It’s ten forty in the morning. Roger Ruiz Torres, 53, speaks in front of a microphone for the umpteenth time in seven days. He is standing in front of the Dirincrithe same building where the police officers in charge of investigating crimes work. One of them left him without his firstborn.

listen to the newsText converted to audio

Artificial intelligence

“I call it the damn call,” he says.

WE RECOMMEND YOU

STATE OF EMERGENCY AND WE HAD BEEN T3RRUQU34D0 SO MUCH | WITHOUT SCRIPT WITH ROSA MARÍA PALACIOS

Exactly a week ago, that call tore him away from the life he knew: work in his taxi, lunches with his boys, visits from his grandson. Since then he is no longer an ordinary father. He is the man who gives interviews. “I had never spoken in front of cameras. It is terrible to become known for the death of a child,” he repeats. Today he has more than twenty.

Before October 15, Roger was an amateur soccer player, ex-military man, neighborhood man and proud grandfather. He had raised Mauricio and Fabio with the same discipline that he learned in the Army.

The police officers who were part of the team accused of killing him belong to the Kidnapping Division. His task was to save people from death, not to kill.

The shot

On October 15, at 11:12 at night, a shot pierced the body of Eduardo Mauricio Ruiz Sanz32-year-old rapper known as Trvko. The event was recorded on video by this reporter. You hear the flash, a scream, the body falling. In the midst of the chaos, his brother Fabio picked him up and, helped by protesters, put him on a motorcycle heading to Loayza Hospital. He arrived lifeless.

At 11:30 pm, Roger received the call. “They told me that my son had been shot. I didn’t think he would die,” he tells me. “I ran to Loayza. First I got to my door and went back to my room. I said: I hope it’s a bad dream. Then I just came out. I said: Oh my God, please, no… not my son.”

Past moments of peace and family happiness, before the fateful October 15. Photo: courtesy.

At five in the morning on October 16, he returned home. He had to tell his mother, Mrs. Otilia, that her grandson was dead. She saw him enter with a lost look and understood without hearing him. He burst into tears.

A few hours before the shot, the day had been ordinary. “It was before lunch, I think… I don’t remember precisely,” says Roger. “I told him: ‘Son, I already have tickets to go to the stadium’. He said: ‘Thank you, dad, then tomorrow we’ll go.’ Lima Alliance vs. Sport Boys, scheduled for Thursday the 16th. He, his two children and his grandson would go, all blue and white fans. That family plan was suspended forever.

Hours later, the country was preparing for another day of protests. Nobody in his house imagined what was to come.

the mass

On Wednesday, October 22, the family gathered at the La Merced temple. It’s twelve forty in the afternoon. Mrs. Otilia, eighty-nine years old, occupies the third bench. Every time he hears the name of the one he raised like a son, he bursts into tears. “Let us pray for the eternal rest of Mauricio. They can go in peace,” says the priest. But peace is what the family has the least.

Otilia looks up, presses the handkerchief to her face. He doesn’t want to talk to the press, but when Roger tells him that we have been with him since the morning and that I recorded the first video of his grandson’s death, he stares at us and sadly thanks us. He squeezes my hand tightly. It is the same gesture with which, once, he had to console Mauricio and now he must do it with his great-grandson, Max, 10 years old.

“From a very young age I have taken care of him,” he whispers, “also of his little son, because they were a young couple when they had him. They told me that he had two genius grandchildren, very talented. I’m only going to find peace when I close my eyes, when I’m gone.”

“They told me that my son had been shot. I didn’t think he would die,” says Roger Ruiz. Photo: The Republic.

The team

According to documentation accessed The Republicthe Dirincri operational team deployed that night was made up of five members: Lieutenant Walter Andy Segura Montañez, group leader, and non-commissioned officers Roberto Carlos Martínez Román, Luis Michael Magallanes Gaviria, Kendy Antonio Granados Soto and Omar Raúl Saavedra Bautista.

The letter detailed that they had to participate “with work clothes and characteristic Dirincri PNP vest, without weapons”, in intelligence work, maintenance of public order and vehicle intervention and control. However, security cameras from the Municipality of Lima show two plainclothes officers, with weapons in their hands. One shoots into the air. The other’s bullet ended up in Mauricio’s body.

Hours later, the commanding general Oscar Arriola reported that the shot that killed Trvko it would have come from the weapon of non-commissioned officer Luis Magallanes Gaviria, of the Kidnapping Division. But witnesses support another version. Magallanes said he lost his gun that night. The evidence of the crime never appeared.

The insult

Days later, while the country was discussing the events, the president of Congress, Fernando Rospigliosidistorted the young man’s stage name and called him “Terruco.” He did it in a plenary session, live, and he repeated it even after his advisors warned him of the error and wrote to him in large letters, on a “trick” piece of paper, so that it could be corrected.

Another congressman, Alejandro Aguinaga, involved in the case of forced sterilizations during the Fujimori dictatorship, supported him and called him an “urban terrorist.”

Roger then decided to defend not only justice, but also honor. He walks with a folder under his arm. Inside there is a notarized letter addressed to Rospigliosi. “I demand that the statement and misrepresentation of information expressed by you be rectified within 24 hours, which constitutes aggravated defamation and causes damage to my son’s good memory,” the document reads.

