Imagine being in a city in Venezuela, 9,600 kilometers from Ukrainetrying to inform you about a war you don’t fully understand, and you turn on the TV to watch the state channel.

So, local journalists and reports from foreign media affiliated with Moscow describe the conflict according to the vision of one actor: Russia.

They do not speak of war or armed occupation or invasion, but of “special operation”. Nor do they describe scenes lived in the Ukrainian terrain attacked.

Instead, they speak of a Ukrainian government full of authoritarian “neo-Nazis”, supposedly willing to use weapons of mass destruction, while drawing an altruistic Moscow, whose primary aspiration is to liberate that population from oppression.

There are plenty of statements from officials in the government of President Vladimir Putin, but there are few or none about the Ukrainian authorities, unless it is news that tarnishes their reputations and intentions.

“Russia attacks mercenary training center in Ukraine. Russia delivers more than 4,100 tons of humanitarian aid to Ukraine. Russia denounces that Ukrainian neo-Nazis kill civilians in Mariupol on a daily basis. Headlines like these also abound in the digital version of the Venezuelan state channel VTV.

The use of euphemisms, the exclusive quotations of Vladimir Putin and its officials, and an “absolute” replication of the Kremlin’s narrative characterize the coverage carried out by the media of the Venezuelan State and others related to the armed aggression against Ukraine, experts say.

The media financed by the government of Nicolás Maduro, such as Venezolana de Televisión and Telesur, are “completely aligned with the communication codes of the Kremlin,” warns León Hernández, a university professor, researcher and director of the Venezuelan Fake News Observatory.

Hernández, author of books on journalism and communication in Venezuela, explains that the press near the Miraflores Palace, epicenter of political power, adopted the use of terms that usually characterize Russian rhetoric regarding war.

“They talk about the supposed regime of Ukraine, when it is a government elected in a democratic system. They speak of a supposed threat from the NATO to justify the operation. Here, they replicate it with all their vigor”, he exposes.

The word “operation” or the term “complex conflict” displace other valid ones in the state news, which better describe what happened on Ukrainian soil, such as “invasion”, Hernández details to the Voice of America.

“They are reiterative in the main message that the Vladimir Putin regime has used to say that the Ukrainians must surrender because they have been kidnapped by a cabal of neo-Nazis. That is the constant,” he assures.

Restricted offer

The supply of independent press in Venezuela has been “restricted” for years, explains Carlos Correa, a Venezuelan researcher and director of Espacio Público, a civil organization that promotes the rights to freedom of expression, information and social responsibility of the media in his country.

In television, in 2007 the State withdrew the concession of one of the most watched private channels, Radio Caracas Television. Since 2004, a Social Responsibility Law promoted self-censorship in radio and television stations.

Also, the state monopoly for the distribution of newsprint caused, through the discretionary allocation or restriction of this raw material, the progressive closure of dozens of written press media with regional and national circulation.

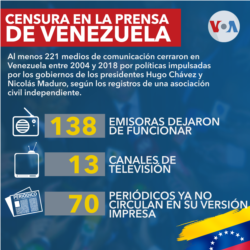

According to Espacio Público, 221 media outlets were closed in Venezuela between 2004 and 2018 due to some form of official censorship. Among them are 138 radio stations, 13 television channels and 70 newspapers that no longer circulate in print.

“If you have a restricted offer, of course, you don’t have many options and you can have a greater preponderance, the impact options increase” with transmissions of “biased” information in state media, says Correa in conversation with the voice of america from Caracas.

The specialist and human rights defender assures that the State media “ecosystem” also includes officials who use their social networks with “a kind of parallel spokesperson” about the war in Ukraine.

“Clearly, they are within the logic of fake news. There is also biased coverage based on Russia’s interests. It is a perspective aligned with the objectives of Russian propaganda”, says Correa.

On March 6, Maduro’s communications deputy minister, Alfred Nazareth, criticized the European censorship of media financed by the Russian government, such as Sputnik and RT, which are usually references in Venezuelan media.

“Hundreds of thousands of users on TikTok become disseminators of reality in Ukraine: the Dombas massacre perpetrated by the Nazis and silenced in the Western (sic) media comes to light. Poetic revenge! ”, He then wrote on his Twitter account, @luchaalmada.

subtle changes

The Maduro government has manifested in recent weeks “subtle changes” in its discourse on the war, despite its persistence in describing Russia as a victim of NATO, observes Geoff Ramsey, director for Venezuela of the think tank Washington Office for Latin America (WOLA).

