The first book that Lichi wrote, The Fifth of the beginnings (1968)—title taken from a verse by Octavio Smith—remains unpublished. Latest, my father’s novel (Mexico City, 2017), was published posthumously by Editorial Anagrama.

My brother Eliseo Alberto, Lichi, was interested in literature from a very young age, as I have said on other occasions. The three brothers read a lot: the classics that were circulating then (Rapi was born in 1949 and we, the jimaguas, in 1951): Jules Verne, Salgari and many other authors of adventure books. I remember that the first “adult” book that Rapi read was The miserable onesby Victor Hugo. He ended it crying. And it was also the last one he read. Already very ill, he asked me to take him to Mexico, where he lived. The five volumes of Ediciones Huracán had disappeared, but they had just published it—I think by Arte y Literatura—in three volumes, and I took them to them.

But Lichi had discovered Cuban literature and devoured all the titles available in my house, which were many, as you can imagine.

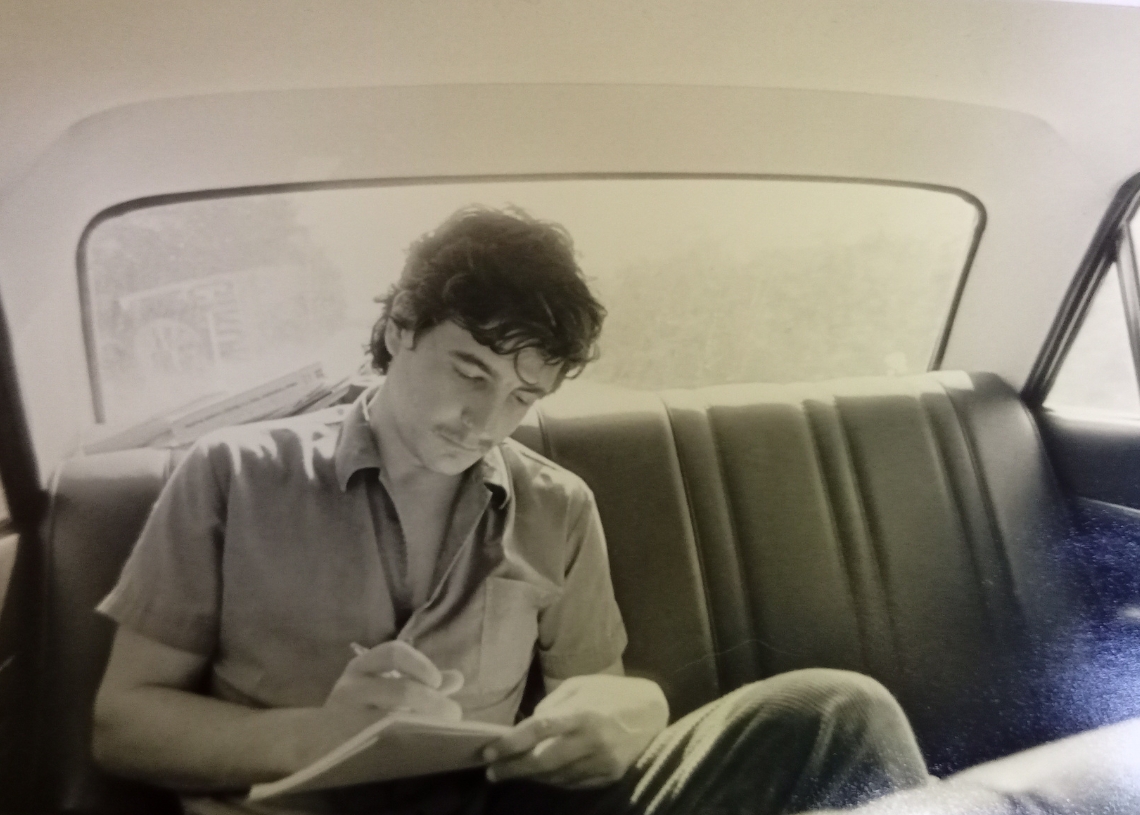

He began writing tenths that he showed to Aunt Fina; He didn’t dare show them to our father. We then lived in the Villa Berta garden house, in Arroyo Naranjo. In 1968 we moved to Vedado and began studies at the University of Havana, where Lichi graduated in Journalism. He continued writing poetry, practiced journalism, wrote a novel for young people and several film scripts. In 1989 he moved to Mexico with his family, invited by Gabriel García Márquez, and there he continued writing novels and screenplays. He completely abandoned poetry, although his prose—imaginative, solid, fluid—was always touched, in some way, by it.

The books I want to comment on are not poetry or novels. They are a kind of poetic testimonies about different moments in his life.

