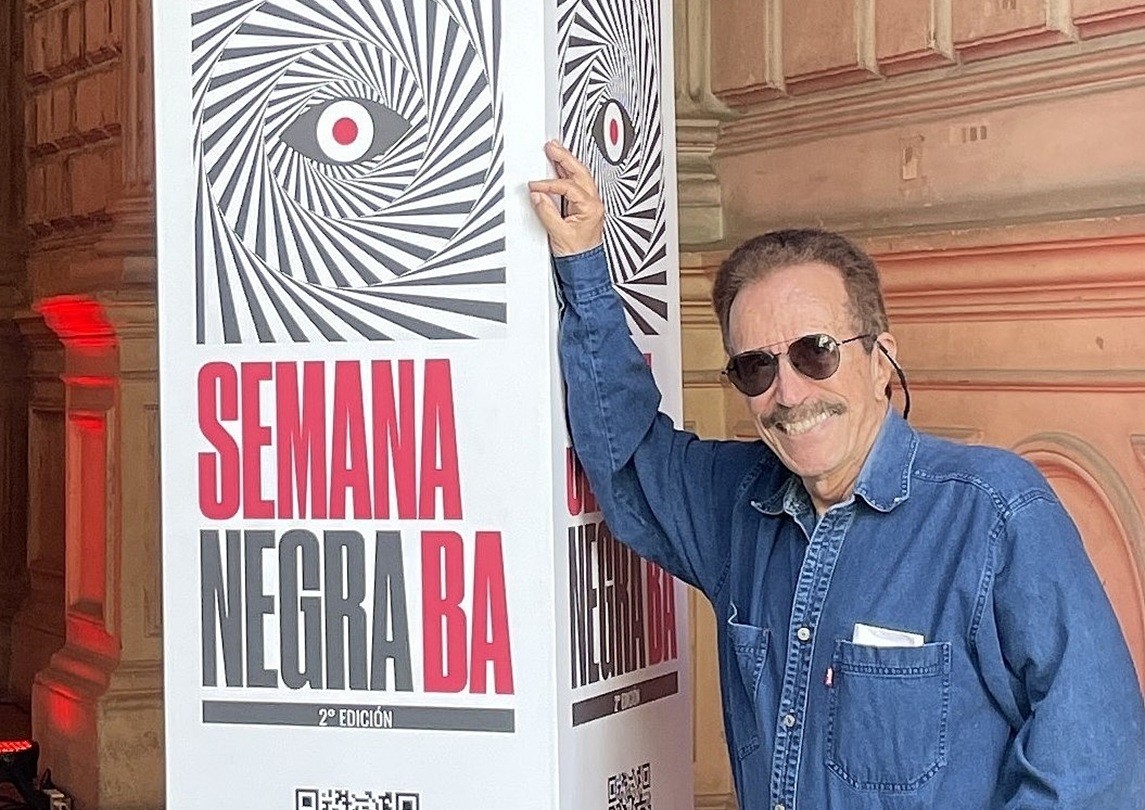

The International Literary Festival on Black Police Genre, Black Week BAallowed me to talk with Rodolfo Pérez Valero (Havana, 1947), a popular writer in the seventies and eighties in Cuba, when detective genre books not only broke sales records, but also made their promoters true stars like those of the cinema.

At least that’s how the Mexican Paco Ignacio Taibo II saw it, witnessing the crowd gathered around La Moderna Poesía during a police literature meeting that took place in Havana in 1986, as Pérez Valero remembers. He has lived in Miami for 30 years but as a Cuban he participated in this meeting promoted by the Ministry of Culture of the City of Buenos Aires.

For Pérez Valero it all began in 1976, when the book It’s not time for ceremonies He won a laurel of significance on the island. The event catapulted him to literary stardom. “When that novel won the prize it overwhelmed me positively, they interviewed me in all the magazines,” he says.

“I think it was entertaining, it didn’t have a pamphlet. But I wasn’t aware of that,” he recalls, and adds a detail that he also considers to be the foundation of the rise and popularity achieved by the literary movement of which he was a part: “Cubans were a captive audience, they did not receive books published abroad. That made us very popular.”

