It is to the rhythm of forró that the streets of São Miguel Paulista will celebrate carnival in São Paulo this Tuesday (21). A neighborhood located on the extreme east side of São Paulo, São Miguel Paulista is a northeastern stronghold and, during the biggest Brazilian cultural festival, it does not fail to show its roots to the city that welcomed them.

It was in this neighborhood that, in 2012, the Bloco do Baião emerged, a tribute to the centenary of the great Brazilian accordion master, Luiz Gonzaga. The Bloco do Baião is one of almost 500 carnival blocks that will parade through the capital of São Paulo between pre-Carnival and post-Carnival. Most of these blocks pass through the center of the city, but despite the lower investment, there is also revelry going on in the outskirts of São Paulo. In the east zone, for example, 68 blocks will pass, eight of them only in the subprefecture of São Miguel Paulista.

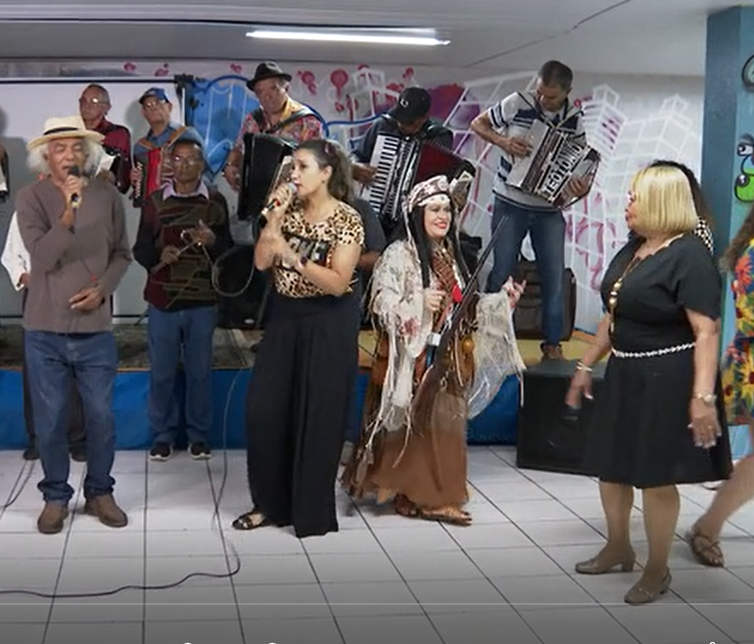

The Bloco do Baião was created to represent and celebrate the northeastern popular tradition. Every year, he leaves in a procession with accordion players, zabumb players, triangle players, fiddle players and a front wing formed by Lampião and Maria Bonita. “Forró is a sequence of Northeastern rhythms. Within it there is the xote, the xaxado, the baião, the coco, the drag-pé. And that is the Baião Block. It was a way of not letting this culture end, of not letting this tradition end”, explained Wagner Ufracker da Silva, better known as Zé da Lua, founder of Bloco do Baião.

“The residents here [de São Miguel Paulista], for the most part, cannot afford to go to the Sambadrome. So here we have blocks with a very large diversity. The Baião Block represents Northeastern culture. There’s the block of sertanejos, of Afro-Brazilian culture, of samba”, he details. “Here in São Miguel Paulista, for example, we don’t have entertainment venues like in other places in the city. It is very lacking. So we do a Carnival aimed at the family and the kids”.

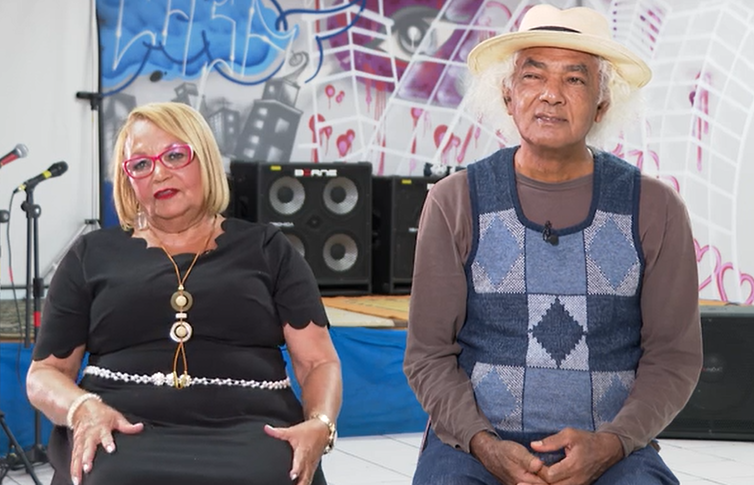

This year, the block will honor two masters of culture in the neighborhood: Sacha Arcanjo and Alzira Viana, who founded Praça do Forró and also helped create the Bloco do Baião.

“My father was a forrozeiro. Where he went, he took me. At the age of five I was already into forró”, said Alzira, in an interview with TV Brazil. “Forró had already dominated my head, there was no turning back. He got it in the blood, ”he says.

