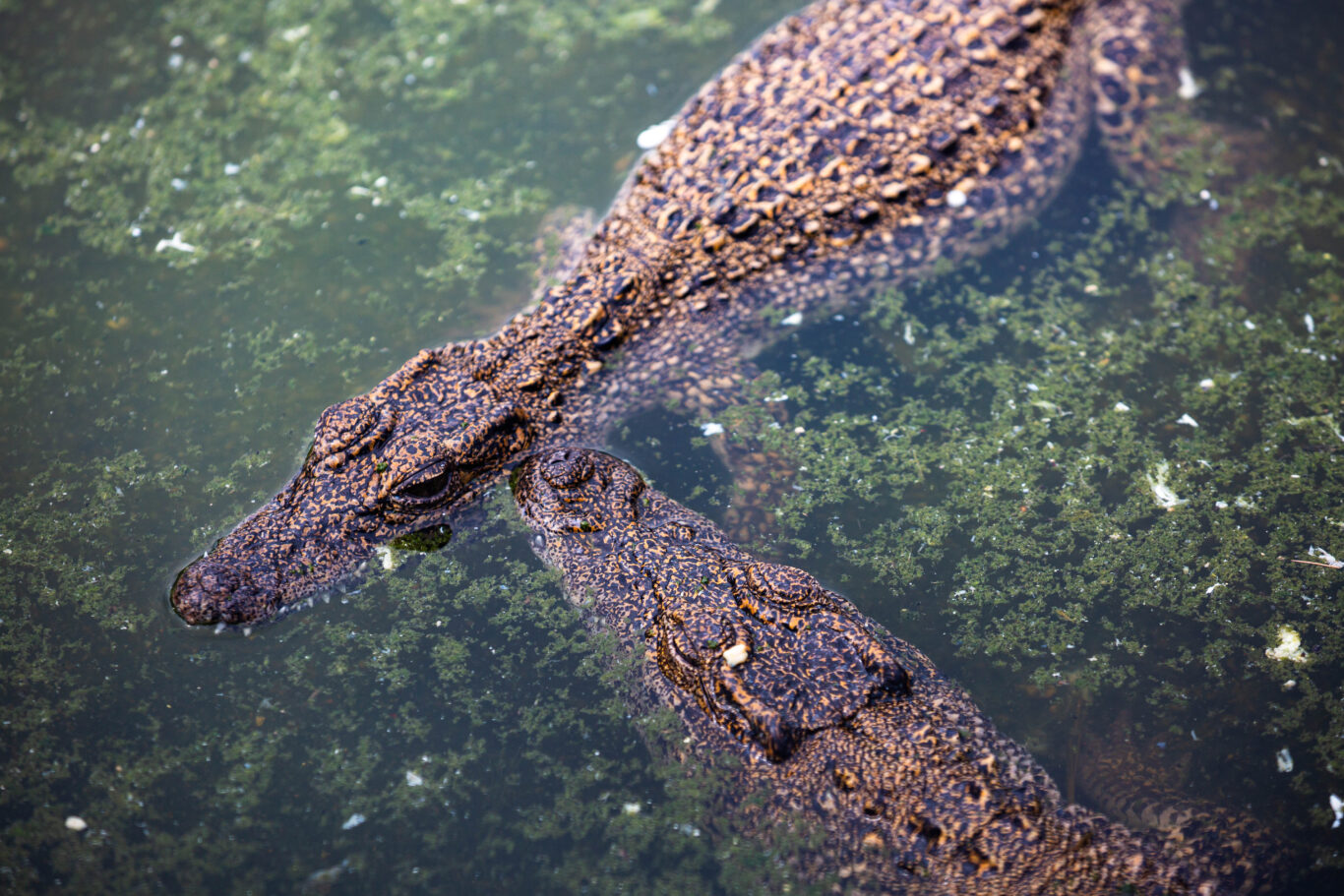

Until next February, the project “See you soon, crocodile.”promoted by the United Nations Development Program in Cuba (UNDP), will receive donations through the Every.org site with a clear and urgent objective for endemic environmental conservation: the monitoring of the Cuban crocodile, a species in danger of extinction due, among other factors, to illegal hunting.

