On April 9, 1948, Gloria Gaitán, the 10-year-old daughter of Jorge Eliécer Gaitán, looked out the window of her house at the red sky of Bogotá, a city in flames due to the assassination of her father, presidential candidate and the most popular of the moment

“I was convinced that my father was not dying, but was going to heaven, raised by angels with red flags,” says Gloria Gaitán, 85 years old, sitting in front of said house.

Today, 75 years later, “I still think the same thing,” he says.

At 1:00 pm that rainy Friday in Bogotá, Jorge Eliécer Gaitán was shot three times as he was leaving his office. Half an hour later he died in a nearby clinic.

His wife, Amparo Jaramillo, stole the body from the hospital because they wouldn’t let her take it out: she extracted it through the garbage door and transferred it, wrapped in sheets and newspapers, to that same house in what is known in Colombia as a “fox”, a wheelbarrow pulled by a horse.

They kept a wake for him and, after a heated discussion that included the then president, the conservative Mariano Ospina, they buried him in the living room of the house.

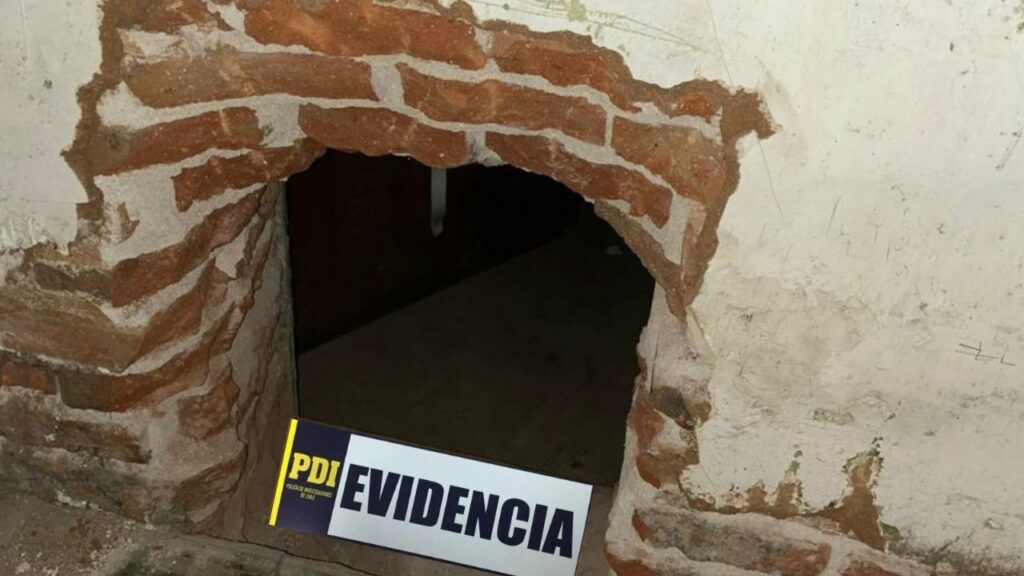

It was there until 1988, when it was transferred to the patio, where today the remains lie surrounded by a majestic brick building that was built to be a museum of the life and political work of Gaitán, but which was never finished and was abandoned for the last few years. 20 years.

When they killed him, Gaitán was already a symbol for Colombians. In a country dominated by political elites, the charismatic and eloquent politician promised to shake up the system. At the height of the Cold War, critics of him and US officials feared he was a communist bishop.

Those who dreamed of getting out of exclusion through him lost all hope as soon as they found out about the assassination of the then presidential candidate and favorite for the 1949 elections. The assassination was a very hard blow to a fragile democracy.

The 75th anniversary this time will be different. This April 9, the assassination is commemorated on Easter Sunday, an important date for this largely Catholic country. And in the presidency there is a politician who tries to pick up the legacy of Gaitán: Gustavo Petro, a standard-bearer like him for social justice and the first left-wing president to confront the elites.

“There are energetic forces that operate,” says Gloria Gaitán. “The fact that the 9th falls on Easter Sunday and Petro is in power is no coincidence,” she believes.

Petro appointed María Gaitán-Valencia, daughter of Gloria and granddaughter of Gaitán, as the director of the Historical Memory Center, the state body in charge of recounting the past.

“Today the victim will have in his hands the historical truth of Colombia,” Petro said in his appointment. “Not the victimizer.”

It is the first time in 30 years that the Gaitán family is in tune with the government.

