A colleague travels to Lanzarote –the easternmost island of the Canary archipelago– and sends me, on her return, some photos of the house where José Saramago lived. I have always admired the Portuguese, famous for his large glasses, his bitter and disbelieving prose, his reflective atheism and his fervor, scarred by old age, for the communist utopia.

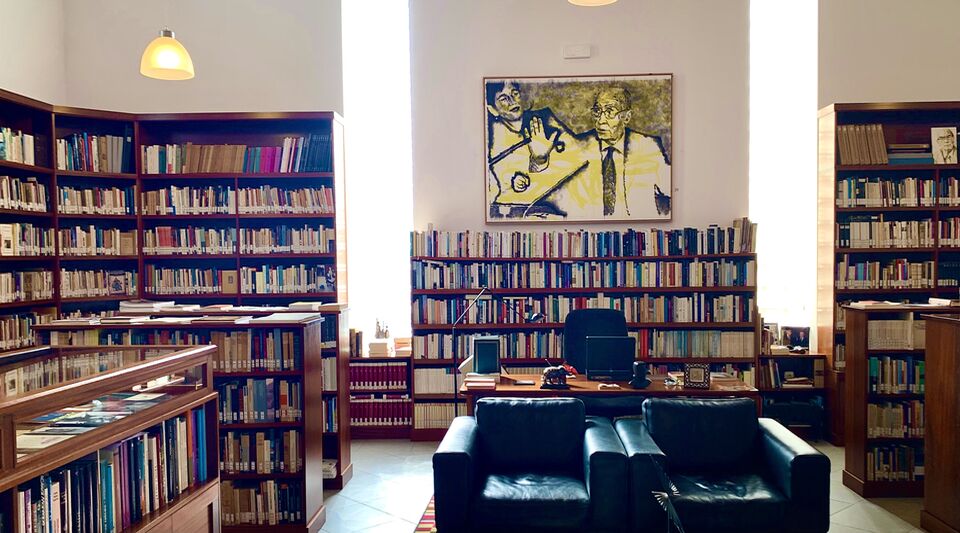

The house that I see in the photographs, of course, is not that of a proletarian, but that of a successful and prosperous novelist. He deserves it, no doubt. He earned it with writing, not with almsgiving and government flattery. Beautiful inkwells on a shelf, portraits of friends, the bed in which he died, a small green table where I would like to smoke, palm trees and cacti in the patio and, in the distance, a landscape that he described as “dark, covered with pieces of of crushed lava”.

And books. Many books. Legions of volumes that now rest on the seats and shelves. Titles in various languages and from multiple cultures. Volumes of a writer who traveled, dreamed and fabled intensely, since one should not live, dream and fable any other way.

A few days ago – on November 16 – Saramago would have turned one hundred years old. Few remembered him in Cuba, a rough and also volcanic island like Lanzarote, where the novelist was welcomed until he famously uttered, and to Castro’s mortification, that “I’ve come this far.”

I understand that they hung some posters in the National Library and that the usual gang met to formalize the burial. Saramago donated the rights to his works to an island that ended up shooting, to its horror, the Cubans who in 2003 tried to leave our oppressive stone raft.

“The bad thing about the islands,” the lucid Portuguese had written a couple of years before, “is when they start to imitate the sea that surrounds them. Fenced, they fence.”

“The bad thing about the islands”, the lucid Portuguese had written a couple of years before, “is when they start to imitate the sea that surrounds them. Fenced, fenced off”

Among the photographs is one of Saramago’s nightstand. Under his glasses, now permanently closed, there is a copy of the Lanzarote Notebooks. They are his diaries from 1993 to 1997, the date on which he abandoned them due to boredom or overwork. The following year and after a long wait, the Swedes awarded him the Nobel Prize for Literature.

It is a hectic decade: the end of the century. In the classic edition of Alfaguara that I have in my hands, the Notebooks they reflect on the hypocrisy of Diana of Wales and Teresa of Calcutta, the ridicule of Gorbachev acting in a pizza commercial and the failure of the communist project; transcribe letters from believers enraged by The Gospel according to Jesus Christ and realize how it was written Essay on blindness; in them, Saramago is intimate, courteous, ironic and endearing, as if he were conversing at the little green table in his patio in Lanzarote.

And of course, there are abundant references to Cuba, to Roberto Fernández Retamar –the gray eminence of Casa de las Américas–, to Cabrera Infante, to the Castro-Guevara tandem, and to the Creole version of socialism during its Special Period.

In May 1993, the young poet Almelio Calderón – now in exile – sent her a letter written in pencil. “Our editorial policy is very slow. Right now there is a big crisis with paper,” he tells her, before nervously admitting: “There isn’t.” Fueled by a hope in the change that was not, the boy without a pen concludes by saying: “Historical moments are being lived here, very unique, very important, very intense, which I hope history knows how to receive in its pages.”

I keep browsing. On January 5, 1994, a trip to the island was aborted, which he interprets as “the last chance to return to the socialist Cuba that I respect and admire.” At the end of that year, he was still promising to defend Castro over Clinton.

Feel the possible novel as a mandate from the deceased. “Matías Pérez, who are you?” He scores several times in Lanzarote, in Lisbon, in Madrid or in Rio de Janeiro

The deepest bond of Notebooks with Cuba is the obsession that seized him when reading the beautiful sampler of the worldby Eliseo Diego. In 1993, Eliseo – “one of the great poets of this century, and I said it inside and outside of Cuba,” notes Saramago – had just won the Juan Rulfo Prize. Soon after, death came knocking on his “modest door.”

Distressed by the friendship that was not, the novelist retires to his library to leaf through Eliseo’s complete poetry. And behold, a discovery is made: “Matías Pérez” –proclaims a well-known passage from the Cuban, which sounds like an incantation to him– “toldero by profession, what was there in the immense airs that you went for them, Portuguese, with such elegance and rush”.

Feel the possible novel as a mandate from the deceased. “Matías Pérez, who are you?” He writes down several times in Lanzarote, in Lisbon, in Madrid or in Rio de Janeiro. He dreams of the hot air balloon, he investigates – “he wanted to know the how and when of such an appetizing story” – and he writes to Retamar begging him for a clue, a silhouette of the Portuguese man who disappeared on the rooftops of Havana. “Who knows if I won’t go to Cuba to discover the mystery of Matías Pérez” Or if I won’t have to invent him from head to toe? “He points out, and gives up.

The end of the story is, I’m sorry, very unromantic. The sinister Retamar responds years later with a letter. Inside the envelope, well folded, there is a newspaper article about Matías Pérez almost in a forensic tone, which ends like this: “The military authorities of the time carried out an investigation that they described as meticulous. There was no sign. Months later they found themselves in some the keys near the Isle of Pines the remains of a balloon”.

Saramago must have dismembered the clipping, who knows if dictated by Commissioner Retamar to discourage the writing of that story, the Havana novel that José Saramago could have written. Retamar, like Mefistófeles, later came to claim the favor: in exchange for the newspaper, he needed a “brief portrait” of Guevara for his magazine.

On July 2, 1996, in his library in Lanzarote, Saramago mentioned Matías Pérez for the last time: “If I have time and I don’t lack courage, maybe one day I’ll go looking for him.”

________________________

Collaborate with our work:

The team of 14ymedio He is committed to doing serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for accompanying us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time becoming a member of our newspaper. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.