“The sun of Venezuela rises in the Essequibo!” reads part of the Venezuelan military salute, but the presence of that State in this region is non-existent. Many Venezuelan immigrants live in the “green house”, a huge building abandoned by a Chinese company in Port Kaituma

“They insist that this is Venezuela, but it is Guyana”: Kimtse Kimo Castello was born in Port Kaituma, a small town in the disputed Essequibo region. But this hairdresser has no doubt about his name: “I always felt Guyanese”

That’s how he feels, that’s how he reaffirmed it in his education. Kimtse speaks English, the official language of the Essequibo, a 160,000 km2 region administered by Guyana, although its sovereignty has been in dispute with Venezuela for more than a century.

125,000 of the 800,000 inhabitants of this former English colony live here.

“The sun of Venezuela rises in the Essequibo!” reads part of the Venezuelan military salute, but the presence of that State in this region is non-existent.

Guyana defends a limit established in 1899 by an arbitration court in Paris, while Venezuela claims the Geneva Agreement, signed in 1966 with the United Kingdom before Guyanese independence, which established the basis for a negotiated solution and ignored the previous treaty.

But the Guyanese government is promoting a process in the International Court of Justice (ICJ) to ratify the current borders and put an end to the dispute.

The Essequibo is “100% Guyana,” the president of this small country that borders Venezuela, Brazil and Suriname tells AFP. “We are very clear where our borders are.”

Irony

The government of President Nicolás Maduro defends its request on the region and rejects the process in the ICJ. The slogan “The sun of Venezuela is born in the Essequibo” is repeated in schools and accompanies official documents.

In September, Maduro published photos of Kaieteur Falls, Guyana’s main attraction, which lies in the disputed region, along with a map of Venezuela that also included that area.

Guyanese responded with protest and demanded Facebook and Twitter to remove these “illegal and offensive posts”.

View of Kaieteur Falls, in the Potaro-Siparuni region of Guyana, on September 24, 2022 Photo by Patrick Fort | AFP

“This is Guyana, we have always spoken English,” says Andrew Bailey, a 33-year-old mechanic in Port Kaituma, a town of about 3,000 people. He believes that the insistence on claiming sovereignty responds to the gigantic oil reserves found in disputed waters.

“I have never felt Venezuelan,” Kimtse insisted. “We are friendly people, people who welcome anyone in the area. That is why you see so many Venezuelans, “emphasized this hairdresser.

Between 25,000 and 30,000 Venezuelan immigrants, according to the UN and the authorities respectively, fled the crisis in their country to try their luck in Guyana. Several thousand live in the Essequibo.

It is a kind of irony of history because until before the crisis, the Guyanese, who were among the poorest on the planet, were the ones who emigrated to Venezuela. Even those born in the Essequibo received nationality.

Paul Small (52) has, for example, both nationalities: he lived in Venezuela as a child and returned to his native country with his family to work as a painter, laborer, and janitor. “There is work and the money yields more,” he maintains.

abuses

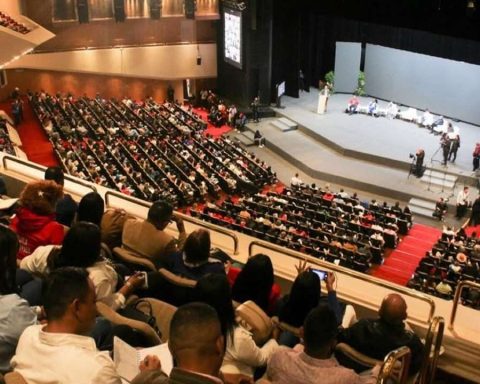

Many Venezuelan immigrants live in the “green house”, a huge building abandoned by a Chinese company in Port Kaituma.

Anneris Valenzuela, 23, left Tucupita (Delta Amacuro, east) with her husband and three children. “We had nothing. We had no way to support the children. It became easier for us to go to Guyana », she says.

Her husband works as a day laborer where he can get it. “Life is better than in Venezuela, but quite hard”: there is no electricity and the water comes intermittently. Some rely on the rain they collect in cans, pots and plastic containers.

The “green house” occupied by irregular inhabitants in Port Kaituma, Guyana, on September 22, 2022 Patrick Fort | AFP

Alexis Zapata, 47, lives with seven members of his family in two rooms in the “green house,” where only hammocks hang. “We get ready to eat every day, even if we don’t work all the time,” he told AFP.

He arrived in Port Kaituma in 2021, also from Delta Amacuro, one of the poorest regions in Venezuela and the scene of numerous tragedies of migrants drowning in the ocean trying to reach Trinidad and Tobago.

Alexis chose Guyana precisely because there were no boats to take, smugglers to pay, or police to avoid.

He works unloading ships in the town’s port. They pay him a percentage of the value of the merchandise, although he receives “less than the Guyanese,” who take advantage of his need and his poor English.

Earn between 5 and 15 dollar cents with each download: “Better than in Venezuela,” he says.

Post Views: two