana architecture and Caribbean luminosity in a kind of very unique geometric abstraction.

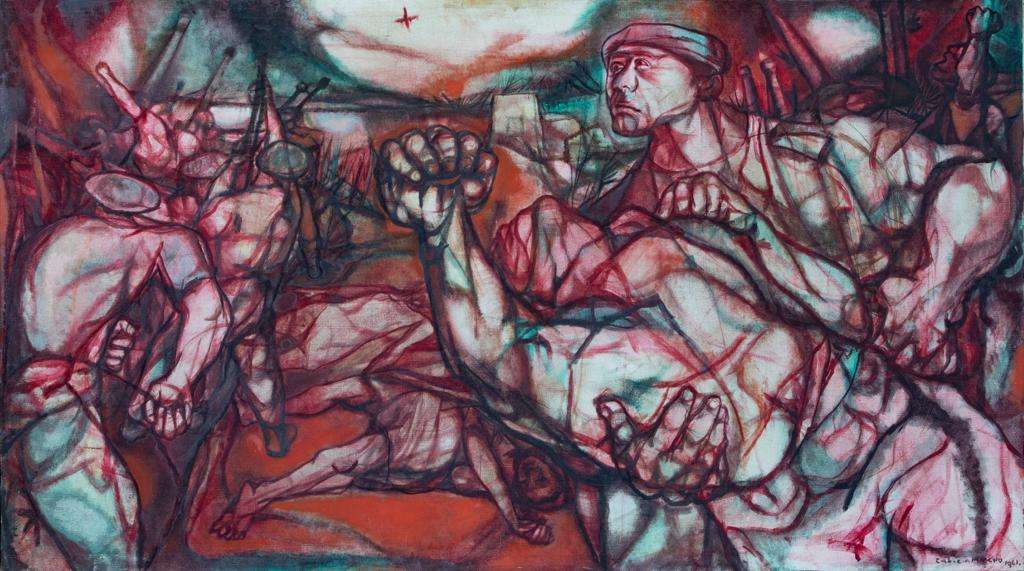

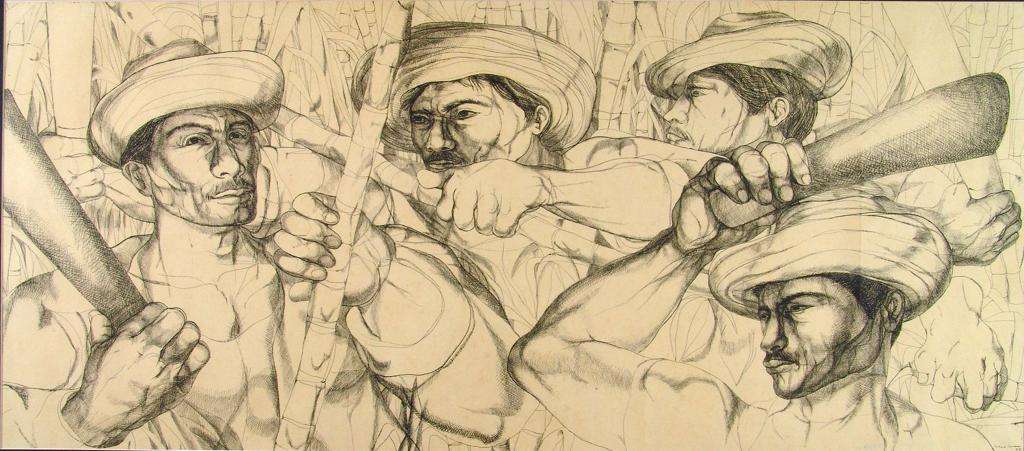

Finally, he went from grotesque figuration to the strong anthropological load that his work experienced in the first years of the Revolution and that was one of its distinctive signs from then on.

Servando traveled enough to fill the retinas of the masters of art history (Boticelli, Goya, El Greco, Miguel Ángel, Van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, De Kooning, Bacon, Tamayo, Saura, among the favourites), of the artistic currents of past eras, art events in real time, and exhibited in European galleries, all of which came together in the construction of a personal culture that greatly contributed to the growth of his work.

