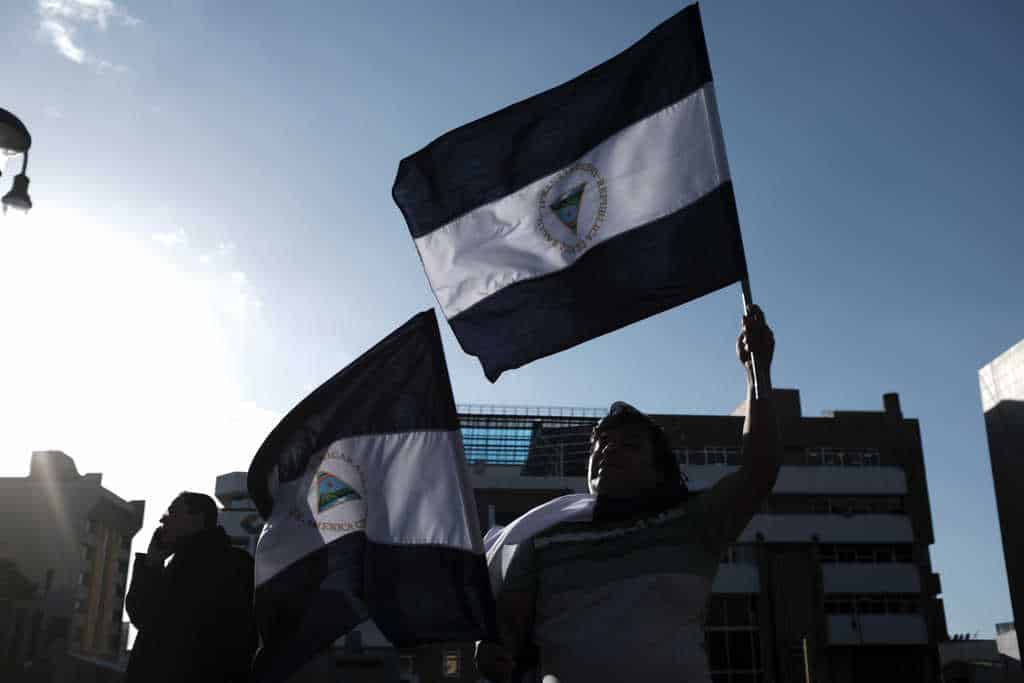

The stripping of nationality by the regime of Daniel Ortega and Rosario Murillo fell like lightning on the 317 Nicaraguans affected– 222 released on February 9 and another 94 on a list released by the Public Ministry of the dictatorship on the 15th of this month.

Some continue to assimilate it, while others take the first steps to discover how to get out of the migratory limbo in which they find themselves due to the repression of the regime. Their main demand is that asylum or refuge processes in third countries be expedited and that the governments that established their nationalities create mechanisms to put their political statements into practice.

Amaru Ruiz is a refugee in Costa Rica. He went into exile at the end of 2018 due to prison threats by the Ortega regime, which also confiscated his de facto assets, before he along with 93 other Nicaraguans were expropriated by an illegal judicial resolution and described as “traitors to the homeland.” The environmentalist has already requested his documentation in Costa Rica to ensure that he continues to carry out his work as a defender, while he studies the various scenarios in the face of his sudden loss of nationality.

Ruiz points out that both the countries and those affected were not prepared to act in the face of an event that transcends the history of the dictatorships themselves in Latin America, whose authoritarian governments have rendered political opponents stateless, such as the Augusto Pinochet dictatorship in Chile. However, never in a group as large as the case of Nicaragua: 317 people in less than fifteen days-including the bishop and political prisoner, Rolando Álvarez-.

Spain, Chile, Colombia, Argentina and Mexico offered their nationality to “stateless” Nicaraguans. Ruiz appreciates these public and political declarations from the governments, but also demands that operational mechanisms be established to manage these citizenships, whose requirements must consider the vulnerability of those affected by the elimination of their records in Nicaragua.

“It is a procedure, it is not by decree that they are going to give it to you -citizenship-. You have to make an application, a whole presentation, you don’t know about the times because each country is different, not all of them, perhaps, will have the same procedure, ”she said.

In his case, he remains expectant before the pronouncement of the Costa Rican authorities on the “stateless”. Until now, the Government of President Rodrigo Chaves, pointed out on February 21 that Nicaragua violates international law and conventions on statelessness, with the “arbitrary deprivation” of nationality. But he has not offered his Costa Rican nationality and has not indicated what consequences would have if a Nicaraguan refugee opts for another nationality, but wishes to continue residing in that country.

Living without a nationality

Economist Ligia Gómez, former manager of Economic Research at the Central Bank of Nicaragua and former political secretary of the Sandinista Front, has been seeking political asylum in the United States for more than four years. Her immigration status changed on February 15, when the regime stripped her of her nationality with a swipe of its claws. Gómez, who denounced the abuses of the Ortega regime before a commission of the US Congress, assures that she will remain “stateless” until her asylum process advances. The lawyers explained that if she accepts a nationality proposed by another country, she loses the possibility of obtaining international protection in the United States.

“The only solution that the lawyers give us is to remain stateless, waiting in indefinite immigration limbo until the US conducts a credible fear interview,” he told CONFIDENTIAL. Gómez, when reflecting on the possibility of another nationality, thinks about job uncertainty, since in the United States he has a work permit, and although he does not practice his profession, he works with civil society organizations, which allows him to support his family.

“In practice, according to what the lawyers say, I will be left without the human right to have a nationality for a long time. I cannot move, I cannot travel, I cannot -do- anything. I am practically locked in this migratory limbo,” said Gómez.

On the other hand, Mildred Rayo is one of the 222 people released from prison and exiled from her country on February 9, 2023. The only thing she knew when she arrived in the United States was that she entered with a humanitarian parole and that they could manage their work permit.

After fifteen days in the US, Rayo, who is a member of the Nicaraguan University Alliance (AUN), has a slightly clearer outlook. He decided to stay in the US and start his asylum process. He applied for a work permit and hopes to continue making progress in his regularization. One of the factors that influenced his decision was the territorial proximity of the US to his land.

The United States, which welcomed the 222 Nicaraguan exiles, assured that they would assist them in their efforts to regularize their immigration status. However, other exiles, like Gómez, explain that the asylum application processes are slow and can take years.

Retaliation for international defense of DDs. H H.

Uriel Pineda is a human rights specialist and lived in Mexico when the protests broke out in Nicaragua in 2018. However, the Ortega regime included him on the list of 94 people declared “fugitives from justice” in retaliation for his international complaint about the regime abuses against citizens.

Pineda considers that given the loss of his nationality, his situation is “greater vulnerability” because he was in Mexico for professional reasons, and did not have international protection as a refugee, which is the situation of the majority of “stateless persons.”

“To date, I do not know the status of my residence in Mexico,” says Pineda. One of his first actions was to request the Mexican Foreign Ministry to ignore the decision to violate human rights by the Ortega regime, to strip him of his nationality. However, the institution has not ruled on the matter.

Pineda also asked the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) for precautionary measures with an extraterritorial effect. This implies, if they are approved, that the IACHR, in addition to requesting information from the state of Nicaragua on their cases, requests that other countries signatories to the Commission provide the group of “stateless persons” with the protection indicated by International Law. This translates into generating facilities for political asylum, refuge or statelessness.

According to Pineda, the main effect of these extraterritorial measures is that all the “stateless” can continue to carry out the work of defending human rights and not immobilize them, as Ortega wanted. For his part, he still values the best ways to regularize his residence in Mexico.