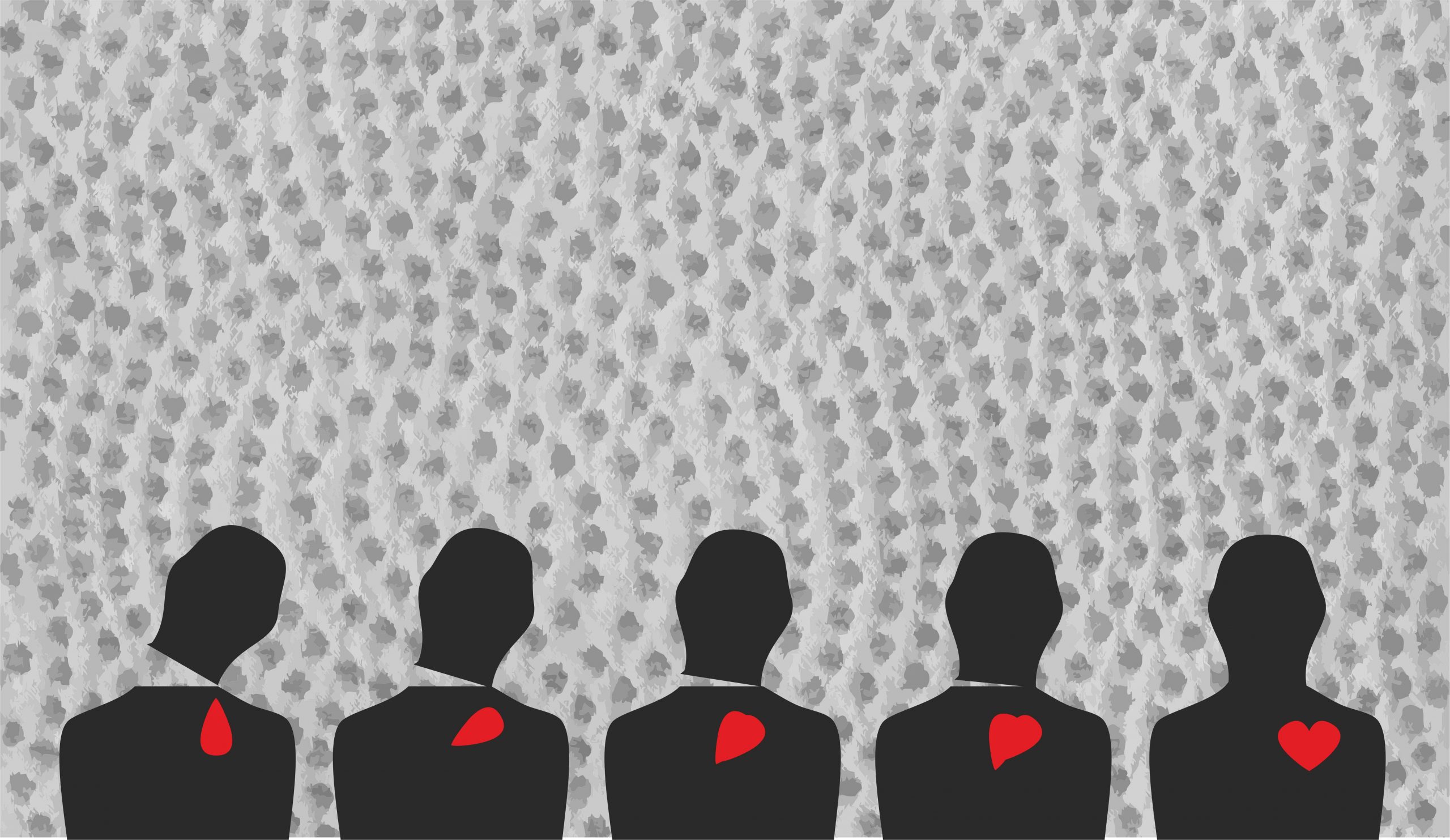

Racism is not a ghost that travels the world, but an invisible factory of stereotypes, exclusions and deep wounds on a good portion of Humanity. It is not simple aversion, but a social machinery that thinks, submits and punishes in subtle or violent ways, depending on the case. It cuts across philosophies and cultures throughout the universe. And in Cuba it was hidden, as years ago it was done with disabled children, political deserters and unfaithful women; none of them appeared in the family photo. Racism is a very familiar conflict in our society.

In the last thirty years, anti-racist criticism produced in Cuba has been accused of reproducing visions of other countries and cultures —read the United States or Brazil— and the most critical anti-racist activists are treated as radicals, dissidents or ungrateful; a triad that reduces the conflict to an overly simple analysis, more interested in diverting attention from the presence of racism that emerged in the only socialist country in the Caribbean. I call that neo-racism, a series of exclusionary and humiliating actions normalized in our daily lives and assumed, even, by many black people.