A lover of cinema (Federico Fellini in the first place), good literature and theater, Servando revealed himself as an animator of the Cuban cultural scene before and after the triumph of January 1, 1959. For many, he was an authentic Renaissance. That unlimited curiosity about universal culture moved him to put together a collection of pieces of popular art acquired on his numerous trips, it was one of his passions and he managed to gather a considerable set in which you can see Mexican and Spanish tableware and ceramics, altarpieces of Peruvian art and Portuguese vessels, among other valuable pieces. He turned his house into a museum with all these acquisitions.

The Revolution inspired extraordinary pictures of militiamen and macheteros. Also of other themes product of the trembling that the social changes and the contagious popular effervescence of that time produced in him. In this sense, he can be considered a master of the revolutionary epic, perhaps superior to the other artists who produced works under this influence.

Among his greatest satisfactions was teaching classes and he was very loved by his students. Flavio Garciandía, an artist-educator if there ever was one, said it this way: “Servando was a super teacher from his performance as an artist, from his rigor and dedication to Painting with a capital letter”. In 1965, when he was suspended and could no longer teach because he was homosexual, the first to suffer were his students, some of whom visited him in secret, since it was also forbidden to have relationships with him. His expulsion was an unfair and intolerant decision that made him suffer alone.

Servando had, from that moment, a difficult life due to the prevailing homophobia in the country in the turbulent sixties. His frankly assumed condition as a homosexual and his willingness to defend his sexual freedom with dignity, caused, first, his dismissal as a teacher and later a prolonged ostracism that also affected dozens of creators, playwrights and writers in the second half of that decade. (especially in the following one), when such intolerance reached the extreme of building a cruel monstrosity like the Military Production Aid Units, euphemistic name of the sadly famous UMAP, existing between 1965 and 1968, in which dozens of of young people with the purpose of “forging” them as “new men”. Fortunately, he was not confined to these camps, although his fear of such a possibility was reflected in some pieces from those years.