He Crocodylus rhombifer (known as the Cuban crocodile) inhabits the region of the Ciénaga de Zapata, a swampy and peninsular ecosystem located in the province of Matanzas. The species, which can only be found in this wetland, has been classified as Critically Endangered by the Red List of Threatened Species of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

“This is due to the small number of estimated adult specimens in free life (about 2,400), their small geographic distribution range (300 km²), illegal hunting, hybridization with the American crocodile (Crocodylus acutus) and habitat modification,” he told OnCuba via WhatsApp the biologist Etiam Pérez, in charge of the project.

Once the fundraising campaign is concluded, which will allow the team to purchase appropriate equipment for the tasks of labeling and monitoring the specimens, they will be in charge of Pérez and Gustavo Sosa, veterinarian. Both lead field and conservation work.

To learn more about the project, which is part of an alliance between the Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation of Nature and Man (FANJ), the Company for the Conservation of the Zapata Swamp (ECOCIENZAP), the Group of Crocodile Specialists of Cuba (GECC), CITMA and the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) in Cuba, OnCuba spoke with Etiam Pérez, Graduate in Biology (2002) and Master in Zoology and Animal Ecology (2013), who since his graduation has worked in the Crocodile Farm of the Company for the Conservation of the Zapata Swamp, contributing his experience to the care and preservation of this unique species in Cuba.

What factors have historically put the Cuban crocodile in danger and what threats persist today?

There is evidence that suggests that hybridization is ancestral and is probably due to the evolutionary closeness between species, since there is little time for divergence.

Hunting, illegal or not, has had a considerable impact on populations of C. rhombifer. Fossil records found on some Caribbean islands and in the Bahamas show that the species had a broader distribution, which was drastically reduced with the arrival of Europeans.

During the first half of the 20th century, the skin trade led to the extraction of approximately 90 thousand crocodiles in the Zapata Swamp. Although species were not always distinguished, it is estimated that the majority were C. rhombiferdue to the better quality of their skin and their more aggressive behavior, which made them very vulnerable to hunters. After years of ban, the population is once again under pressure from illegal hunting, especially during the crisis of the 1990s, and currently this remains the greatest threat.

Habitat modification by human activities has also negatively affected the species. Since the arrival of Europeans to Cuba, changes have occurred in the ecosystems it inhabits, such as deforestation, construction of canals for the extraction of wood and charcoal, and the drying up of small bodies of fresh water for agriculture and human supply.

What does the joint work you do for the preservation of the Cuban crocodile consist of?

Look, more than a project to conserve the Cuban crocodile, what we have is a program for the conservation of the genus Crocodilus in the Zapata Swamp. As I mentioned before, hybridization occurs between the Cuban crocodile and the American crocodile, the two species of this genus that we have in the area.

Now, many consider hybridization as a threat, but for some specialists, like in my case, it does not necessarily have to be. What is happening is that we have a very local population; The Cuban crocodile is only here in the Ciénaga, and probably what we are seeing is a natural process where two species are coming together. The most likely thing is that speciation will eventually occur, that is, a new species will be born.

The American crocodile population here is not large enough to displace the Cuban one, and today what we see most are hybrid specimens. Therefore, the American crocodile population and the hybridization process are also important to us; They cannot be seen separately.

Now, speaking of the conservation of the Cuban crocodile within this program, we have two fundamental lines: conservation on site and ex situ. The on site refers to actions on natural populations of the Cuban crocodile, and the ex situ It is what we do in captivity, from our institution.

In captivity we are dedicated to maintaining a population that is used to study biology, behavior, physiology, in short, aspects that can be complicated to investigate in the wild. These results serve as a baseline to later explore in the wild, with more specific experiments and research designs.

In addition, we use some specimens for reintroduction. We release captive-bred crocodiles, especially small ones, in areas close to the hatchery. We also use them with national and foreign students, and as part of our research on the effectiveness of these releases in free life.

