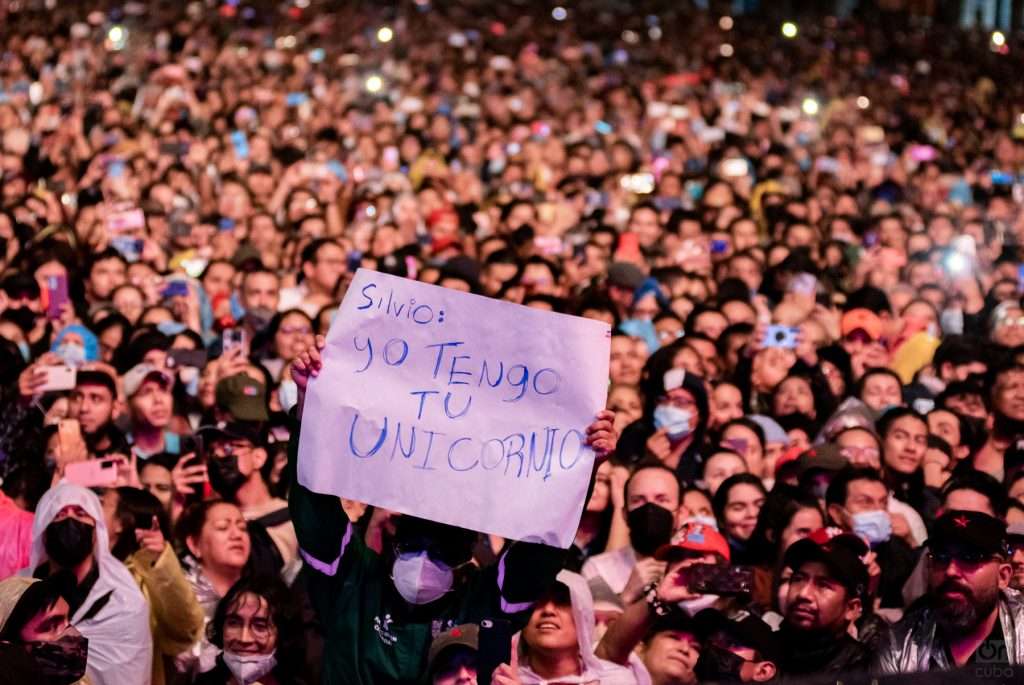

Almost a month has passed since the concert of Silvio Rodriguez and his music partners in the Zócalo, in Mexico City, and the melting pot of faces and feelings of the more than one hundred thousand souls gathered that night, are not erased from my retina. Voices still resound in my ears under the drizzle cheering Oe, oe, oeeeee, Silviooo, Silviooo! or singing in unison “Oleo de mujer con sombrero”, “Ojalá” and “El necio”, among other emblematic songs. I remember the photos of that evening. I reread some notes that I took in various parts of the night (because my camera wasn’t enough to record so many sensations), and I shudder.

That recital was a long-awaited reunion. Historical. The singer-songwriter and the Mexican public vibrated once again after a long impasse of eight years, since his last tour of Mexican stages. In addition to ending that long wait, it was epic to get back together, hug and sing like this, in a great concert, after the tortuous pandemic and the long confinement to safeguard life.

For all this and more, from very early on that Friday morning, there was already a long line waiting for the concert.

Also because of that love and fidelity at night, when it rained, minutes before the Cubans came on stage, the hundred thousand people did not leave the recital. The applause was heard with more effusiveness and, from the stage, it could be seen how a sea of umbrellas covered the historic plate of the largest and most important plaza in Mexico.