A life as a writer, and a meeting in Havana

Pérez Valero was 26 years old when he wrote the novel where he says, he established the collective hero as a fundamental person. “I finished it in December of ’73, I sent it to the Anniversary of the Revolution contest. I didn’t know if I could write a novel and I only tried to write one. What happened next surprised me.”

The book was published three times in Havana (1974, 1977 and 1979) and crossed borders to reach markets such as Buenos Aires, Puebla, Prague, Bratislava, Moscow, Sofia and kyiv.

Regarding his production, books such as The seven points of the crown of King Tragamas, National Children’s Theater Award The Golden Age 1978; the youth novel Mystery of the Pirate CavesMention by UNEAC in 1979 or Confrontationwritten with Juan Carlos Reloba and recognized today as the first Cuban crime and science fiction novel that was Mentioned in the national crime novel contest on the island in 1983.

At that time he worked as assistant director of the Rita Montaner theater and although he was already a tough writer in the crime genre, it was his status as a children’s writer that allowed him to visit countries such as Czechoslovakia and Bulgaria, where he established a relationship with other promoters of the crime genre, laying the foundations for what would give rise to the Cuba-86 Crime Writers Meeting.

The event achieved greater visibility in the press due to a series of fortuitous events among which Pérez Valero highlights that there was no other relevant event on the island. In those days the magazine was also born Enigma.

The echoes of a memorable publication

“We organized the first issue of the magazine Enigma. It was going to be a special number for that event, but a librarian friend of mine told me: ‘Give it number one, because at the same time as you name it number one, the libraries have to register it.’”

The magazine, coordinated between Pérez Valero and Alberto Molina, and where Ignacio Cárdenas Acuña was publication secretary, was published since June 1986 and had nine issues in which narrators such as Yulián Semiónov, Jean-Patrick Manchette, Manuel Vázquez Montalbán, Juan Sasturain, Luis Rogelio Nogueras and Paco Ignacio Taibo II himself collaborated.

The design corresponded to Lázaro Enríquez and Bladimir González, but from then on artists such as Ernesto Joan and Rafael Morante collaborated. Enigma It was printed in the magazine’s workshops Sea and Fishing and in a Light Industry printing company. It had its last issue in 1988.

“Alberto Molina stayed, and at that time it was not like now, you were a traitor. Threat letters began to reach the UNEAC, where it was said that I was next, and all that. So I only produced the last issue dedicated to Raymond Chandler.”

Pérez Valero is convinced that the magazine helped disseminate Latin American literature and internationalize the work of writers from the region.

During those days, the International Association of Crime Writers (AIEP) was also founded, a group created with the support and initiative of Paco Ignacio Taibo II. The group held meetings in Mexico City and in Yalta, Crimea; in Prague.

“Just when the authorities of that country arrested Václav Havel and the AIEP (which was by chance the only international organization meeting in Prague at that time) issued a statement calling for the freedom of the man who would later become president of that country.”

Also, Pérez Valero points out that the first Black Week in Gijón was conceived as a meeting of the AIEP executive, which would also be a popular fair of police literature. In 1990 Black Week served as another international meeting of the Association.

The policeman in his element, and in the peephole

Although at the beginning from the UNEACc the crime writers themselves were considered “minor writers”, according to Pérez Valero, there had already been a rapprochement since 1979; first with the holding of a colloquium on Police Literature.

“There we met, but it turns out that the largest number of crime writers lived in Guanabacoa, and we joked about that. Alberto Molina, Juan Carlos Reloba, Armando Cristóbal Pérez lived there. We were four of the well-known writers who lived there.

It was around those dates that the UNEAC also asked them to be part of its membership and in this way the subsection of crime writers was established.

“I found out years later that the academics, the foreign Cubanologists who studied literature, when they went to the UNEAC to ask about detective literature, could not give details about us. Those who arrived were attracted to our work, they thought it was a difficult phenomenon for a socialist country; furthermore, if they were Latin Americans they lived under a right-wing dictatorship, they thought that Cuba was a paradise; then, how could there be crime in Cuba?” remember.

