March 18, 2023, 8:46 AM

March 18, 2023, 8:46 AM

Not many Mexicans know that what today houses a large water park in their country was during World War II a concentration camp for Japanese who then lived in Aztec lands.

This is the old Temixco hacienda, located about 100 km south of Mexico City, where some 600 people were detained who could thus be controlled by the Mexican authorities at the express request of the United States.

pink uranus It was one of the inhabitants of the field. She arrived when she was only 6 years old with Yashiro, her Japanese father; María, her Mexican mother; and her two brothers. Today, with 87 years, He still remembers when the family received the news that they had to leave their home in the Mexican state of Veracruz.

“My parents were very sad, but he always said that as soon as the war was over we were going to return. And with that idea we came,” he tells BBC Mundo as he walks through the old hacienda that became his home for about three years. .

The one in Temixco was not a Nazi extermination camp or one of the internment camps in which the US confined thousands of citizens of Japanese origin at that time and from which they were totally prohibited from leaving.

“The entrance to Temixco, on the other hand, was guarded by members of the army, but let’s say that it was lax surveillance. Here they could go out to the vicinity after reporting, although to move out of the city they had to request and obtain a permit first,” he told her. explains to BBC Mundo Sergio Hernandez, Mexican historian expert in Japanese migration in the country.

Despite everything, the memory of many of these people of Japanese origin who arrived in Temixco as adults, forced to leave behind their lives and years of integration in other areas of Mexico, is of absolute sadness at the clear injustice committed against them.

forced to concentrate

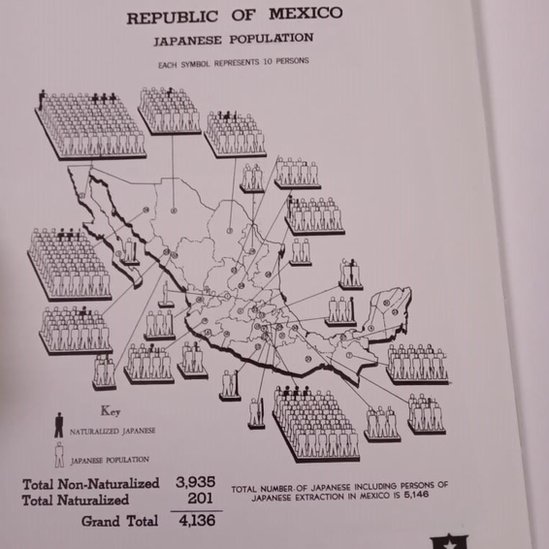

Following Japan’s attack on the US base at Pearl Harbor in late 1941, Washington began rounding up Japanese migrants for close surveillance and asked other countries in the region to follow suit.

According to Hernández, “the Mexican government accepted the pressure from the North American government to transfer them, but unlike other Latin American countries, I decidedió do not send them to US fields but concentrated them in Mexico itself”.

The main US interest was to keep them away from the area near their border, considering that their presence there could pose a danger to their security and a risk of espionage.

Fearful that they might end up being taken to US camps, the Japanese in Mexico had no choice but to leave their homes and businesses and agree to move to Mexico City and Guadalajara on their own, as required. the Mexican authorities.

Their compatriots who already lived in these cities organized themselves in the kyoei-kai (Mutual Aid Committee) to receive them and support the hundreds of families that were arriving. The address where they would stay while the war lasted it was registered, one by one, by the Mexican Ministry of the Interior.

But after abandoning their lives in other parts of the country, many of them did not have the resources to survive in their new destinations, so it became necessary to find a place where they could support themselves.

In the municipality of Tala, in Jalisco, a field was set up on a ranch for those who arrived in Guadalajara. For his part, with money provided by the Embassy of Japan in Mexico, the kyoei-kai he acquired a much larger former hacienda (about 250 hectares) in Temixco for those relocated to Mexico City.

It was an old sugar ranch that, given the weather and the presence of a river, offered optimal conditions for growing products such as rice and vegetables.

“The presence of water was the most important thing to choose this place, because most of those who arrived were previously engaged in farming in northern Mexico, so they could have sufficient cultivation,” he tells BBC Mundo Tooru Ebisawa, Mexican of Japanese descent who has spent years documenting and researching this part of history.

