The Sun was not Nevsky Prospect, it was the line that divided the city in two

To Mukien Sang.

Juliano Dupont was still very young when he faced his first great dilemma in life: to love a stranger or not to love.

She was beautiful, with a shyness of someone who never felt the admiration of others, who looked at her with interested eyes. Hers were green as if they reflected the forest, or as if they meowed a lonely tenderness. Her dark skin shone in the sun brighter than her distant grandmother who was trapped in a tribe just beyond the edge of the world and who left each grandchild a little gift…behind her ear.

When she captured, with her two eyes, every detail of that immense absurd monument, she walked towards Calle del Sol. He forgot about the chichiguas, the circus and the boys who played ball.

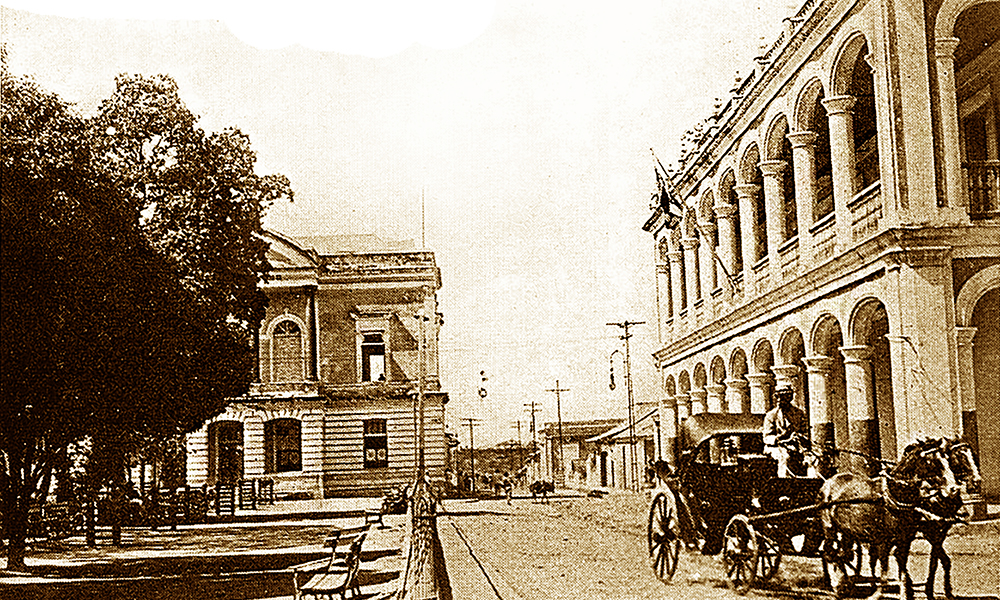

He followed her with appropriate steps, not too close and not too far, as Holmes did in so many pages of Conan Doyle. Already in the Ulises Franco Bidó, he caught up with her shadow that covered almost all the asphalt, free of cars. It was a beautiful and resplendent street with frambodian trees on both sides, which had the Sun as a beacon from the east. Almost lonely at that early hour. You couldn’t see, from there, the river in the form of a “boa cuquiá”, at the end.

General López street prevented it with its desire for a wall that was no longer vigilant since they put three forts on it, like three transparent giants that saw the mirror of its waters.

The Sun was not Gogol’s Nevsky Prospect, it was simply the line that divided the city into two halves before they crossed it, on St. Louis, to put the poor below and the rest, Town, above.

The city, now in four parts, was its own flag.

The green-eyed goddess kept stepping on her shadow and as she passed by La Altagracia Church, a bell rang frightened her, but she collected her shock in a sigh and greeted the coachman who was waiting for the five rosaries from his confessional passenger. Columbus had not yet set foot in front of the Golden Fish no matter how much the pirate Dionisio insisted.

A little further down they began to mingle with young people in white shirts, ties, hurried, combed with Palmolive Vaseline, perfumed with Florida water from Murray and Laman, and with the smile of someone who had changed the habit of carrying water on a donkey for that of selling Bazaar shoes, checkered shirts, underpants and everything that was sold in stores. Nobody noticed The Goddess, the worry of arriving on time and with shiny shoes, scared any lost Cupid at that hour, even if he was motorized.

Cars and carts rolled on the threshold of the era with a piece that vanished and another that gained strength until it dominated the road and twisted it in the opposite direction.

