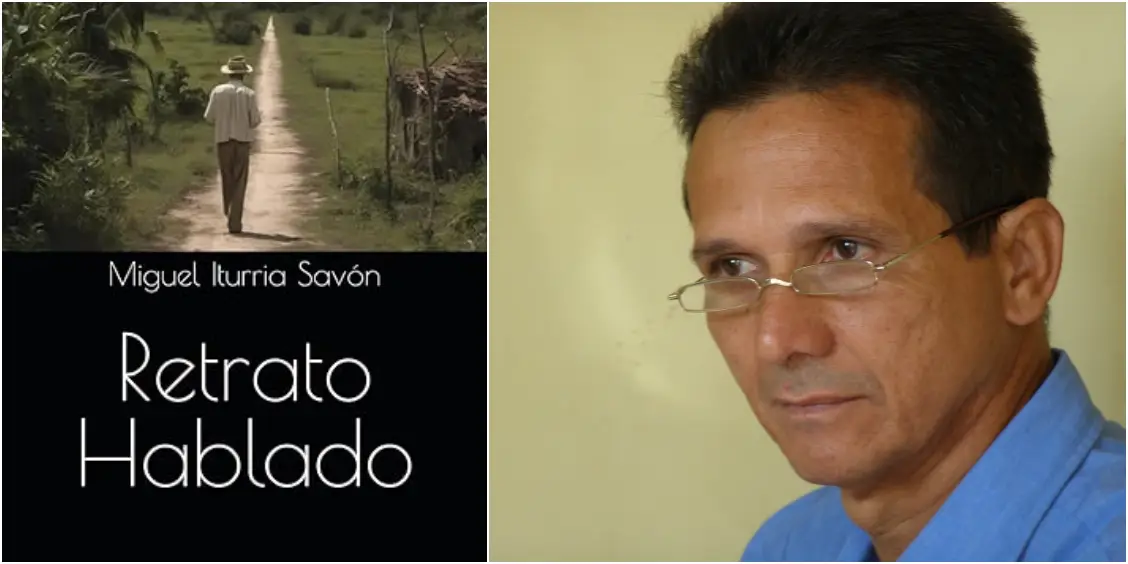

HAVANA, Cuba. – In spoken portraitthe first novel written by Iturria, who until now had dedicated himself to essays and historical and cultural research, tells in a stark way the eventful life of his brother Pedro, spent between marginality, crime and dementia.

“I am a little devil who survives without screwing up the lives of others with the story of the country and the future,” explains the protagonist in one of the first paragraphs.

It must have been very painful for the writer to relate – always in the first person – the sad and hard story of Pedro: born in the East of Cuba in the 1950s, orphaned from a very young age, moving from one relative’s house to another and then ―supposedly to readjust his behavior― through scholarships and psychiatric hospitals where an environment similar to what he would find in the prisons where he would finally end up prevailed.

The references to the context of the 60s, the time in which his adolescence developed, are very timely, mainly the description of what life was like at the scholarship school, the mansion in Miramar that was owned by an expropriated or shot millionaire:

“No one responded there, they were robots in uniforms… They changed our name to a number; They called us ‘the mayitos’, for the May Day school, as if we were sparrows… We called the maids ‘aunts’, ‘Makarenko’ to the teachers, ‘instructor’ to the sergeant who gave orders… We had to ask permission until to piss or shit, and march like soldiers before breakfast, classes and meals, in addition to listening to the Television Newswalking in single file and shouting: 1, 2, 3, left, right, stand firm!… We felt counted, stalked, watched; We were the Reserve of the Homeland, we had a mission and a glorious destiny. We were above all a number, we had to respond ‘present!’ and raise your arm like the soldiers in Russian and German films. If someone made a joke, did not salute the flag or forgot the assigned number, they were forced to march and endure a speech about the Revolution, the Homeland, the future… “

It would not take long for Pedro to express his rebellion against the barracks atmosphere of the scholarship. But when he escaped, the Carmelite uniform and military boots gave him away, “like the clothes of prisoners or the brand of cattle: they see you, they notify the owner and he collects and punishes the beast.”

After the scholarship, for committing a crime, he spent two years in the Bayamo prison and one in the Boniato prison, where he learned to paint, but, as he explains, “I got involved because of the youth hunters”: one of them got cut the face with a sharp spatula and threw the tray of food at another, which cost him five years for aggression and collective brawl.

“For me, prison was like the scholarship but without streets or sun; vomiting food (…). You have to fight for food – macaroni or cornmeal with bugs, a piece of sweet potato and soup without meat or noodles –, for bed, for cigarettes and for life.”

Starting in 1980, in Havana, Pedro would pass through the prisons of La Cabaña, the Combinado del Este, Taco Taco and the Mazorra Psychiatric Hospital. The writer thus summarizes what he describes as “a journey through hell”: “I lived 12 years behind bars, three on the streets and almost 20 in this circle of hell, surrounded by whores with nursing degrees, doctors who prescribe without looking at the who will swallow his pills, a manic psychiatrist, the barber without a razor who cuts our hair and our ideas, cooks who steal and sell food, drug dealers, stupid and crazy assistants who give their asses for coffee or tobacco.

The author wrote this dark novel-testimony based on what he heard his brother tell during his visits to prisons and asylums.

Miguel Iturria, born in 1953, resides in Valencia, Spainsince 2011, when he went into exile due to harassment by the political police for his work as an independent journalist. He has published the books Spaniards in Cuban culture, The Basques in Cuba and Cuban perspectives on García Lorca and Blue island on a red background: Cuban writers of the 20th century.