In wild populations, we focus on animal health studies under the concept of “One Health”. This means using a species to learn about diseases or its state of health and, from that, inferring the health of ecosystems. If ecosystems are healthy, human populations will also be healthier and more resilient to climate changes.

Additionally, we conduct studies of molecular genetics, movement ecology, geographic movement patterns, habitat selection, and factors that influence where crocodiles live. We also monitor the population: how many there are, how many hybrids, how many males and females, young and old. This takes many years, requires many samples and visits to the areas in different seasons of the year.

What institutions and specialists are currently participating in the project and how is the work coordinated between biologists, veterinarians, field technicians and other local actors?

The program is led by the Company for the Conservation of the Zapata Swamp, and very few institutions in Cuba participate: the University of Havana, the Faculty of Biology, some Flora and Fauna specialists, and us, the two main specialists: me, a biologist, and Gustavo, a veterinarian. In addition, we have crocodiles, who handle the crocodiles in captivity, feed them, clean the tanks and help us in the field.

We also occasionally collaborate with CITMA and the State Institute of Veterinary Medicine, and maintain relationships with foreign institutions for particular research. As for local actors, we work with communities in the area, mainly as guides, because they know the territory well and can react quickly to any problem. We have also collaborated in environmental education, with local communicators who help us spread conservation campaigns.

In the case of releases or reintroductions, what criteria do you use to select the most suitable sites for the survival of the specimens?

To release crocodiles into captivity, we consider several factors: the release area, the presence of American crocodiles, the availability of food, the proximity to human communities and the protection of the site against illegal hunting. For this reason, lately we have released small specimens: they are less attractive to hunters and have time to adapt to the environment.

How did the idea of launching the initiative come about? crowdfunding “See you soon, crocodile”? What motivated you to turn to a crowdfunding model for a conservation project?

The initiative emerged a couple of years ago. The Antonio Núñez Jiménez Foundation (FANJ) and the UNDP suggested that we try this platform to finance conservation projects. More than just getting money, we found it interesting as an experience in Cuba. We will collect funds until February; Then it will take several months to buy, build and test the transmitters, obtain permits, etc. We estimate that in about five or six months they will be operating, collecting information on georeferencing of the released crocodiles.

What type of equipment or specific actions can be financed with the resources raised?

In addition to the transmitters, we carry out environmental education actions with local communities and tourists, so that they understand the importance of the species and reduce the demand for crocodile meat or skin. The funds also help finance field expeditions and monitoring of the specimens.

What indicators are you using to evaluate whether preservation actions are working?

Measuring the impact of environmental education is complicated and takes many years. For example, assessing how many children actually change their behavior towards biodiversity is something that can only be seen over time. Estimating the Cuban crocodile population is also difficult due to hybridization: distinguishing a Cuban from a hybrid is easy at first, but after several generations they look very similar and only molecular analyzes allow us to correctly identify them.

We are currently in a process of monitoring and taking samples for large-scale molecular analyses, which will allow us to evaluate the status of the population and the effects of our actions in the next 3 or 4 years.

Regarding the initiative of crowdfundingits objective is not a direct impact on conservation, but rather to collect ecological information that allows us to make better decisions in the future, such as selecting optimal reintroduction sites.

What role do the local communities of the Ciénaga de Zapata play in this project? Is there an educational or participatory component associated with the campaign?

The role of local communities also includes environmental education. We seek to involve them, identify people motivated by conservation and promote rational use of natural resources.

What do you dream or envision for the future of the Cuban crocodile in the next 10 or 20 years?

We would like to see the Cuban crocodile population restored to the historical levels of 300 or 500 years ago and for their habitats to be healthy. The reality is uncertain; We are few people working full time and we face threats such as illegal hunting.

Without our program, in five years there might not be any specimens left in the wild. Therefore, although the future is uncertain, our work is essential to keep the species and its habitat alive.

If you want to help, learn more about this initiative or share the contacts of people, institutions or networks that may be potential donors, you can write to: [email protected].