Memories from eight decades ago

Walking with Mrs. Rosa Urano through the Temixco ex-hacienda is like moving back in time thanks to her clear memories. Without hesitating for a moment, she points to the area where the kitchens were, the stream where her mother washed the pots, or the area of small wooden bedrooms that the camp inhabitants themselves built.

Remember that the whole family slept on a mat on the dais. They did not have a kitchen, since they all ate in the communal dining room attended by their mother and the rest of the women on the hacienda.

“My mom used to tell us that we had to get to the kitchen early so that we could have a little piece of meat at noon, because it was rationed. If we arrived later, it was already pure broth with vegetables “, she recounts.

Children like her attended the public school located on the outskirts of the camp. They also had the option of attending the one that was installed in Temixco and the one that was taught in Japanese.

The men, for their part, were in charge of working in the fields from early in the morning in long working days during which they grew food for their consumption and for sale, and for which they were paid four pesos a week (US$0.21 at current exchange rates).

Urano says that this money was used by his family to buy soap to bathe with. In order to buy some clothes, his mother sold raspados de frutas (ice slushies) on the outskirts of the field.

Protests over working conditions

These working conditions and the coordination of who was chosen by the kyoei-kai as administrator of the camp, Takugoro Shibayama (who lived with his family in a stone house in different conditions than the small dormitories of the rest), motivated the protests of some of the inmates.

One of them was Seiki Hiromoto, who worked as a doctor at the ranch and where he married a young Japanese woman.

according to his grandson Kenji Hiromoto, who has been studying his family’s history for years, his confrontation with the administrator earned him being reported to the Mexican authorities and sent to the Perote prison camp in Veracruz for six months. Italians and Germans were also concentrated there under much stricter conditions and surveillance.

“He jumped over the fence of the farm at hours that were no longer allowed to cure the locals of the town, who paid him with chickens or eggs that served him to complete what they sowed in the field, because there was not enough for everyone. Until They surprised him and falsely accused him of being a spy,” he told BBC Mundo.

“I can say that my family did not have a good taste of what they experienced here: there was exploitation, injustice and privileges on the part of those who ran the farm, curfew, food rationing… My grandmother told me that they had suffered enough,” he adds based on the conversations he had with his grandparents and his grandfather’s brothers who lived in Temixco.

“In the interviews we did, there were different versions about the farm administrator. His function was to bring order and it is said that he was very strict, so those who were sent to Perote did not like him,” says Ebisawa.

No apologies from the authorities

In Rosa Urano’s childhood memories, as is to be expected, her experience in Temixco was different. “I can’t say that they were sad years, because I had someone to play with and I didn’t give importance to other things,” she says.

Of course, the opinion of his parents was very different. “When we asked my dad if he had been happy here, he always said no, that He came from Japan to suffer here. But I didn’t want to go back there either.”