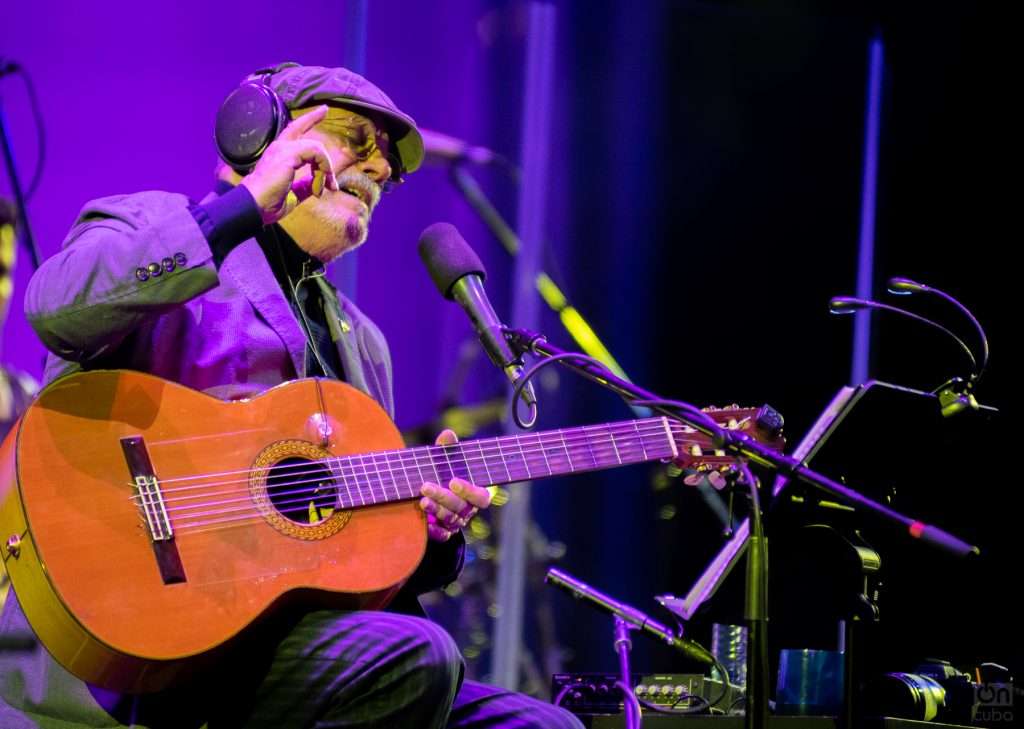

Given this context, Silvio, the musicians and the technical team reciprocated with a memorable evening of almost three hours, with a longer, more meaningful and powerful repertoire, even, than the one presented at the National Auditorium of Mexico, where they performed twice , in that same week.

