The search in Brazil for minerals used in the energy transition accelerates the climate crisis in Pará (PA), Bahia (BA), Goiás (GO) and Minas Gerais (MG), the main ore producers in the country, with “considerable changes in short -term climate standards (by 2030)”.

This is the conclusion of unpublished study released on Wednesday (23) by the Mining Observatory from data prepared by the consultancy TMP, which analyzes extreme climate events.

“A lithium mining company arrived in the Jequitinhonha Valley [MG] and knocked over a thousand trees in a semiarid region like ours. The impact on air and water quality is very large. The Araçuaí River and the Jequitinhonha River are almost disappearing, ”warned the 58 -year -old indigenous Cleonice Pankararu.

The leadership of the Pankararu people live in a village in the municipality of Araçuaí (MG) near lithium extraction areas – one of the most sought after minerals in the energy transition industry, used to produce electric car batteries.

Heat and heavy rainfall, increased consecutive dry days, annual loss of rainfall and extreme temperatures are some of the climatic effects expected with the expansion of mining in these states.

“Mining has been sold as a sustainable green” solution “to energy transition. We are leaving a fossil dependence to another even larger mineral base that requires the opening of hundreds, perhaps thousands, from Minas Gerais in sensitive areas, such as the Amazon and the Cerrado,” explained the director of the Mining Observatory, Mauricio Angelo.

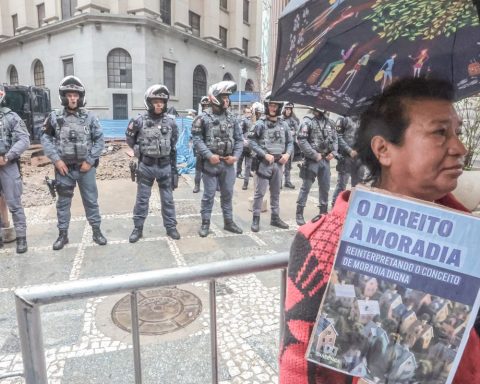

Observatory consultant Gabriela Sarmet stressed that the report shows that climate security is at risk for geopolitical dispute for these transitional ores. “We are creating sacrifice zones in Brazil to meet the demand for decarbonization of the North,” he said, referring to the most developed countries, located mainly in the northern hemisphere.

Of the mineral fossil base

Expert Mauricio Angelo, a doctoral student in Environmental Science from the University of São Paulo (USP), warned of Agência Brasil that a mine is always accompanied by gigantic infrastructure works with considerable environmental and social impacts.

“Anchored in the best scientific bases, our predictions show that the energy transitional gas emissions will be huge. You can’t say that the energy transition is ensured by changing a fossil base to a mineral base. We are exchanging one problem for another,” said Angelo.

For the expert, it is necessary to overcome the current development model to alleviate the climate crisis. “We have to question the pattern of consumption that we often import to Brazil from the United States. This standard of production and consumption is incompatible with the boundaries of the planet,” he said.

The study recalls that Brazil has been positioned as one of the main suppliers of minerals for the energy transition. Investments of US $ 64 billion by 2028 are foreseen for the expansion of the mineral sector in the country.

Lithium valley

The indigenous territory where the village of Cleonice Pankararu is in the Jequitinhonha Valley, has been called the lithium valley due to the large reserves of the mineral used in the energy transition.

Indigenous leadership told Brazil agency That mineral extraction in the region began in 2017 and that, since then, dynamite explosions, dust of mines and river contamination have caused health problems in the local population.

“Before the lithium, I didn’t have so much health problem. We fluctuated and it took to fluctuize again. Now, we constantly fluctuize and we have a lot of gastrointestinal problems. It’s really.

Minas Gerais holds 80% of national lithium reserves, and the main extraction hub is the Jequitinhonha Valley. “With seven other projects in progress, it is expected that lithium production will increase five times by 2028 and attract $ 6 billion in investments in the next decade,” the study says.

