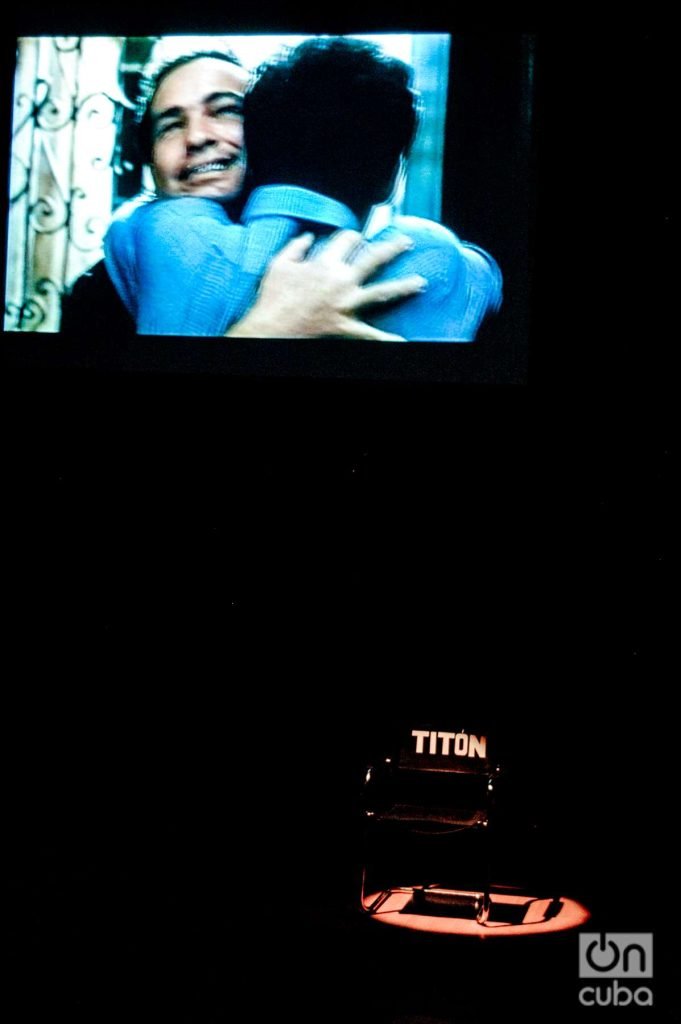

The movie Strawberry and Chocolate celebrates three decades of its premiere this year. At that time, in 1993, when I was barely 12 years old, I tried to buy a ticket for the old Baría cinema in my city, Holguín. I wanted to crash one of the evening shows, posing as someone who was 16, the minimum age allowed. How delusional! As expected, I was stopped at the box office.

It would not be until years later that he would finally be able to see the famous film by Tomás Gutiérrez Alea and Juan Carlos Tabío, starring Jorge Perugorría as Diego, and Vladimir Cruz in the skin of David; and with the unforgettable soundtrack of Jose Maria Vitier.

I don’t remember where, how or when that first time was; but the feature film was for me, as for so many Cubans, a one-way trip.

The plot, which takes place in the context of the Special Period, after the fall of the Soviet bloc, flies over time and retains an overwhelming relevance. That is where Diego and David, two names for the diverse in any of its expressions, retrace their steps, together facing a world of inequalities, prejudices (starting with their own) and intolerance.

The reality for sexual minorities in Cuba has changed a lot, especially since the approval of the new family law. However, in other aspects the country that the film represents, thirty years later, continues to yearn for an open debate on urgent issues: politics, economy, individual liberties. A collective conversation that, like the intimate one between Diego and David, becomes a deep reflection on acceptance, coexistence and meeting.

Every once in a while I go back to the classic film. Many Cubans have our own history of Strawberry and Chocolate or we rewrite in our own way “The wolf, the forest and the new man”, the angular tale of senel peace that inspired the movie.

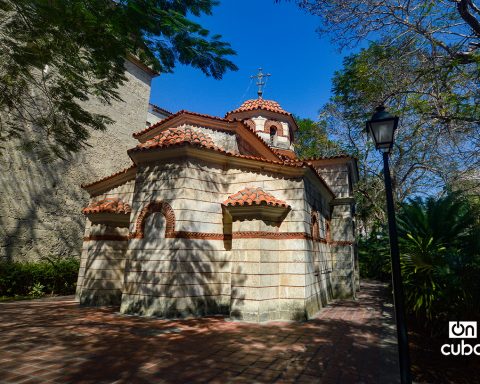

Several times I visited the main location of the film, at Concordia 418, Centro Habana. That’s where La Guarida was set up, an apartment baptized by Diego, “a place where not everyone is welcomed”, as David told him with a mischievous smile when he opened its doors for the first time.

the laira couple of years after the premiere of the film and international success with several awards and an Oscar nomination for best foreign film, it would become one of the most famous private restaurants in Cuba.

The first time I went it was closed; but the owners cordially allowed me to pass. There, in the midst of the silence and the light that entered through the windows, it was inevitable for me to evoke Diego and David in that small room with a high ceiling, surrounded by the sensuality of the paintings by Servando Cabrera, in contrast to the modest portraits of Martí and lezama. The two of them, face to face, in a game of arguments, whiskey in hand (“the drink of the enemy”), while Lecuona’s piano plays, or Cervantes with “Adiós a Cuba”.

I saw them laugh out loud at Diego’s bitter joke: “I have a friend who, since he was a child, had an extraordinary talent for the piano. But his father opposed it because of the fact that art is a thing for effeminates. Today my friend is 60 years old, he is a fag and he doesn’t know how to play the piano!”.

A few meters away, when I peek out of the narrow balcony where Diego shows David the same city he had visited so many times, I look at immediate Havana, decades later, and the landscape gives me back a portrait that seems intact. As if no time had passed; as if Diego could then also call fictitious relatives and, in the face of the inevitable silence, justify the absence for David: “They must be standing in line.”

There is no way to go to Coppelia, taste an ice cream and not look for friends at a table, with their complicit smiles. What a pity that the most iconic ice cream parlor in Cuba does not have a mural with frames of Strawberry and Chocolate. I fantasize that, on the giant screen at 23rd and L, scenes from the film shot on that corner will be shown; the same ones that Cuban Television would take twenty years to broadcast.

I would like to see them there again, returned to the environment immortalized by the film: Diego staring into David’s eyes, while he plays a role-play: “Wow… Today is my lucky day: I find wonders!” .

“How beautiful you are, David”, Diego answers, moved. “The only flaw you have is that you’re not a fagot,” returning to his sarcastic tone. “No one is perfect,” concludes David, dieguized.

A few years ago, in Gibara, Holguín, I came across the actors Jorge Perugorría and Vladimir Cruz in the middle of a crowd, singing and dancing at a concert of cimafunk. I didn’t see two actors, but their iconic characters. Outside the screens, the film continues and is spliced with real life.

immerse myself in Strawberry and Chocolate it always does me good. I don’t go to the film out of nostalgia, but to rediscover the roots of the present; for returning to the final embrace between Diego and David, a perfect metaphor for the Cuba I dream of.