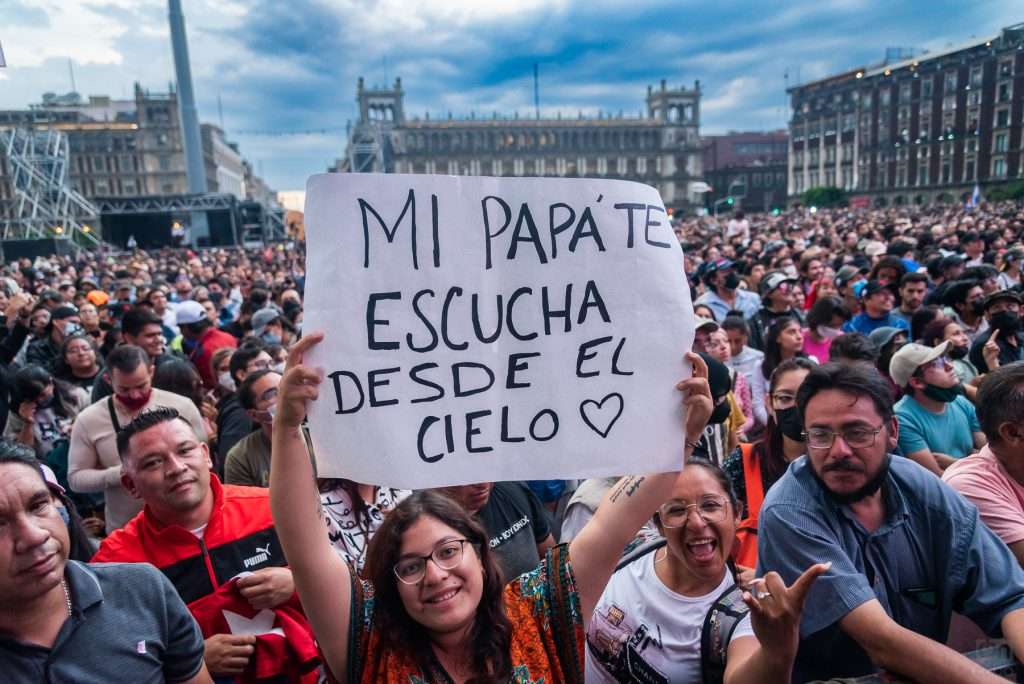

Seeing the Zócalo, approximately 46,800 m², overflowing with people and under a downpour was impressive. That figure of more than one hundred thousand people gathered to listen to Silvio surrounded by his songs, with great musicians accompanying him and a simple lighting design is much more than a quantitative figure. Diving into this tide we find a sociological phenomenon to highlight: an overwhelming generational diversity. In addition to those in their sixties and seventies, the age group that par excellence we could say are the majority of the followers of the author of “Ojalá”, there are more than twenty-somethings and thirty-somethings who mix with those in their forties and fifties.

Most of those who make up this youth group arrived at the recital with the expectation of seeing Silvio live and direct for the first time. And they were not hand in hand with his parents who, surely, bequeathed them the troubadour’s songs and records because they are an inescapable part of the soundtrack of their lives. Those young people were there with their friends, in a brotherhood atmosphere, exactly as their parents did in the 1990s and even the parents of their parents —those contemporaries with Silvio—, in the 1980s.

There were those girls and boys who were already before dawn in the vicinity of the Zócalo, in the line that was assembled as the day went by, waiting to get a place near the stage. And there, at night, you could see them in full concert, defying the rain, squeezed into the crowd, those fresh faces excited and drunk with joy chanting “A woman has been lost / to know the delirium and the dust, / this beautiful madness,/ her brief waist/ below me./ My way of loving has been lost,/ my mark on her sea has been lost”.

Why do these songs, some composed more than three decades ago, when these young people didn’t even think they were born, penetrate so deeply into that youthful mass? What do these songs have to do with your dynamics and contemporary realities? Some explanation, among many others, can be found in the vital function and ability of art to accompany us in the course of our personal and collective histories. It is a perennial exercise in critical awareness and, in turn, an embrace of hope.

It is like a philosophy of life. There is an extraordinary path carved out by the poet to describe and translate tangible, everyday, routine and sentimental issues that we mortals go through. Love, rage, pain and more is not a fashion. It is a constant part of life. In this case, a song by Silvio —nor any other by any author— transforms the world, but it does have the unique ability to accompany those who, like these young people and others, are convinced that life is beautiful and colorful, as Silvio himself on his album Rodriguezwhich his father instilled in him.

Another of the issues that I think brings Silvio closer to this multigenerational audience is his ability to escape complacency, easy things and accommodations. Even from the labels of success. It is not due to his audience but to himself and his work. I have the feeling that he seeks to be disruptive all the time. Moreover, I think he dodges his own legend. He crushes his own shadow. He always was and always has been.

At this point, the singer-songwriter could fill theaters and plazas with a clean guitar and a repertoire made up of his most emblematic songs. Play a couple of chords and let the audience sing to the end. However, he always reinvents himself. He takes risks and challenges. Silvio, surrounded by exceptional musicians where generations, musical formations and styles come together, is capable of proposing new songs and arrangements.

Precisely the band/family that accompanies him has been an inescapable pillar for a long time: Rachid López on guitar, Maikel Elizarde on tres, Niurka González on flute and clarinet, Oliver Valdés on drums and percussion, Jorge Reyes on double bass, Jorge Aragón on piano and Emilio Vega on vibraphone. In the sound controls are Olimpia Calderón, Enzo Estrada and Jerzy Belc (El Polaco). On stage, in the details of the organization, Amin Blanco and Mirta Almeida and the Argentinians Fernando and Martín, from Alfiz Producciones, among other “essential invisibles”.

With the line up musical out of series, which has accompanied him for a few years (some for decades), the troubadour molds his arrangements and melodies in a collective, exquisite and arduous work. From that creative laboratory have come the arrangements of songs as diverse as “Danzón para laespera” or “América”. And iconic pieces that are established in the public’s sentimental imagination, such as “Días y Flores” or “Oil painting of a woman with a hat”, arrive fresh and with a musical twist that seem to have just come out of the oven.