It is curious how difficult it is to identify racism in Cuba; Contrary to the sagacity with which we see any racist event in the world. Thus, we hide our aversion to talking about the subject here and we compare ourselves to those places where black people are regularly imprisoned and killed like Brazil or the United States. There is also racism in Spain, the Dominican Republic or Germany, but each racism is different, although equally painful. That is why in many countries laws and policies are denounced, discussed and designed, difficult to apply, but valuable achievements and tools of struggle. They are the recognition of a conflict, the level of discussion and consensus on it, plus the socialization of explanations and solutions that are lacking among us.

In Cuba, the debate on racism continues to be hijacked between salons, declarations and commissions that avoid any socialization of the subject. He is not the only black hole that, intermittently, superficially and opportunistically, is usually talked about a couple of times a year in some media space. The lack of a racial policy expresses slowness, incoherence and insensitivity to a problem that has not achieved legal consistency in any court, nor is it recognized as a cultural or institutional practice. Talking about racism has been banned for so long that it is still considered a very sensitive issue.

He was highly criticized Racist Halloween performance in Holguin, without offering context or its local history, marked by a high demography of Hispanic origin. Many analyzes are born from ignorance or lack of updating on the racial problem inside and outside the island. The young people in disguise, asking “Where are the blacks?” They returned home lamenting that the party organizers did not know that the KKK is a living force in the United States linked to the racism and xenophobia encouraged by Donald Trump.

Causing racial injury is a politically irresponsible act; Although these young people are not entirely to blame, they are the result of ignorance, that is, of their education. Are strange fruits of the Cuban neoliberal harvest, a boomerang of the ambitions of a middle class with economic power, culturally deceitful and inclined to american dream in its vernacular variant. Beyond the costumes or inserting Halloween among Cuban festivities, there is an economic, political and cultural model that, since the end of the last century, accommodates its exclusive values and reproduces them in the face of the shortcomings of the old verticalized model of the nation, little given to critically socialize the values of inside and outside. Both models coincide in their dependence on the Yankee commercial network, despite the blockade and its expected revivals.

The current Cuban racism is also renewed under other actors and spaces that do not name it, but use and control it as they please. It is a covert racism, sophisticated when it comes to gentrifying our cities or making certain neighborhoods and communities more precarious. It imposes new norms, tariffs and imaginaries, to which high bureaucrats, new entrepreneurs and nightclub doormen quickly adapt, regardless of their public or private status and the color of their skin.

The growing implosion of racist events in the country incorporates all the signs of the current political crisis. And vice versa: each of the signs of the crisis —although some do not take up the racial question— make visible the many variables that affect this population and mark their absence in key debates and sectors. On the other hand, the already exhausted, fragmented and co-opted Cuban anti-racist activism has a hard time raising its voices beyond the issues of entrepreneurship and black aesthetics, its academic niches and new self-promotional projects and actions, with middle-class aspirations ( no credit).

They are legitimate aspirations, but they lack the critical edge with which anti-racism was born in the 1990s in the midst of debates open to the public; with denunciations, catharsis and the recognition of a publicly aired social malaise. In less than a decade it became an anti-racist movement, with various tendencies, which ended up creating a political space, if not its own, very unique. That activism was dismantled by a strategy of power that eroded the anti-racist discourse to the point of seeing it surrendered by the promises, fears and uncertainties of the moment. The silencing or abandonment of critical discourse opened the way to a racist language that, in turn, reactivates the classist language that emerged in many post-11J discourses, not only when talking about blacks, but also when referring to poor, marginalized and street protesters.

That activism died, whose greatest inability was not to turn anti-racism into a cultural practice, part of the civility that we need to explain other conflicts. It was difficult to assume a culture of public responsibility and vigilance, as feminisms have achieved in Cuba, in spite of everything. Today this possibility is more distant than 15 years ago when Cuban anti-racism emerged as a criticism of the coloniality of domestic politics, that coloniality that configures socialist domination that I explain in a 2015 text, where I warn that: “The coloniality of the power has three great accomplices in Cuba: neoconservatism, internal colonialism and neo-racism, about which there is not enough public questioning”.1

Understand that racism and anti-racism are simply permanent experiences in our private and public lives. Not isolated or exceptional events, as the culturalist view usually sees it; but everyday and profound, structural and transcendent. Only racial prejudice, political cowardice and ignorance continue to evade the mechanisms of that great social machinery that is racism, beyond those who reject or reproduce it.

If the critical forces of a society cannot express their discomfort and aspirations, participating and debating their proposals, other ways of defending and celebrating the nation will emerge, other spaces of social and political resistance. There, a new anti-racism is emerging that blindly denies the previous one, although it feeds on its small achievements and lessons learned. The forecasts are not reassuring. Some rumberos from the neighborhood answered my question “Where are the blacks?” with ingenious replies: “We are not invisible. You know where we are. I do not have a passport. Etc.” They don’t know about strange fruits or cheap lemons. They live a reality without masks. Lacking. Hot…

In Key West, Havana, November 1 and 2022.

Roberto Zurbano. Cultural critic and anti-racist activist.

***

1 Zurbano, Roberto: Racism vs. Socialism in Cuba: a conflict out of place (notes on/against internal colonialism) in Revista Meridional (Chile), April 2015. There is a Cuban edition in Cuban Journal of Social Sciences, number 54, Institute of Philosophy of Cuba, 2021, p. 243.