Dupont knew, that smell of horse shit and sour beer, wafting through the gutters, couldn’t last. If it wasn’t Gobaira, someone else would take over, even if it cost the people their vote.

Upon arriving at Sánchez she heard a sound of rain and entered the Santiago Bookstore. The clerk, with a red apron and a rehearsed smile, asked her whether with potatoes or plantains, but the smell of turpentine coming from Yoryi’s workshop drove her away while the clicking of the underwoods on the second floor faded. She crossed the street until she faced the columns of the Parthenon at the corner of San Luis and there she came face to face with Juliano who only managed to say a very short telegram:

-Hello. Stop… and as if a 5-chele stamp were stuck in his mouth, he fell silent. She continued at the rate of Better Better Better Better Probably watched by some brecher accountant of the bank, through some window.

The donkeys and passers-by intertwined some in the direction of the Market, others towards La Elegancia by José Gutiérrez, few to the Fenelón store that did not sell “guaimamas” or “caisapollos” or perhaps to the Tamboril stop where Fin and Chencho were waiting. fill their Austins to repeat the routine that united the two towns.

The gombadres and the barsanos prepared their foaming tisanes amid rolls of cloth, ready to sell even a turban to the first to enter their palaces. But The Goddess was not shopping.

He quickened his pace in front of the Normal pharmacy, which I always confuse with La Nueva, thanks Miguel Ángel. He couldn’t stand the smell of the hospital, he preferred the tobacco that rose up Duarte and erased the smell of the horses and that of Daniel Espinal.

In the Market the numbers and figures rained down that promised sure prizes, although less than the adventures that Eduardo sold at the central door, like a jealous guardian of the treasure of lettuce, radishes, eggplants, oregano, molondrones, eggs, lemons and thousands of fantastic tales. that he knew by heart. Dressed elegantly in a black T-shirt with sleeves adjusted to his muscles, flared pants, black high-heeled shoes and a pride that he stamped in a Mexican magazine of strengths, and that he built by lifting cans filled with cement in Pueblo Nuevo. He gave her a smile, convinced that he was the reincarnation of Spartacus and she reciprocated with hers as the goddess with which Julian had crowned her.

A desperate donkey entered the Reguero de Chom García with its harness almost undone, followed by a five-legged donkey. She turned around at the end of the patio and they both came out together, one on top of the other without breaking a single cup. After a while, now with their four legs each, they were recovered by their owners as if they came out of a chapter of the Macario and Felipa comedy painting.

El Rubio, who looked like the twin of San Luis, was selling small packages and newspapers on the north wall of the Iglesia del Carmen.

The tumult, both pedestrians and conchos, completely subsided as they approached the Chinese from March 30 who had nothing to do with that story.

The detour to the north marked another pace to the Hotel Oriente, also Chinese without history.

She went in, asked for an apple, as fresh as any month and juicier than Eva’s.

A gray kennel came to a halt. They knocked down two young men with greasy hair and red shirts who were pushed inside, with all their shadows, through the east door of the Governor’s Office.

She stopped, always stepping on hers that was getting smaller and smaller. Dupont, now in the park, continued to follow her, parallel to it, as if it were a premonition that indicated to him that geometric law of the impossibility of coming together.

Peña’s posters on the corner did not stop her or scare her, perhaps because the mixture of apple with the fragrance of the bread was beginning to intoxicate her and because she never paid attention to a little paper doll.

The shadow fell on her like a shaft of light from a UFO and she was trapped below her, motionless. That’s when she blew the fire department whistle.

Suddenly, she took off her shoes and began to run, perhaps so as not to see the Cultural Center, the Santiago Club, the Tomás Museum, or the San Antonio Church, much less feel the “vajo” of rotten cabbage from the Hospedaje. He also ran in parallel, dodging marchantas, yucca cerones carriers, sacks of rice from Valerio’s stores, pimps, leathers, drunken piglets from a carnival that scared children with pure bladders in Plaza Valerio, and even Memé, who kept the elegance of when it was forbidden to walk around in shirt sleeves, twenty years ago.

She reached the river, threw her shoes on the shore, undressed, and jumped into the Yaque current.

Stepping on her clothes in bewilderment, he saw his goddess, now a mermaid, swim down the river. Life is a boat, Calderón…