Water and light

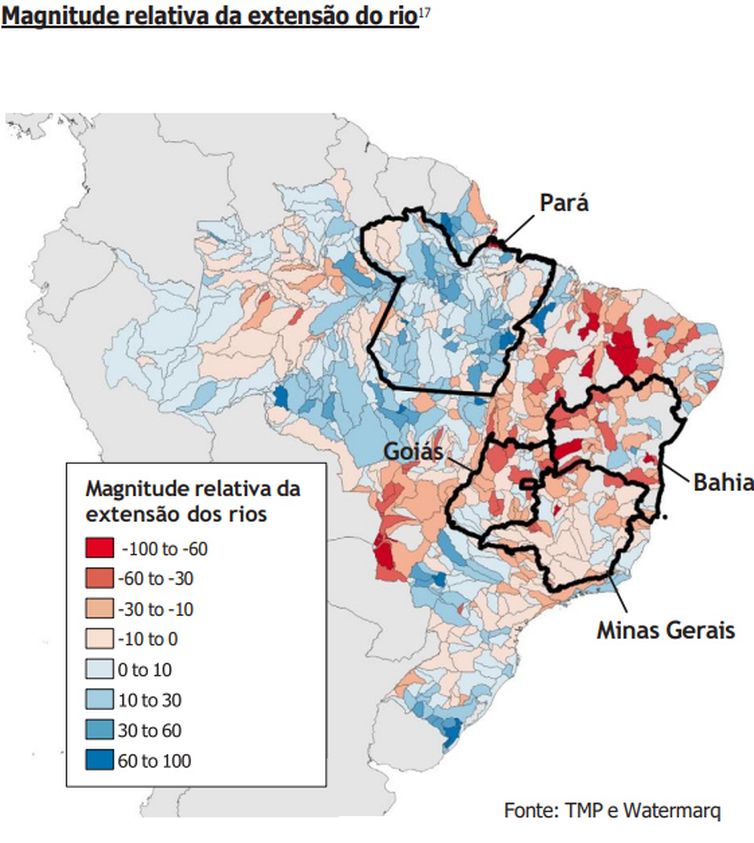

In the evaluation of researchers, intensive use of water by mining should aggravate the scarcity of watersheds. “The extension of the rivers has already diminished in much of Minas Gerais, Goiás and Bahia, pointing to the reduction of water availability and the increase of competition for resources,” says the survey.

As most part of Brazilian energy comes from hydroelectric energy, research considers that mining can impair the supply of electricity in Brazil.

“Steel and mining use disproportionate amount of electricity, consuming about 11% of national production in 2021, although they contributed only about 3% of GDP only [Produto Interno Bruto]”He added.

Hydrological analysis of the study revealed that from 32% to 39% of the sub-basins of Minas Gerais, Goiás and Bahia recorded a decline in the extension of rivers at a level considered “high risk” (ie a decline of more than 10%), between the late 20th and early 21st century.

“This is probably the result of growing water demand due to population growth and associated expansion of industrial activities such as agriculture, power generation (especially hydroelectric) and mining,” the document says.

To

Pará – Headquarters of this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP30) – is the federation unit with the most risks of extreme climate events resulting from the expansion of mining. The state is responsible for about 90% of aluminum production in Brazil.

“While the world is preparing for COP30 in Belém, the race for so -called critical minerals is accelerating the climate crisis in the Amazon,” said Gabriela Sarmet.

Recommendations

The study brings a number of recommendations for governments, surveillance agencies and companies to mitigate the climatic effects caused by the expansion of mining in these four Brazilian states.

“Management of adverse mining impacts will require companies a proactive approach to risk management, solid political structures to ensure effective incentives, robust supervision by the authorities,” the document says.

Maurício Angelo, director of the Mining Observatory, considers that the recommendations will have little effect if the state does not assume its role as inspection of the mineral sector. “It is not reasonable that the state behaves as a partner of the mining companies and gives up its role of being a supervision and regulator of mineral activity,” he added.

Future

In the Jequitinhonha Valley, in Minas Gerais, while awaiting the demarcation of the land occupied today by Pataxó and Pankararu, in Araçuaí, the leadership Cleonice Pankararu, which has three daughters and a granddaughter, fears that the expansion of lithium makes the way of life of indigenous and traditional peoples in the region.

“Our concern is mining because it is going very fast. Environmental licenses in Minas are too loose. It is very easy to take a license to clearers, to mine. And we have a congress that does not support indigenous peoples or the environment. And then mining advances,” he lamented.