The student’s eyes smile as the sound of the piano dominates the room and her senses. The teacher plays, teaches, but, in this place, she also learns. The notes of the song Noturno come from the fingers of pianist Renata Sica and spread throughout the living room of a house in the city of Araras (SP). Maria José Febraro, 75 years old, floats through time when she learns that the work was composed by a black woman like her, with hard-earned dreams similar to hers, with achievements from time to time and failures every day.

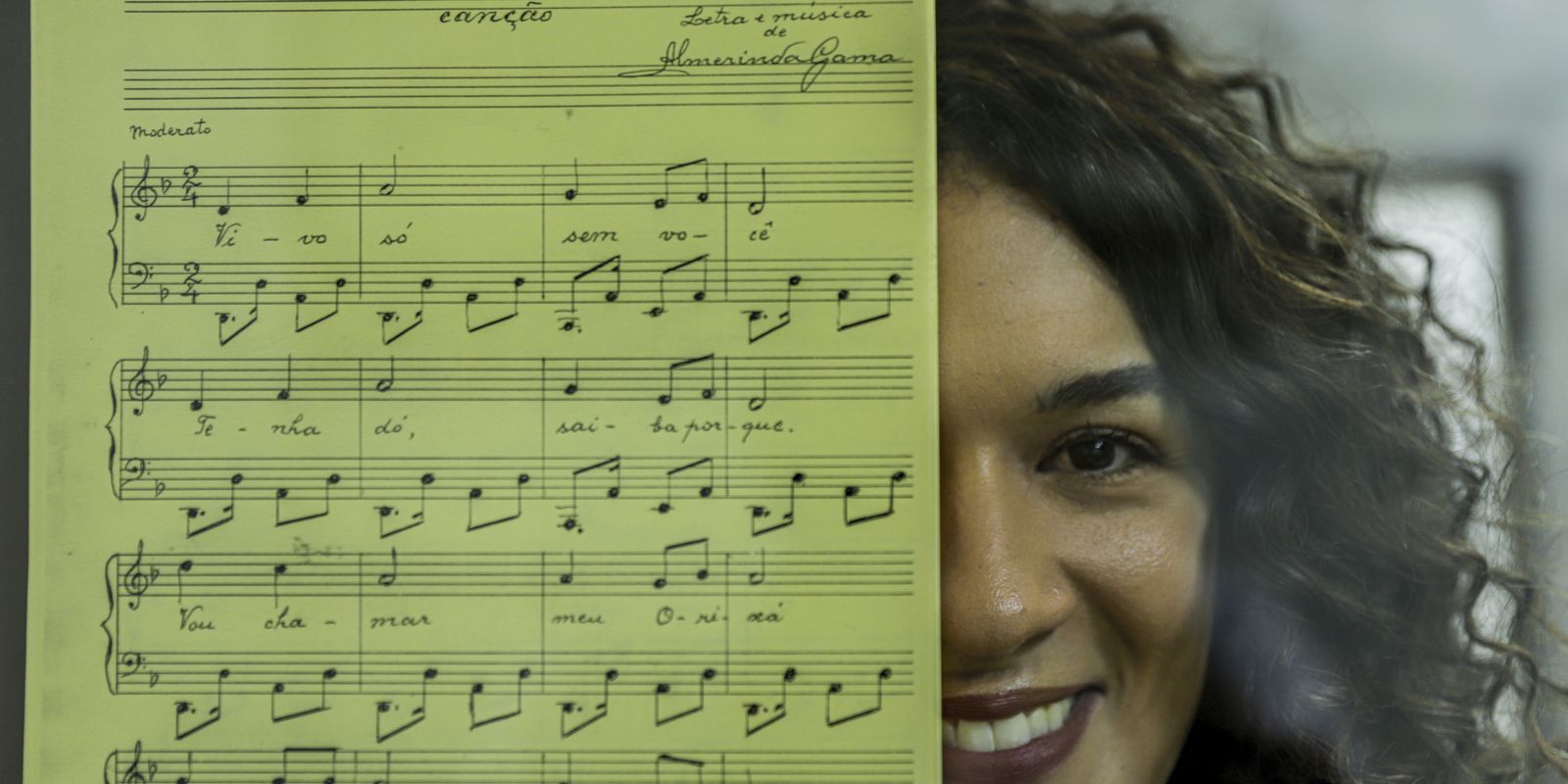

The author of the song was the suffragette, typist and trade unionist Almerinda Farias Gama (1899-1999). Almerinda was a historical worker from Alagoas, invisible in the 20th century and a figure previously unknown to the teacher who played, to the student who listened and to the world. They both know that they are facing a historical score with the yellowed marks of time.

The first to realize that she had a relic in front of her was researcher Cibele Tenório, a doctoral candidate in history at the University of Brasília (UnB) and journalist at National Radiofrom the Brazilian Communication Company (EBC). It was Cibele who found the scores archived at the National School of Music, at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Rhythms

Cibele will release, next year, a biography about Almerinda Farias (by the publisher Todavia). This biography was born from a master’s degree research at UnB, under the guidance of professor Teresa Marques. On the way to get to know more about Almerinda, Cibele discovered that the suffragist had a passion for the piano and had created music of different inspirations.