The Fifth of the beginnings He wrote it when we lived in Villa Berta. He was about sixteen years old. I don’t remember if he ever showed it to anyone. I did read it, and I always liked it a lot. It talks about our town, its places and characters. It is the first attempt by a young man who tells his experiences with simple and tender prose, influenced by our father’s poetry and his first readings.

Both he and I had forgotten. One day, going through files and drawers—he already lived in Mexico—I found the manuscript. I transcribed it and sent it to him. There are 145 pages. He never told me anything or showed interest in publishing it. His narrative style had changed too much and he preferred, like many authors, to leave that text forgotten. If it is read The Fifth of the beginnings and is compared to his first novel published in Mexico—with evident influence from García Márquez— Eternity finally begins on a Monday (title taken from a verse of our father), it gives the impression that they were written by two different people.

One of the places in the town that my brother describes is the ravine where a locomotive passed and the iron bridge that crossed it, known as Cambó, the name of the stop that was below. Our great-granduncle had it built, the autonomist Eliseo Giberga Gali—brother of my father’s maternal grandmother, Amelia Giberga—who lived right in front of the ravine. In our childhood, it was the only way to enter the town; Other routes existed, but they greatly extended the trip. It is still preserved.

On one of his returns to Cuba, Lichi said that when he died he wanted his ashes to be thrown from that bridge. So we did it, one rainy afternoon in September 2011. I copy below a fragment of the book, especially shocking when knowing that wish that he expressed so many years after writing it:

to a stranger

The Arroyo Naranjo Bridge, the narrow and old bridge of Arroyo Naranjo, is at the entrance to the town. Don’t be confused with the bridge that the government built recently. It’s the other one. The one from further here, a little more here.

It is known by Cambó. Learn the name well; the Cambó bridge, the Cambó stop and, even more, the sadness of Cambó. As you hear it; the sadness of Cambó. That’s what they call it in my town. He could have been called Giberga, like the great autonomist, he could have been called a thousand different things, but if that had been the case, don’t be fooled, he would have collapsed immediately. There are times when things and people can only be called one way. Nothing, that’s how it is.

But I’m moving away from your question. The bridge crosses the train line about ten meters above the rails. It will not be more than four meters wide, and its railing is made of rusty iron in a single, very old piece with a high strut and steel rivets. Long, long, don’t be scared, it will be barely eight meters. But the best thing about the bridge is its foundations. If you go down, and I recommend it, down a small staircase that you will find on the right, entering the town, you will see the immense blocks covered with moss, ferns, and hearts of lovers who have gone there to look for love. And you will find a blue and yellow booth, look at the colors!, with new names and old witchcraft. It is the booth where the train stops, where it stopped, because the passenger train has not passed for years, only the cargo train and when it does. There, the moss covers the years, the names, the dates and the foundations do not forget it. Go ahead and write your name, as if you were just another man from the town.

That is our bridge, the one you asked about, stranger. It is on the same curve and has no horizons. That’s why the town’s residents don’t go there much anymore. Here we like to see into the distance. But it’s useful for loving, I think so! The biggest thing is, and don’t laugh, that you couldn’t call the little bridge anything else. Why, by whom? Since when do you respond to the wind with that name? Until when…? I couldn’t tell you. Nobody in the town knows. Nor grandmother. Neither Severo, who is the oldest, nor the priest and Miss Francis could. But it doesn’t matter. Learn the name well and there will be no possible loss. Maybe that’s why it can only be called that: Cambó. Does it seem strange to you? I understand. But… why are you leaving, stranger? Forgive me if I have been very talkative, please don’t leave, I ask you.

If you want, don’t go down, although you will lose the best. It is a safe bridge, there is nothing to fear. It’s true that I… Look… hey, friend! You’re leaving and you haven’t even told me your name…

“You will cross the little bridge, son, like I do so many times in Uncle Eliseo’s car; like I do so many times. The little bridge… A long time ago it was made of wood… You will cross the little bridge, son, where all the men of the town, in other winds. Fresh… Among other downpours your body will cross. Among other strange greys. In another car.”

