Madrid/Rarely does the Spanish press report on the death of a homeless person, but this week it happened. It started in Cádiz and has reached television stations based in Madrid. The deceased was the Cuban Roberto López and before living on the street he was many things: son of Ernesto’s bodyguard Che Guevara, musician with Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez, combatant in Angola, political prisoner in Cuba and exiled in Spain.

He arrived there in 2011, as a result of the release agreement between the Church and the Cuban regime mediated by the Government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. López did not belong to the well-known Group of 75, detained in the Black Spring, but he joined a last group of 11 prisoners led by Néstor Rodríguez Lobaina, president and co-founder of the Cuban Youth Movement for Democracy, declared a prisoner of conscience by Amnesty International. and that he was on a hunger strike at that time.

Since then he lived in Cádiz. “I came to Spain because I was given subsidiary protection and international protection. We were guaranteed housing and money for four years. But I never received anything,” López had told the press.

“I came to Spain because I was given subsidiary protection and international protection. We were guaranteed housing and money for four years. But I never received anything.”

According to the medium The digital voice, Roberto had addressed different organizations, but never received a response. Health problems came: pneumonia, pneumonia, a broken hip, pain in one leg… He went to Santiago de Compostela and Huelva, but ended up returning to Cádiz, where he earned a living teaching music, until that alcoholism was slowly destroying him.

“A professional musician, he was left in a state of absolute precariousness,” said Miki Carrera, spokesperson for the Nadie Sin Hogar association, which sporadically attended to the musician. The NGO called for a tribute in his memory at the doors of Cádiz City Hall on April 7, one day after the Puerta del Mar Hospital certified his death due to complications from a foot injury.

After the pandemic, when he had already sold all his musical instruments, he lived for a while in a vehicle that got him the Association of Homeless People with Rights (PESHO-DE). “Inside him he had a cot to sleep on and his few belongings. For him it was a palace,” Milagros Fernández Bey, one of the people closest to the Cuban in recent times, tells television.

When he was not protected, Roberto López was afraid. “More than one kicked him,” laments Fernández Bey, from PESHO-DE, who accompanied the Cuban for the last year trying to rescue him from the situation in which he found himself.

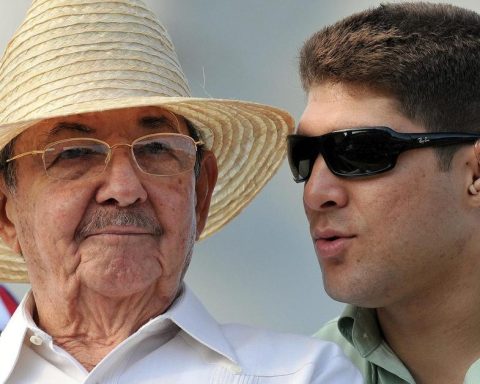

“We Cubans are of a different kind,” he used to say, according to an emotional farewell text that his friends have published on social networks. When he was a child he played with Guevara’s children, because of his father’s work, who was part of his security team. Fernández Bey affirms that López had told him that Fidel Castro himself separated him from his father, whom he left for dead for five years. Until one day they asked him to go to a government building, they told him not to be scared and, when he opened a door, his father appeared. “I told the anecdote through tears,” he says of the incident.

Fernández Bey affirms that López had told him that Fidel Castro himself separated him from his father, whom he left for dead for five years.

Although he trained to be a refrigeration engineer, his music studies caught him and led him to share the stage with several members of the new Cuban trova, including Pablo Milanés and Silvio Rodríguez, but he ended up going to Angola as a combatant.

“I’m not a snitch. Before revealing our positions they had to kill me,” said the artist, who in 1982 ended up joining the Cuban opposition and going to prison for being considered “anti-Castro.” There he spent ten years, which, however, seemed more tolerable than the detoxification center where he was in Cádiz.

“Once I asked him how he had been able to endure ten years in a Cuban prison, who knows what that’s like, and not endure the discipline of addiction treatment. “He told me that in prison you earn your place and the respect of the guards, but that in the treatment centers he could not tolerate the humiliation and undignified treatment to which they subject you,” says José, also from the NGO that assisted him.

“Perhaps – he wonders – these are measures that should be considered changing, because they are therapeutic, rehabilitation and reintegration centers. Measures that do not consist of ‘at the slightest chance, you’ll go out on the street’, because there is more tolerance in daycare centers. It is clear that the dignity of a human being is as far as he can endure. Perhaps Roberto’s fell to the minimum, suffering the inclemencies of life on the street and the lack of humanity.”