In this combination of factors appears the sustained creative capacity of the troubadour throughout so many years of career. The professional moment he is going through is excellent. “The story happens to Silvio but it seems that he doesn’t spend time”, I heard a girl say in the Zócalo. And it is true. Silvio keeps his pen sharp and tender. Among the many examples, I expose two of the songs from his album “Para laexpectation”, published in 2020, in the midst of a pandemic. One is “The thing is coming”, where he warns that the thing is coming, no matter how unfair and offending;/ the thing comes to exhibit total self-confidence;/ the thing comes invoking what suits it,/ because the noble moral. And the other is “After living” where he confirms “… what needs to be saved./ For example, what I know: / my good luck in finding / everything, even what wasn’t”.

It also holds your voice. It sounds clear, clean, careful and natural. Technicians do not need to resort to some camouflage of those that new technologies bring today to project something that is not outwardly. It is Silvio as always: in body, pen, voice and soul. And, like a high-performance athlete, he more than sings thirty songs in several concerts of more than two hours each. As if that weren’t enough, when he finishes, already downstage, when he has lowered the curtain, he doesn’t look tired. Rather, with energy for a few more encores.

About the massive call for their concerts is something that has happened since the eighties of the last century. It should be noted that in 1989 he undertook the “Tour for the homeland”. He began with a guitar concert at the Pico Real del Turquino, in the Sierra Maestra, at the highest point of the island, in the shadow of the José Martí monument. The singer-songwriter continued his journey from East to West, accompanied by the Afrocuba band. Two months later he ended up in Havana, in a packed Plaza de la Revolución. Throughout Cuba, it is estimated that tens of thousands of people attended these recitals.

They were followed by presentations at the Karl Marx Theater, the Coliseum of the Sports City of Havana, other national tours such as “Towards a Culture of Nature”, in 2005, through prisons and, in the last decade, through more than one hundred Cuban neighborhoods. in what Silvio himself has called “the endless tour”.

Beyond the seas resounds, for example, the Las Ventas bullring in Madrid, the largest bullfighting colossus in Spain, where the album “Mano a Mano” was recorded live at full capacity, which Silvio shared with his friend Luis Eduardo Aute, on September 24, 1993. And last year, almost coming out of the pandemic and also in the Spanish capital, it filled the WiZink Center micro-stadium. The same thing happened in 2010 on tour in the United States in cities like Washington, Orlando and even the legendary Carnegie Hall in Manhattan. In 2017, in New York’s Central Park, they also enjoyed a live Silvio concert.

In Latin America, the calling phenomenon occurs with greater force. Argentina, Chile, Uruguay, Ecuador, Bolivia, Mexico, Panama and the Dominican Republic have been some of the countries visited by Silvio. In Argentina, after appearing for the first time with Pablo Milanes in 1984, at the Obras Sanitarias stadium and offering 14 concerts in a row, he landed in 1985 at the imposing Luna Park stadium. From that year until 2018, which was his last performance on this stage, the “sold out” sign was a constant. In Santiago de Chile, in a legendary performance at the National Stadium, in 1990, before 80,000 people, he recorded the album “Silvio Rodríguez en Chile”, with Chucho Valdés and Irakere and Isabel Parra and her group as guests. On the tour of the southern cone in 2018, which included a tour of cities in Chile and Argentina, he closed his performances before a hundred thousand people in a free concert on an avenue in the city of Avellaneda.

In the Zócalo this was the fourth time that the founder of the Nueva Trova Movement appeared. The first was in 2005, then in 2007 and on March 29, 2014, for the third time, he also filled this site, like now, with more than one hundred thousand people.

I return to the photos of the concert in El Zócalo. I pan my gaze over the faces and their expressions, now frozen within the snapshots. They say a lot. It is something that goes beyond what is strictly cultural and artistic. It will take a long time for me to measure in its proper measure the feat carried out by the troubadour and the public in the Aztec capital, of meeting in the rain and in these times, to vibrate to the pulse of songs.