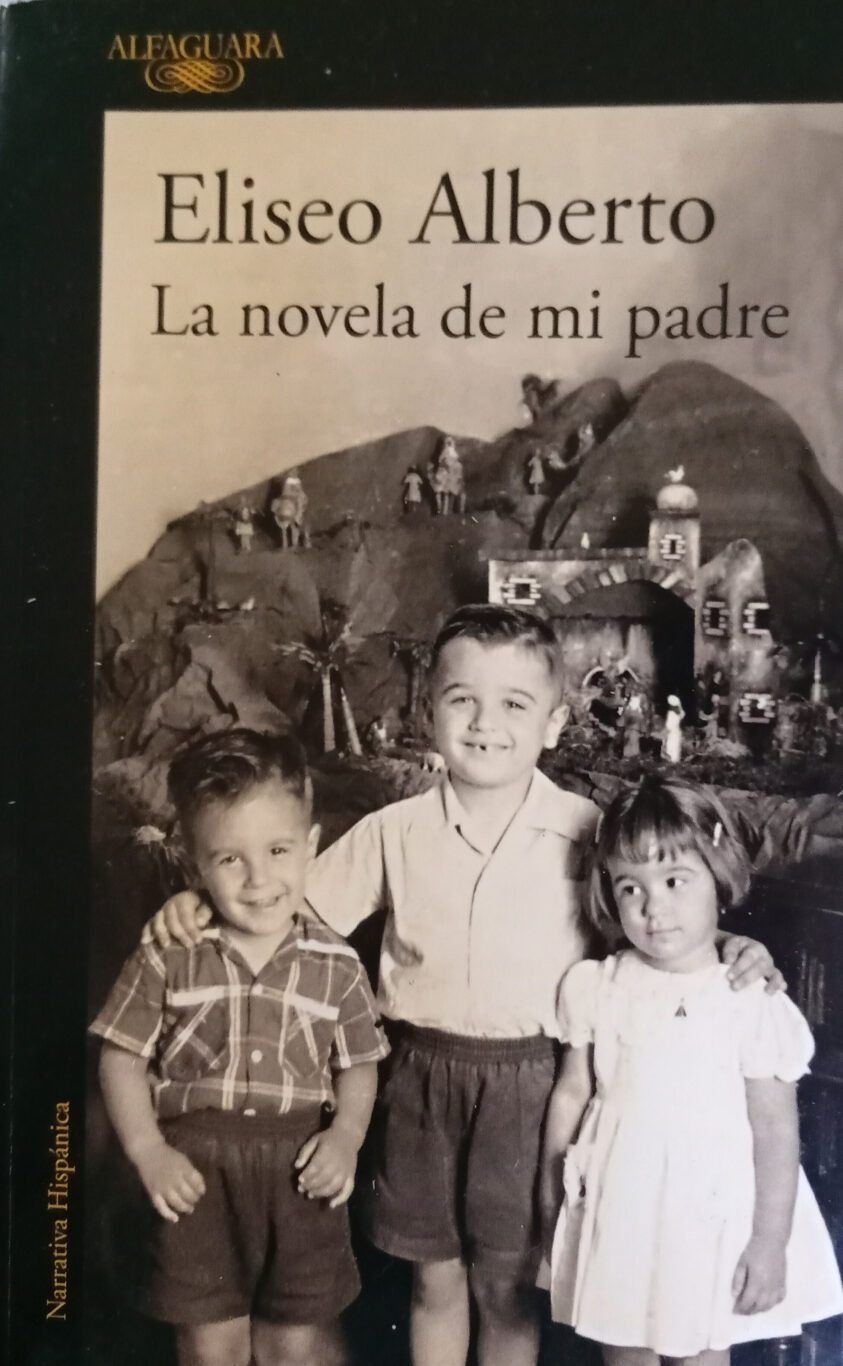

Latest

His latest book is also a set of memories, but with a very different style. After our father’s death I found, among his papers, a typewritten and handwritten document dated 1945. Its title was Sunday story and it was a novel project. As soon as I could, I sent it to my brother. It was very difficult to read, because my father’s handwriting at that time was very different from what he would have later. The main character was called Cayetano.

Lichi begins his book by narrating in detail the day our father died. The three brothers were in Mexico, since he was spending some time there. Weeks later, while I was already in Cuba with my mother, I found that document. Lichi took it as a guide to talk about that project and to reconstruct stories about our family. The first chapter deals with those two topics: the death of our father and the discovery of the manuscript.

In my father’s novelLichi intersperses several letters from our mother to our father, who was traveling in the United States in 1946. They had not yet married; They did it in 1948. The letters are very nice. Many have asked me if they are real or my brother’s invention, but they are absolutely real. I transcribed them and sent them to my two brothers.

In that book, Lichi tells anecdotes from our childhood and youth in Arroyo Naranjo, and reveals aspects of the life of our father and his family that had never been made known before, such as the relationship between his grandmother, Amelia Giberga, and his father, Constante de Diego. I didn’t like him addressing such cumbersome and sad topics, but he understood—and he was right—that they help us understand our father’s personality.

It is a very well written book. His daughter found it on Lichi’s computer with the word “End”, although perhaps he was not able to make those revisions that he always made. It is an extremely moving and warm text.

Both books, the first and the last, are important testimonies of his life and that of our father and family.