“We will never stop being indigenous.” It is with this phrase that Cacique Ademir Rikbakta of Beira Rio village, from Indigenous Land (IT) Erikpatsa, talks about the importance of preserving the culture of the Rikbaktsa people.

“We talk a lot to the community. I learned like this with my father. We talk a lot in the language. We have traditional dance and chicha is our drink. We will never stop making culture. Today, I’m with my people fighting.”

Beira Rio village was one of three visited by the team of Brazil agency on April 8 and 9. The struggle of which Cacique Ademir Rikbakta speaks is clear when the region is overwhelmed. The excerpts of the Amazon rainforest dispute space with soy and corn cultivation and cattle rainfalls. The indigenous land, surrounded by crop, feels the impacts of having less and less hunting and fewer fish on rivers, as well as counting fewer pollinators to keep the plants in the region.

The Rikbaktsa, according to the Socio -Environmental Institute (Isa), live in the Juruena River basin, northwest of Mato Grosso, in Ti Erikpatsa, Japuíra and hidden. There are 34 villages distributed throughout the territories, and the people have a history of struggle in defense of their lands: until 1962, the Rikbaktsa resisted against the rubber tappers advancing in the region to extract rubber.

In the 1960s, the Jesuits, financed by the rubber tappers, were responsible for the so -called “pacification” of the people. The process led to the difficulty of teaching the mother tongue, since Children, in boarding schools, were punished when they speak their own language and forced to communicate in Portuguese. With this, the Rikbaktsa language became the second most spoken, especially among the younger population. This pacification also led to the illness and death of 75% of the population and the loss of territory.

Today, the population has grown again, but the land disputes in the region remain, according to Isa, especially against loggers and prospectors.

“What we have here inside our community is culture. Our culture is the people,” says Cacique Ademir Rikbakta. “This is what we want to go to these new generations, these teachings. From the elders to this day, we have been learning too.”

Cacique’s wife, Angelica Zokdo, also fights for the resistance of culture. “I, as a mother, always say: you have to learn to do. We, as a mother, are teaching these children who are coming now too, then they show them [a cultura]as we are showing. The day we are no longer, it will be for them, ”he says.

The Rikbaktsa are divided into clans, being the main Makwaraktsa, which means yellow macaw, and Hazobiktsa, or red-headed macaw. Each clan and sub -group of ethnicity has their specific body painting, and that’s how they received the reporting team from Brazil agency. With paintings, crafts, dance and music.

Breaks Advance

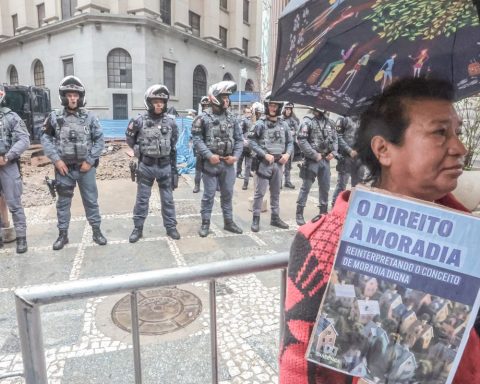

Although the search is to maintain customs, Indians no longer find in the territory everything they need to survive. In Pé de Mutum village, at Ti Japuíra, chief Francisco Rikbaktsa drew attention to the advance of the crops.

“We were big and we had plenty of fish and animal meat. You are seeing things are diminishing for us. Our custom is to eat these traditional foods. Today we are surrounded. Around, it is crop, and has the question of water contamination by pesticides. You are seeing, you are stepping here inside our village, inside the indigenous area. I say this to you, because we also suffer like one of you, ”he said to visitors.

In the Red Barranco village, at Ti Erikpatsa, Lauro Ruwai Rikbakta was one of those responsible for the meal served to the report, with hunting and fish. He said it is becoming increasingly difficult to find the animals.

“We did the impossible. This is tapir, and this one is fish,” he said, pointing to each of the food served. “Nearby, they started planting corn and soy. So the animal goes to the easiest place to seek food for it, instead of being here inside the bush.”

The hunt, which was found with a one kilometer (km) walk, is now about 15 km. To find some specific animals, you need to walk even more, about 60 km. The foods harvested are also more scarce. “Our fields [plantação] It’s the city, I’ll tell you the truth. ”

Culture in Education

In villages, the challenge is to make younger people interested in traditions and know the culture of which they are part. One of the strategies is to incorporate teaching in schools in the territory. At least once a week, students take classes on cultural practices, learn the Rikbaktsa language, dances and customs.

Professor Givanildo Bismy of MyHyinymyMykyta State School in Red Barranco is finishing the master’s degree, in which he studies indigenous literature. He seeks to bring to the classrooms these teachings.

“It is transforming so that children can have knowledge of the stories. This is a very important thing for us. We are already beginning to flow, it is already the protagonist of our own history, our own people. We, indigenous people, the people themselves, we are writing our story, that there is no one who wrote like this. And we started now,” says the teacher.

One of the difficulties in teaching culture is precisely the lack of specific materials. “We have very little of this material that is from our Rikbaktsa people. We receive the materials from the outside, which sometimes do not serve our people. It is not according to what we want,” says Professor Gesilene Aikdopa, from the same school.

At the State School Pé de Mutum, Professor André Apyton, responsible for teaching language, says the lack of materials impacts on teaching. Even because, there, students can’t practice at home, as many families have Portuguese as the first language.

“The idea is that they learn from families the speech in the mother tongue and, at school, they would learn more writing. But that is not happening. Families do not speak. Only the elderly who have dominance of the language. Then, at home, usually parents no longer speak,” he says.

Return to the community

For Gesilene Aikdopa, the intention of teaching culture is not necessarily to keep young people in the villages, but they know, defend the people and can, if they follow their studies, return and bring knowledge to the community.

“Just as they grew up, they were born here, we try to form them in each profession so that they defend us as well. Because they have many coming to the village to take our things. So, we also form to bring return to the community.”

Fulfilling this expectation is the dream of Rogerderson Natsitsabui, from the Pé de Mutum village. Today, at age 30, he continues in the village participating in projects and improving, with the dream of studying law to advocate for the people themselves.

“I believe that, in the future, I will, God willing, enter a college. For me, this is a breakthrough, but I will never leave what I learned here,” he says. “My focus, since when I started to participate in mobilizations, it was always right. I never gave up on that.”

As Cacique Ademir Rikbakta says, to Rogerderson Natsitsabui, some things may change, but he will never stop being indigenous.

“In the world, there are people who have a vision of the indigenous peoples where, if I have a iphone My, I lost my culture, I no longer speak my mother tongue. We need to show [que não é assim]to take [nossa cultura] From now on, show who we are. This I believe it strengthens us. ”

*Agência Brasil team traveled at the invitation of Petrobras, sponsor of the Biodiverse Project