“On Sunday, with the presence of Petro, we are going to clean up this place of 20 years of memoricide,” says Gloria, referring to the theory that “governments, the oligarchy and academics have refused to remember and understand” the popular leader.

María adds: “The time has come for the people, for the national country and not the political country, to look into each other’s eyes and tell their own story.”

Among many of Gaitán’s famous phrases, the most remembered, because it was premonitory, is this: “The oligarchy does not kill me because it knows that if it does, the country will overturn and the waters will take fifty years to return to their normal level.”

Gaitán’s assassination in 1948 occurred during the Ninth Pan-American Conference in Bogotá, a summit that included US Secretary of State George Marshall, among other figures.

A young Fidel Castro, an admirer of Gaitán, was attending a student congress in the capital those same days.

That Friday, April 9, is known above all as the “Bogotazo”, but also the “Colombianazo”, because the riots in protest against the assassination not only took over the capital, but also various regions of the country.

President Ospina declared a state of siege, the army was mobilized for the repression and liquor stores, stores and banks were looted. Snipers from both sides were reported. Even the priests fired from the churches. An estimated 4,000 people died that day alone.

Although the violence came from before, after the Bogotazo it intensified. In 1953 there was a coup that did not achieve peace either. Then, in 1958, a pact for alternation of power was signed between the two main parties that convinced thousands of citizens that arms were the only way to have a voice. In the 1960s, six guerrillas emerged.

Today, when Petro promises “total peace”, Colombia still suffers from the remnants of that political violence that began in the 1940s.

And the murder of Gaitán continues in impunity: the murderer, Juan Roa Sierra, was lynched that same day and his body was left at the door of the presidential palace. Theories about the mastermind include President Ospina, oil companies, the communist party and the United States, the version defended by the family.

“I have no doubt that it was the CIA,” says Gloria Gaitán today.

Amid the chaos of April 9, Amparo Jaramillo said he would not bury Gaitán’s body until the conservative Ospina government fell. She decided to leave him, as well as his murderer, lying in front of the palace; she also buried him in the Plaza de Bolívar.

Ultimately, the living room in the house was the only viable option.

In 1960, the body was exhumed as part of the judicial investigation. Then, in 1988, they moved it to the patio and buried it with earth brought from each municipality in the country.

The most important Colombian architect, Rogelio Salmona, built an Exploratory there that would serve as a museum and a center for thought and deliberation on the leader’s legacy.

“It’s a space for heroes,” says Gloria, “to generate a cultural change that goes beyond participatory democracy and leads us to direct democracy, just like my dad wanted.”

But 20 years ago the project was abandoned: one of the most beautiful buildings in Colombian architecture was half finished.

Gloria blames “memoricide promoted by the oligarchy”, represented by presidents like Álvaro Uribe and Juan Manuel Santos.

But now that Petro has risen to power, Gloria, who has dedicated her life to “continuing the fight” for her father, is confident that the Exploratorium will finally end.

Just as Gaitán’s remains and mausoleum have been in constant dispute for 75 years, his memory has been the subject of constant discussion.

Gloria accuses a “bourgeois, anchored in the 20th century” academy of refusing to understand Gaitanista thought, “which is from the 21st century.”

“Some want to remember Gaitán and not the revolts, and others want to remember the revolts and not Gaitán,” says Herbert Braun, writer of one of the most cited books —although discredited by the family— on April 9.

The historian assures that “understanding the magnitude of the episode continues to be very difficult, either because some do not want to look back or because we do not know who was involved, what elements were at stake or what the consequences really were.”

In the absence of an official story about Gaitán, Colombians seem to stick to the mystical tale. Something that his daughter celebrates, while the academics reproach him.

“The problem with myths is that they overshadow history and historical research,” says Olga González, a sociologist and historian at the Sorbonne University in Paris.

“It’s not that there’s nothing written about him, but the majority is focused on his murder and the trauma of the Bogotazo; it’s limited to a year and a half, for a life of 50 years.”

“You tell people that Gaitán was racist in the ’46 campaign, that he had alliances with conservatives, that the Gaitánistas were violent and he did not censor violence, and they do not believe you,” he says.

The Gaitán myth remains unresolved. The archives of his newspaper, Jornada, remain restricted. The Truth Commission, the body that wrote the history of the armed conflict between the State and the FARC guerrilla, devoted just a few pages to the liberal leader.

And, if history is not resolved, much less is the violence and inequality that made Gaitán a popular idol.

The memory of the caudillo is like his mausoleum: pending resolution.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.