The voices repeat themselves, intertwine. In each story, the “doctor” name appears as if he were part of the family. On Sunday, October 19, before dawn, hundreds of people gathered in Plaza La Candelaria, in the center of Caracas, to celebrate the canonization of the first two Venezuelan saints.

Author: Gaby Mesones Rojo

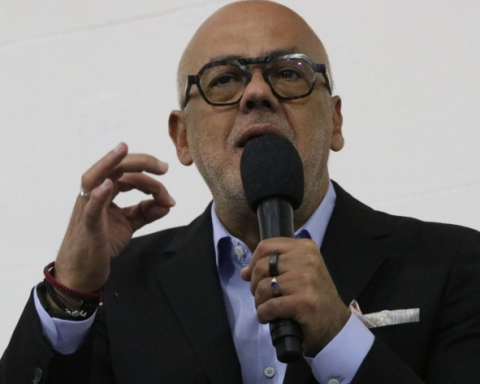

When we talk about miracles, in Venezuela we start with a love story. “My son was born at 26 weeks of pregnancy. He is alive thanks to the doctor. What I love most in my life, I have here with me thanks to him,” says Yorgelis López, a 27-year-old woman from Caracas, while her son Yeffrey smiles at her side with a mouth full of ice cream. A few meters away, another devotee remembers: “A roof fell on my wife. It collapsed in a matter of seconds, and I could only watch. That was 34 years ago. Every day I thank José Gregorio Hernández.”

The voices repeat themselves, intertwine. In each story, the “doctor” name appears as if he were part of the family.

Valeria Pedicini

On Sunday, October 19, before dawn, hundreds of people gathered in Plaza La Candelaria, in the center of Caracas, to celebrate the canonization of the first two Venezuelan saints: José Gregorio Hernández and Mother Carmen Rendiles. It was a quiet day, marked by songs, prayers and emotional testimonies broadcast over loudspeakers, hot chocolate and fireworks. The church remained open while the canonization mass led by Pope Leo XIV was screened live from Rome with Spanish translation.

José Gregorio Hernández is one of the most emblematic figures of Venezuelan Catholicism. Born in 1864 in Isnotú, Trujillo, he stood out as a doctor, scientist and university professor. His life was marked by free care for those most in need, which earned him the nickname “the doctor of the poor.” He died in 1919 and, thanks to the deep popular devotion he aroused, his beatification process began in 1949 and extended for more than seven decades until his canonization.

Valeria Pedicini

For Gloria Marcano, one of the architects who was part of the team restoring the Nuestra Señora de la Candelaria Sanctuary in 2016, where the remains of José Gregorio Hernández are located, the doctor was always a saint: “My entire family was devout, and I grew up feeling that he was just another saint. I grew up listening to stories, many of them, but I was surprised when I found out that he really was not a saint. For me, being here today is like seeing the man reach the moon, that’s how important this is.”

*Read also: Saints for Venezuela: José Gregorio Hernández and Carmen Rendiles canonized

Jessica has been a nurse for 16 years. “I have been devout since I started studying nursing, because I saw how many patients and their families prayed to her. Now my three daughters, who are also nurses, pray to her when things get difficult,” she says, with a rosary in her hands. She has worked in hospitals in Caracas, Zulia and Lara, and also as a private caregiver. “There are many difficult moments, because we all know how hospitals have suffered. For me, José Gregorio Hernández represents the importance of health, of taking care of ourselves and of having good and prepared people. Seeing his canonization today gives me hope that we know what things are important and we strive to improve. It is not in vain that we celebrate someone who helped so much in health, and another person who did the same in education.”

Valeria Pedicini

Bekys arrived in Caracas from Tovar three years ago, after her father’s accident. “I came because in my town there was no way to do physical therapy for the shoulder. We found a recommendation at the Military Hospital, and I think it was thanks to José Gregorio,” he says. For her, the canonization reflects what we as a society need to reinforce: “Health and education are two of the most important pillars that are most in crisis today in Venezuela. This should inspire us to grow in these aspects, to recognize that we deserve more.”

Although the devotion of many attendees in Plaza La Candelaria was directed to José Gregorio Hernández, Mother Carmen Rendiles also stands out as a discreet figure of Venezuelan religion, linked to education. She was born in Caracas in 1903, the third of nine siblings in a wealthy family. Unlike José Gregorio Hernández, she was able to live a full consecrated life, but like him, she dedicated her work to education and social service.

Valeria Pedicini

She was born without her left arm, a congenital defect that led her to be rejected by some local congregations, until the Sisters of Saint Joseph of Tarbes, of French origin, accepted her in Caracas at the age of 24. In 1965 she founded the Servants of Jesus of Venezuela, which she led until the end of her life.

Despite her disability, Mother Carmen developed skills in trades such as carpentry and painting, and always stood out for her discipline, creativity and independence. He frequently visited the schools and parish works of his congregation, and instead of giving formal classes, he preferred to talk with students and parents about the relationship between faith and daily life, inspired by his experience as a young catechist in parishes near his hometown.

Valeria Pedicini

Mother Rosa María Ríos, one of her former students and fellow congregation, describes her in statements to America Magazine as a worker without a quest for glory: “she liked to work discreetly, like yeast acts in flour” and explains that one of the importance of canonization is that the Venezuelan public will learn more about her, her life and her thoughts.

Mother Ríos considers that the educational system in Venezuela also needs “reconstruction.” According to a June 2025 education survey by the HumVenezuela coalition, nearly half of school-aged children in the country—some 3 million children and adolescents—do not regularly attend primary school, affected by food insecurity, migration and other social and economic forces, or face poor conditions in public schools, where deteriorating infrastructure and teacher shortages have been a problem. persistent.

Valeria Pedicini

The canonization ceremony not only honored two exemplary Venezuelans, but also highlighted what faith and community service can achieve: inspiring hope, recognizing human dignity, and reminding us that every small act of solidarity is a miracle in itself, especially in times of crisis.

Valeria Pedicini

Post Views: 237