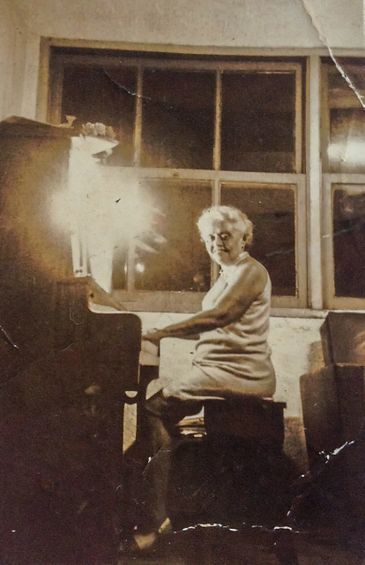

“We are talking about a character that has been forgotten”, says the researcher. Cibele explains that Almerinda, in an interview in 1984, recalled that her paternal grandmother taught her French, domestic skills and basic piano lessons. “She said she never entered a conservatory as a child. (…) Later, when she was elderly and retired as a typist, she returned to playing the piano, the instrument of her childhood”, says Cibele.

“It will ruin your fingers”

Almerinda’s trajectory enchants and moves Maria José, who also learned about the piano as a child. “Knowing about this story of struggle, from a black woman like me, made me want to learn the piano more”, says Maria José. The woman who listens to the instrument today has already heard it from her mother’s bosses, a maid on a farm, who doesn’t should get close to the piano in the house. “They said that if I touched it, it could ruin my fingers,” he recalls.

Today, the fingers and heart of the former farmer and maid find notes – the white keys – and their flats and sharps – the black ones – thanks to her neighboring musician Renata Sica. “I was touched when the Brazilian Piano Institute announced the discovery of the scores. I wanted to play. And it was like traveling back in time”, says the teacher.

Getting to know Almerinda

The disclosure of the discovery of the unknown scores occurred following the discovery of Cibele Tenório. Cibele was moved when she saw the sheet music in her hands and later, when she heard that yellowed paper becoming music in Renata’s performance. “It’s as if I were meeting Almerinda.” More than documents, music, in practice, revives the character. It stopped being just a story in a book and became a sung life.

“Almerinda played the piano when she was a child. He also spent his whole life at the keys of a typewriter. It’s as if she changed the keys. As a child, he switched the piano keys to those for typing. In his old age, he returned to the black and white keys.” The researcher explains that Almerinda said, at 85 years of age, that she had, throughout her life, written more than 90 songs.

The songs went to the National School of Music, in Rio de Janeiro. Cibele located 29 works and obtained access and permission for the material to be published. “Most have verses and have her handwriting. They are of different genres, such as baião, waltz, samba…. As she stated that there were more than 90 works, there is still a lot to sift through.”

The scores do not have identified dates and are about love, Amazonian legends (Almerinda lived in Belém) and even lullabies. “I started by first meeting the public figure, an activist for women’s rights. Then I discovered the sheet music.” The papers were an achievement, but the sounds took the discovery to another dimension.

Disclosure

The sounds also became possible because the researcher took the scores to the Brazilian Piano Institute so that the materials could be disseminated. “We have already published more than 4 thousand videos of scores by Brazilian composers [anônimos]”. After being published on the institute’s website, pianists became interested in making music not just on old paper. “Almerinda’s songs are simple. They can be played at home or in recitals”, says the president of the institute, Henrique Dias. He explains that the songs work on solo piano, but they can and should also be sung.

“What caught my attention the most was seeing the eclecticism of this intellectual. It shows what a vivacious and sharp mind she was”, says the pianist. For Cibele Tenório, the feeling of listening was different. More than method, roles and theory, there are feelings that the researcher cannot explain rationally.

“My encounter with Almerinda is also provided by ancestry. I am the daughter of a black woman and my research is, in some way, a reunion with my mother [que faleceu quando a pesquisadora era adolescente]”. The rescue is so that people are not forgotten.

Revolutionary

Researcher at the Advanced Program of Contemporary Culture, at the Department of Letters at UFRJ, professor Kátia Santos understands that stories like that of Almerinda, a black worker who was born 11 years after the abolition of slavery, are atypical and revolutionary situations. Kátia assesses that, even within black families themselves, art ends up not being the priority because survival has always been the most important thing. Almerinda’s conquest was not simple.

“Black women are the ones who suffer the most oppression […] They always have to come together to try to assert a space for themselves. But the basis of all this, so that these people have the opportunity to know if they have these skills, if they want to do this, is to guarantee education”, considers Kátia Santos.

For her, Almerinda’s story shows a civic need. “She wanted to practice art too. This is very important.” This need now belongs to Professor Renata, who decided to play and record the suffragist’s songs. A necessity also for piano student Maria José. “Since I was a child, I loved the piano. But I was very poor and had no chance of studying. Now, I can do it. Almerinda is another inspiration for me.” The silence was broken.