Mauricio Ruiz took the pseudonym Kurt, for Kurt Cobainback in 2008. To cover the expenses of his musical trips, he dedicated himself to juggling at traffic lights. Then, his friends reversed the nickname to Truk, because of the “tricks” he did. Then they called him Truquito. Finally, Trvko remained. His brother Snap, who was his music producer and stage partner, had to tell the story in a public conference to defend someone who is no longer here, but continues to be attacked.

Mauricio discovered his artistic talent at an early age, his father remembers. Photo: courtesy.

The other children of the country

As he walks, three people approach him. Among them is Wilfredo Huertas Vidal. They didn’t know each other, but they recognized him from television and gave him strength. Huertas tells him that he spent five days in detention after the march, that during the intervention they stole his cell phones, that they beat him and that they told him that they were going to kill him. Roger listens to him carefully. Since the death of his son he has involuntarily become a spokesperson for those who survived the repression.

In the videos recorded that night, Trvko is seen running to help Luis Reyes Rodríguez, ‘Flipown’, when he fell after the impact of a tear gas bomb. They did not know each other, but the musician instinctively approached to help his colleague. Days later, Roger spoke with Reyes’ mother.

“I recently spoke with Luis’s mother,” he says. tear gas bomb It hit him in the head. He is in Loayza, in an induced coma. Her mother told me that she no longer has money, that she is very complicated. Poor thing, at least I have my family; “She doesn’t have anyone.”

Minutes earlier, Roger had received a call from his nephew from France. He gave him his condolences and offered him financial help to continue seeking justice. The bell came at the exact moment. Minutes before, he commented that he was going to make a radical decision: “I’m thinking of selling my car. It’s my work tool. But I don’t know how long I’ll be able to continue affording all this.”

Trvko

Since his death, Roger barely sleeps. “I sleep at times,” he says, “I spend the nights with my mother. Sometimes we wake up in the middle of the morning. She tells me that when I manage to fall asleep, I scream.” A few days ago he went up to the roof to hang his clothes. There was his son’s room. “It scared me a little, but I said, ‘What can my little son do to me? It would be a blessing to meet him, even for a second.'”

The father who stays. One of his classmates is with him today. He was the one who helped him make a flyer to raise funds. “I don’t want them to think that I’m profiting from my son’s death,” says Roger, “but what do I do, I’ve already spent all my savings. Who’s going to look after my grandson now? It’s going to have to be me.”

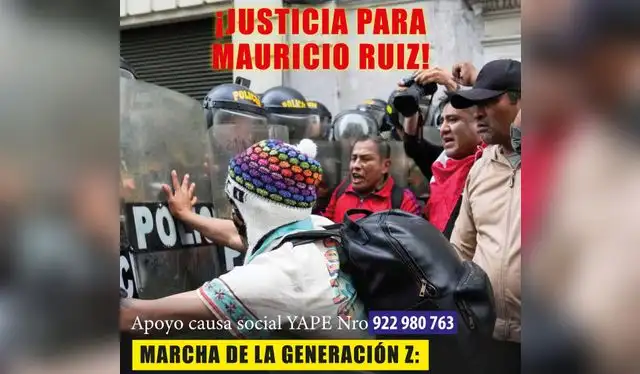

Collectives request financial support for the victim’s family. Seeking justice in Peru is expensive. Photo: diffusion.

Roger says that he could have been a soccer player. He played in the minors for Alianza Lima, he met the Potrillos before the accident at Fokkerbut luck was not on his side. “Then I joined the Army,” he says. There is no nostalgia in his tone, there is history.

When we pass through Plaza Francia, he asks me to take another path. He doesn’t want to walk by where his son fell. “They made me come two days later, but I never plan to stop by here again. I can’t even see the videos of the event. I have taken my son’s paintings out of my house, I have them saved. I can’t see him.”

He remembers Mauricio as a child. He says that he discovered his talent early, that he drew well, but above all he liked to sing. As a teenager he got into hip hop, started writing lyrics, going on stage. Everyone in the neighborhood knew him.

From the day of his death he preserves every gesture. “I saw him leave the house,” he tells me. “He told me he was going with his friends. I wouldn’t have let him go to the demonstration. I know it’s a right, but I was scared because of everything that has happened in these years. If he told me, with some story I would take him somewhere else.”

The country that shoots and lies

Now, a group of young people from the Generation Z has invited him to a press conference. They will announce a new mobilization and among their slogans is the search for justice for Trvko. “If they want to march, that’s fine,” says Roger. “But I’m going to go and ask them not to have violence. That they try to keep everything peaceful. I hope the police do the same. I’m going to tell them that I wouldn’t want any of their parents to receive the call that I received.”

The afternoon falls on the Cercado. Roger walks with the folder in his hand. Inside are the names of those responsible, the evidence accumulated, the notarial letter. In the other she carries her cell phone, where she keeps photos of her son and the messages that she still cannot delete. His mother is waiting for him at home; in his neighborhood, Mauricio’s friends; in the square, the young people who will march again.

Peru continues its routine. But for Roger—and for those who have lost their loved ones—life stopped at 11:12 that night.

Mauricio’s father and grandmother participate in a mass in his memory. Photo: courtesy.