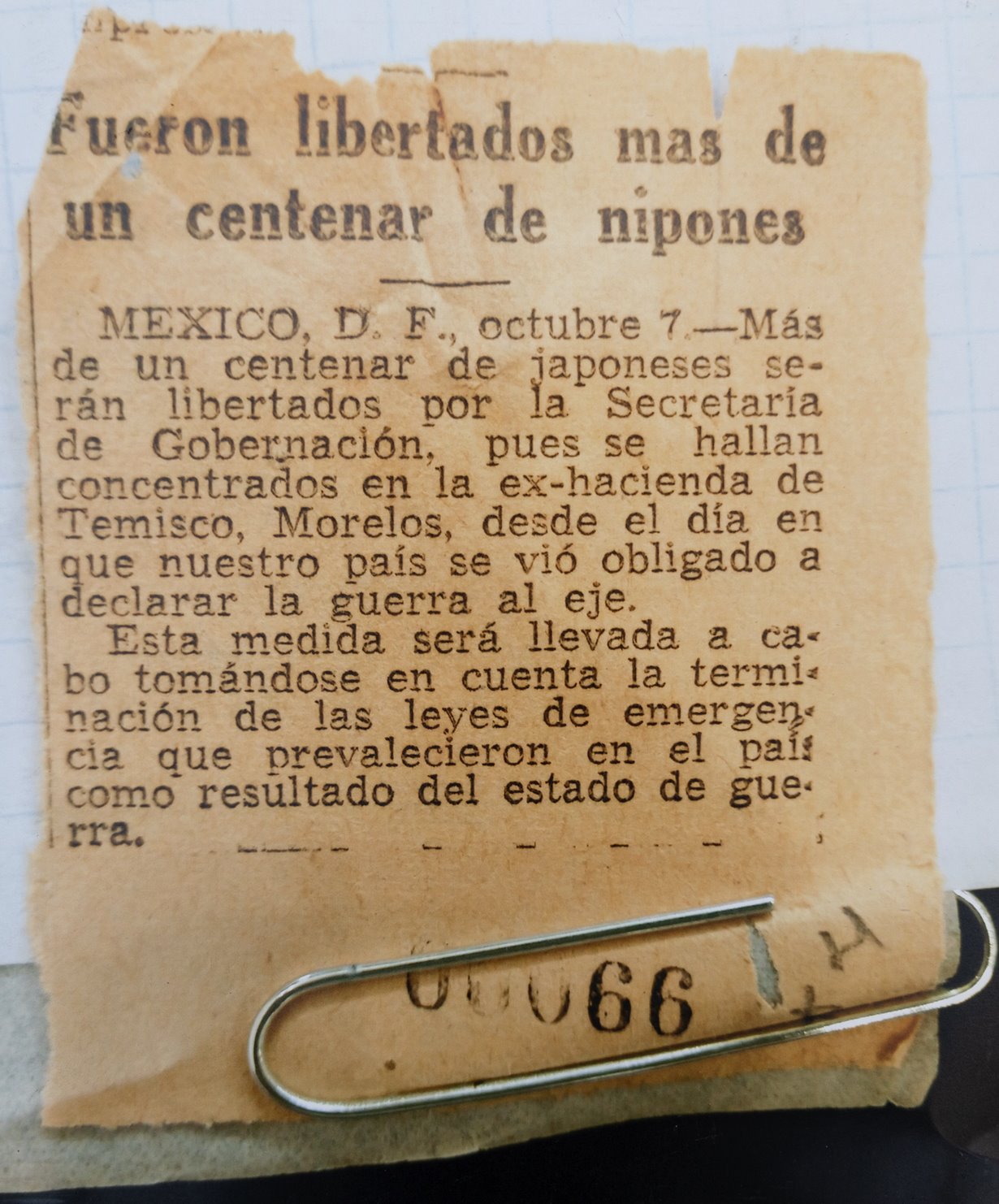

When the war ended, the Japanese in Temixco were once again free to go where they wanted. Many, like Urano’s family, decided to stay in the area after years away from what had been their home before the conflict.

The grandfather and father of Fernando Alvarez, current co-owner of the land, they bought the farm in 1949 to dedicate themselves to rice processing and, two decades later, to become the current theme park. But his connection with the Japanese community is always present.

“Many years ago, three Japanese, two men and one woman, came here. They asked me if they could come in because they had lived here. And they turned out to be members of the Shibayama family, they were his children” recalls Álvarez in conversation with BBC Mundo.

The historian Hernández especially criticizes the persecution suffered in Mexico not only by the Japanese, but also by those around them.

“The wives of some Japanese, who were Mexican, also suffered a terrible violation of their rights, forcing them to concentrate here. And it also affected Japanese who were already naturalized Mexicans. It was clearly racial persecution,” ensures.

For this reason, the expert defends that the Mexican government owes them “an apology” these people. However, many of those affected “do not feel aggrieved when compared to those who lived in the US concentration camps. Rather, they are grateful to the Mexico that received them,” she says.

An example of this is Rosa Urano herself, for whom the decision to join the Japanese in Temixco was not something negative.

“What I do recognize is that, until now, I don’t know why they did it. Because we all had a beautiful house that stayed there, in another place. I think we should have a reason for that decision,” she reflects as she heads out of the old hacienda, leaving behind years of memories.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC News World. Download the latest version of our app and activate them so you don’t miss out on our best content.