“While keeping that rhetoric aligned with the Russian version of the conflict in Ukraine, the Maduro government has offered to mediate. He has put more emphasis on the need for a peace dialogue”, he expresses to the Voice of America.

Ramsey believes that this new position would correspond to “a dynamic where Maduro is seeing how much it could benefit him to distance himself from Moscow.”

That nuance about the war coincides with Maduro’s meeting, in early March, with a group of senior officials from the government of US President Joe Biden, including Ambassador James Story.

The meeting occurred at a time when the Chevron company is lobbying in Washington in order to relax sanctions against Maduro and his oil industry to supply Russian crude, vetoed by Biden, with Venezuelan crude.

Two days after Maduro meeting With US spokesmen, the president publicly advocated a dialogue between Russia and Ukraine to settle the confrontation.

“Venezuela adds its voice to peace, to dialogue, to resolutions through peaceful mechanisms. They will never see us in the ranks of the war itself, or because of the war,” the president said during a congress of his party, the PSUV.

In the same speech, he hoped for the reactivation of the dialogue with the Venezuelan opposition, detained in Mexico City since October of last year. “If we ask Ukraine and Russia for dialogue, we have to set an example,” he said.

Caracas and Moscow strengthened their energy, military and geopolitical relations since the strengthening of sanctions by former President Donald Trump, between 2017 and 2019, recalls the WOLA director for Venezuela.

Those links have permeated the communicational, he notes. She considers that the ignorance of a reality as distant as the Ukrainian one gives Maduro a window to offer a version “more disconnected from reality”.

“Perhaps in Venezuela there is not much deep knowledge about Ukraine and that allows the Maduro government to lie even more to its own population,” he says.

Correa, from Espacio Público, also says he has noticed “a change, a certain rearrangement” of the Maduro government in the face of the armed conflict in Ukraine after the visit of spokesmen for the State Department and the Biden administration.

“There was like a certain change in the line on the part of the government. It is talking less about the subject. Later, Maduro has not insisted on the issue. As for the coverage (in state media), they feel very watched”, he maintains.

Ramsey, for his part, assumes that the Venezuelan government offers Moscow its propaganda channels to amplify the messages of the Putin government. “That corresponds to the geopolitical alliances between the two countries,” he adds.

The Kremlin, he points out, tries to paint itself as a “victim of Western aggression”, exaggerates the risk of a “neo-Nazi right” in Ukraine and often describes the war as a “humanitarian operation” aimed at protecting the local population.

“We see a clear attempt to hide the truth about possible crimes against humanity and attacks on civilian targets such as hospitals. We have seen all kinds of propaganda from the official Russian media, ”she remarks.

relative influence

Venezuelan television “is not a favorite place” to get information and the state channel Venezolana de Televisión is not a reference in that sense, clarifies the director of Espacio Público. Nearly 50% of local users identify VTV as a pro-official media outlet, according to a survey by the firm Datanalisis.

“It is not among the top 10 media outlets with the greatest impact (on society). People know that they are going to get official information there, either to reaffirm their vision or try to contrast it,” says Correa. The priorities to achieve moderately plural information are social networks and the Internet, she says.

The purchases of newspapers and channels by businessmen close to Chavismo and the blocking of pages of digital newspapers critical of the ruling party, such as the whistle, The National, The Pin and Cocuyo effecthinder that collective intention to see news with more journalistic than propagandistic features.

Hernández, from the Venezuelan Fake News Observatory, is not so convinced that state media do not have enough impact on society. He believes, on the contrary, that they have “a greater reach” than the independent press.

Censorship and self-censorship for years in Venezuela have reached “a very great influence” while digital media do not have “such a powerful reach,” says the author of the book The censored screen: RCTV, Globovisión.

“Of course they have influence and relativize the truth. They join other fake news and disinformation units that have overwhelmed the digital ecosystem in this first important military confrontation. It is difficult for this viralization of false content not to penetrate a population uninformed by the restrictions and censorship imposed since the beginning” of Chavismo, he affirms.

Correa, for his part, agrees that “the basic rules of propaganda” prevail in the circulation of news through official media.

“There is a certain exhaustion of the verification logic. VTV is basically a propaganda tool” in Venezuela, he said. He believes that the country has been migrating for years to other platforms that allow him to obtain more appropriate information and circumvent official censorship.

He cites the spontaneous demonstrations of July 2021 in Cuba and the Arab Spring between 2010 and 2012 to underline how, in Venezuela, free information circulates equally in the midst of a society “closed” by official restriction.

Correa is clear about his explanation: “it is a dynamic of resistance”.

Connect with the Voice of America! Subscribe to our channel Youtube and turn on notifications, or follow us on social media: Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.