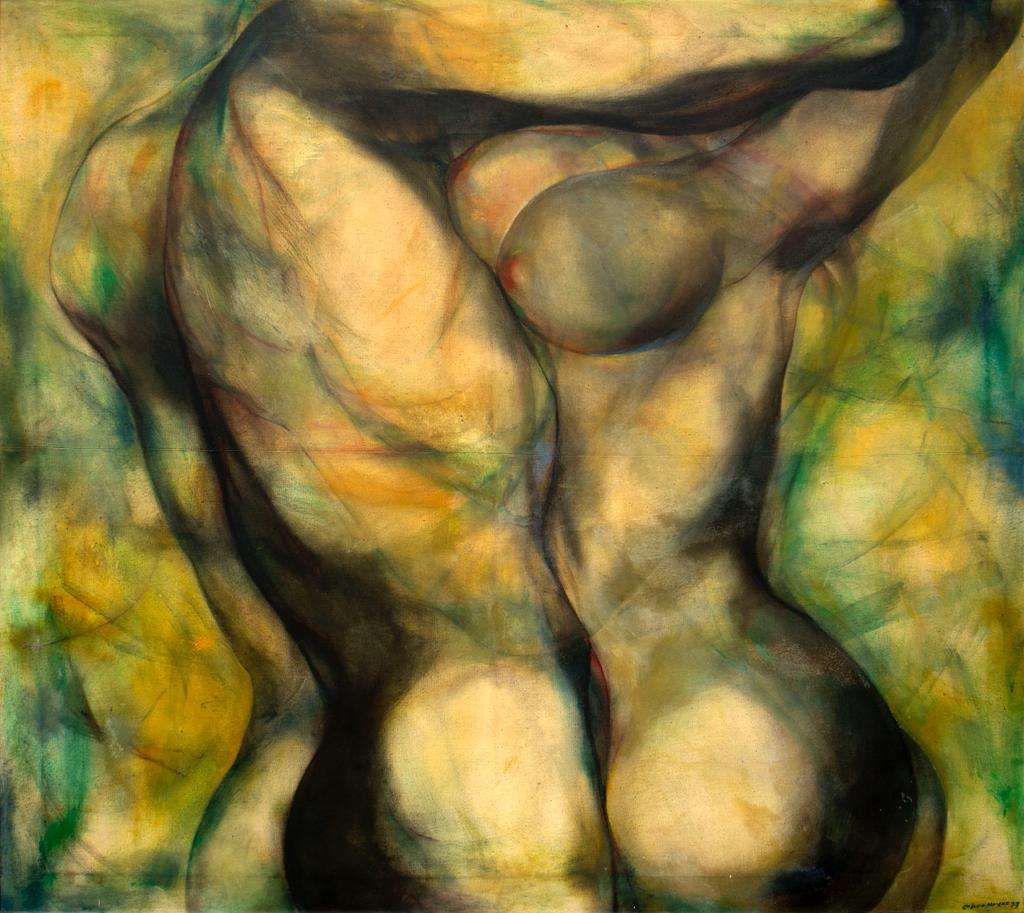

However, Servando did not stop creating art. From the seventies, already displaced from the official circuits for the reasons indicated, eroticism was his most lasting thematic station, in it he created truly impressive paintings with amatory bodies avid for pleasure, bodies without faces, which configured a very particular aesthetic.

The dynamism of the lines and the treatment of the color ranges reached levels of pictorial mastery (Servando was, in my opinion, the owner and lord of the range of blues), as well as the uninhibited and fresh way with which he presented the sexual scenes. and the erogenous zones, leaving a series of pieces that have not lost their relevance and will never lose it, given the increasing centrality of the sexual in postmodern or contemporary art. Even more so in the present with the hegemony of theories queer and the great plurality that the debates on the gender issue have reached.

Numerous critics and scholars have referred to its erotic or love theme. The curator of the National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA) Roberto Cobas, for example, expressed: “The images of his erotic painting can be as much a function of expressiveness as of a refined aestheticism. Cabrera Moreno’s painting is a great symphonic song to the human body emphasizing its monumentality”. Nelson Herrera Ysla expressed: “For Servando, love had no borders and became dynamic when eroticism appeared in the hands, arms, thighs, buttocks, indistinct torsos, metaphorically transparent in forests, jungles, inhabited by beings who love each other in total dedication. …”.

For his part, Rufo Caballero considered that: “…what we appreciate in Servando is the drive of a transsexual (or pansexual) desire that, nesting at times in one identity variant or another, wanders over fences and domains…”. And it is that the sensuality of his paintings, one could say voluptuousness, and the large format in which they were painted, produce in the viewer the reflection on Eros in full vital function. They remind us that eroticism has its own language, that it is a space that is equivalent to the rumor of insinuation and the touch of caress, that it is vertigo and dementia of the skin, unbridled reason, violence, sublimation of our ghosts, in end, hunger for life.

The pictorial work of Servando Cabrera is engraved in an imaginary frieze that only the chosen ones of art of all time reach. His work presents the credentials of the integrality of art. He was and is an indisputable master and it could be properly said that specialized criticism is just beginning to deal with his work. There is already a valid bibliography that should grow over time.

His centenary will not go unnoticed. In Panama, the NG Art Gallery inaugurated this month the exhibition from my island, curated by its technical team, the joint production of the Servando Cabrera Library Museum and the Los Carbonell Foundation. In Cuba, it will be celebrated with various exhibitions by other artists and, mainly, with a large exhibition at the National Museum of Fine Arts (MNBA), The memory of the erasedcurated by Teresa Toranzo Castillo and Rosemary Rodríguez Cruz, in the coming month of June, which will have a catalog of excellence, as well as conferences and other collateral activities.

The Library Museum that bears his name, in charge of all the homage initiatives and in coordination with other cultural institutions, has developed multiple events and exhibitions dedicated to the teacher since its inception. He did it ten years ago when he created the “Conferences dedicated to eroticism in the work of Servando Cabrera”, at the National Library of Cuba, with the participation of renowned specialists and from which the book was published. epiphany of the body, with all the presentations. He also published the splendid art book Servando Cabrera Moreno. The embrace of the senses, in 2013, is probably the most comprehensive published so far on the artist. The Los Carbonell Foundation, whose president is now in Cuba, has the largest private collection of the artist’s work, and is also participating in the Cuban tribute in an important way.