But, precisely because of the rise of that narrative, detective literature was viewed with suspicion, because although it enjoyed popularity and there was no shortage of talent among its enthusiasts, it emerged as an opportunity for the cultural apparatus in its intentions to impose socialist realism as an aesthetic, something that the old militants of the Popular Socialist Party (PSP) had attempted since 1959 as soon as they took power in different government structures, before the government itself would have declared its ideology.

In this regard, experts on the subject such as the critic Rafael Grillo have written that “it is not possible to blame Pérez Valero and his It’s Not Time for Ceremonies” for the rise of the police force, already transfigured into a “paradigm” of a “Manichean aesthetic put at the service of an ideologizing intention” and where “good and bad guys were hung at each end, stereotyped and turned into cardboard characters” when Pérez’s own work Valero says “of an acceptable literary spirit.”

The end of one era, the beginning of another

Pérez Valero has won the Gijón Black Week award five times; In one of those, in the nineties and still on the island, he had to give the prize money to Paco Ignacio Taibo II because the possession of dollars was illegal in Cuba.

“The year 89 marks a before and after for the Cuban people, for Cuban literature and for police literature. Until that year the investigators of the Ministry of the Interior were the heroes of the novels, and for the population it was like that. In the year 89 the socialist camp fell and then, the most terrible thing, what happened with Ochoa and the De La Guardia brothers. I stopped writing at that moment. I didn’t write anything new, but I started writing stories for Semana Negra, because dollars were needed.”

For those years they decided to free up a little more and allowed those over forty years of age to leave Cuba, he says, first the limit was sixty years old, until they went lower. “You couldn’t keep promising people a future that never came. I traveled to Miami, I went to New Jersey, where my parents had lived since 1966. When I returned, I told my wife: ‘We’ve been scammed.'”

His wife, who witnessed this interview, was working at the National Library at that time and did not want to leave the country. “But things got so bad that my mother-in-law told her: ‘You have to go’. We had a daughter. In ’95 we arrived in Miami.”

“At that time, just as in Cuba nothing was known about what was said in Miami, in Miami what was done in Cuba was denied. You arrived and you were the last in line. It’s not like now. A good job was any job. My wife had to work in a factory, where she didn’t get sick from nerves because she couldn’t, she had to keep the house. I got a job in a supermarket until one day I managed to get into Telemundo. Later “I came to Univision.”

“In those early days I didn’t write anything. I didn’t write for about ten years. In 2009 I published a love novel that takes place in Cuba, during the Special Period. It’s called Havana-Madrid. I sent it to a contest in Asturias and it won, although the economic crisis came and they didn’t publish it. I continued sending to Black Week, and I won two more times. In 2010 I had a book of short stories published by Penguin Random House in Mexico: A man knocks on the door in the rain.

“I was convinced that my literary career would stop when I left Cuba, but, on the contrary, slowly, over the years, it ended up becoming more international, as shown by my publications and awards in other countries and my participation in several Black Weeks in Gijón, Buenos Aires, the Black Week in Miami and Puerto Negro in Chile.”

The mysterious case of the man who traveled to the south

Paco Ignacio Taibo II himself has called him “the great storyteller of Latin American neo-police,” but in several places you can find curious references not to his literary career, but to his own biography. On Wikipedia it says that in 2001 “due to bizarre life circumstances, the name was changed and, the following year, it was changed again.” In Ecured, the Cuban digital encyclopedia, it is noted that “married several times, this man who modified his face through plastic surgery and years later changed his name.”

“The truth: when I was 19 I had surgery for maxillary prognathism and my face changed. I was born as Rodolfo Alejandro Pérez Valero. When I became a citizen of the United States I became Rodolfo Alejandro Pérez and then I discovered that Rodolfo Pérez Valero no longer existed and was just my pseudonym.”

Pérez Valero wears dark glasses similar to the ones I believe he was wearing in the photo through which I met him many years ago. Then it was part of a book about Cuban writers living on the island in the late 1980s. Our conversation occurred at the Buenos Aires House of Culture, located on Avenida de Mayo and originally headquarters of the newspaper The Press. Nobody carried a weapon. There were no mysteries to solve other than a debt to settle with literature.