“We put on a drag-pé there, a xote, which people really enjoy, and you can do the same magic as in Carnival. And we are with the Bloco do Baião doing this”, said Sacha.

Alzira points out that forró is really a rhythm that people fall in love with. “Forró was not born to die, but to stay. Forró is life. Only those who dance and play can know”, she points out.

Cultural diversity

The outskirts of São Paulo show that the Brazilian carnival is not just made up of marchinhas, samba or axé music. There is room for every rhythm, every kind of party, every kind of manifestation. This is also the case of the Bloco Afro É Di Santo, which runs through the streets of M´Boi Mirim, in the south zone of São Paulo. Founded in 2010, the block is based on samba-reggae and Afro-Brazilian rhythms.

“This year, our theme is Águas de Axé in the Caminhos do Bloco Afro É Di Santo. Our block has two patrons: Oxalá and Oxum, who are orixás. One of our characteristics is to bring, to the drums, the rhythms of African matrix religions and, from there, we find ourselves both in our faith and in the rhythm. From our ancestry, from what we are and what we do in the territory, we are singing and resisting against all this violence that we have suffered and have been suffering over time”, said Andrea Souza de Oliveira, co-founder of the block.

The procession runs through the streets of M´Boi Mirim always on Carnival Mondays. “We are a peripheral affirmative block, an Afro block. This is the Bloco Afro É Di Santo, with this Afro-Brazilian identity and which is influenced by samba and reggae, inspired by the blocks of Salvador, in the terreiro touches and in the awareness of black affirmation and anti-racist culture”, described Mestre Rabi Batuqueiro, founder of the group.

“The people we invited to be part of the block also come from this cultural milieu, from the culture that uses the streets to manifest itself, to show what we do, where we come from. The street is our place of expression”, said Mestre Rabi.

Decentralization

The street carnival is a democratic party and, in São Paulo, it has also moved towards being decentralized, expanding the idea of occupying the city.

Of the 475 blocks scheduled to parade this year at Rua de São Paulo’s carnival, 123 will take place on the outskirts of the city, informed the Municipal Secretary of Culture. City Hall expects around 300,000 people to attend the peripheral carnival. This forecast, informed the secretariat, disregards the central region, Vila Mariana and Pinheiros, neighborhoods that currently concentrate most of the city’s blocks.

“Among the parades on the outskirts are blocks in Itaquera, Grajaú, São Miguel Paulista, Sapopemba, Brasilândia, Pirituba, Guaianases, M’Boi Mirim, Cidade Tiradentes and Ermelino Matarazzo. While the center concentrates megablocks, the peripheral neighborhoods have a greater number of small and regional blocks”, informed the secretariat, through a note.

The street carnival has always existed in the most peripheral communities of the city. But it has gained momentum in recent years, with the emergence of new blocks and forms of celebration. “Carnival blocks have always existed in the peripheries, but it is a fact that in the last 10 or 15 years, the presence of these blocks in the periphery neighborhoods has increased a lot”, said Tiaraju Pablo D´Andrea, professor at the University of São Paulo (USP) and from the Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp) and coordinator of the Center for Peripheral Studies.

In an interview with TV Brasil, he pointed out three main hypotheses for this growth of the peripheral Carnival. One of them, he said, is what he calls the “peripheral cultural spring”, with the proliferation of cultural and artistic collectives in the outskirts of São Paulo. A second hypothesis, he says, is related to popular and social movements occupying public spaces. And, finally, he highlights the fact that the samba schools are no longer able to unite the mass that wants to enjoy Carnival. “Sometimes samba schools have a slightly more rigid format. It’s a competition or you need to pay for fantasy or you need to be assiduity in rehearsals. Therefore, the population, in general, ends up preferring something lighter, uncommitted and without the need to pay for costumes”, he said.

A characteristic of this carnival, he pointed out, is that it is more heterogeneous, a way of expressing the diverse cultural roots of the population that lives far from the center. “It is on the periphery that the Brazilian working class lives, the most impoverished population from the cultural point of view or social relations, and it is on the periphery that there is a certain interculturality, a heterogeneity in terms of cultural roots. This is expressed in the way the peripheries show their culture and, at Carnival, this would not be different”, he concludes.

“São Miguel Paulista is an eminently northeastern neighborhood and it is obvious that, in one of its carnival expressions, it would claim this origin, this musicality that comes from the Brazilian Northeast. The south zone of São Paulo has a very evident black presence, which is also expressed in the defense of African traditions and origins. It is also worth highlighting other demands that have been made through carnival: there are blocks that defend the so-called traditional culture, blocks that defend indigenous culture and blocks that will want to sing what people like to hear. So we’re going to have a carnival block that sings country music, which is very popular in the peripheries. We are seeing that, through Carnival, a series of tastes and musical forms are being expressed”, said the professor.

*In collaboration with Priscila Kerche and Thiago Padovan, from TV Brazil