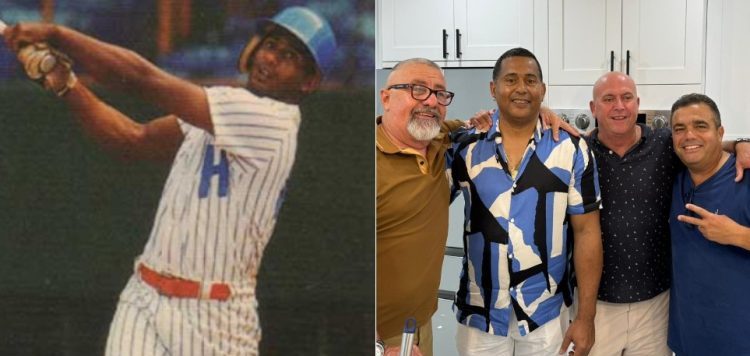

HAVANA, Cuba.- Roberto Colina ran with a certain amount of stiffness inherited from the gym. That is the first image that comes to my mind now that I begin to write this interview with the formidable first baseman of Industrialists in the eighties and nineties of the last century.

Like the immense Orestes KindelanHe wore the number ’46’ and hit the ball with the ferocity of a killer. At first he did his job with singular elegance, and the infielders who surrounded him recounted that they threw to the base with the certainty that he would pick up the hit.

At that time I saw the National Series and he was a rabid Industrialist. So I have that scene of the last out of the 1991-1992 championship fixed in my retina: rolling to third, the throw to first and Colina, excited, throwing the ball to the skies of the stadium.

And also that other one about (I think) the best day of his sporting life, when he swept Villa Clara to the tune of two doubles and two home runs in the third game of the decisive playoff in 1996.

He was a star in an era where it was difficult to be one. His numbers in Cuba speak of an average of .293 in 11 series, with an OPS of .882 and an admirable walks/strikeouts ratio of 519/460. Meanwhile, in the field he averaged .992 with almost 700 participations in double plays.

Colina was definitely up to the task of the uniform he wore. That uniform he still speaks of with immense pride, to the point of considering it “a privilege”: “I feel happy to play with Industriales and to have been in teams that were a school. I can say that I had the honor of being part of a team full of stars and playing with people like Augustin Marquetti and Pedro Medina. I started out at Metropolitanos, but playing for Industriales seems like a privilege to me.”

—What was it like to be a player for the Blues?

—Playing against Industriales was a dream. It’s a team that people love and hate, that a lot of people follow all over the country. Wherever we went to play, there was a full stadium. The same in the capital as outside it, always a full stadium. There was a rivalry in which everyone wanted to beat Industriales. For the other teams, beating us was a feat.

Playing with Industriales is like playing in the United States with the Yankees. Each stage has its merit, the current Industriales also have the responsibility to win, and this year we saw how they came back from a 0-3 deficit against Santiago de Cuba. But the results are hard to see because of the emigrationthat every time a good baseball player comes out, he wants to go out and test himself in the best baseball in the world.

—What were your greatest strengths in baseball?

—One of my greatest virtues, possibly the greatest, was defense. In my early years I was an average hitter, although later I was able to hit a few more home runs, despite the fact that I only managed to hit a little more than a hundred in the National Series.

—Your case is that of an atypical slugger, because you received more walks than strikeouts…

—At first I was hitting line drives and doubles and things like that. Then I remember that in a Youth National Championship that Roberto Ledo managed in one of the eastern provinces, he always told me that first basemen had to pull the ball and hit home runs. So I was more of a hitter from the center of the field to the opposite side, and that’s when I started to pull a little more and the results came. From that moment on I started to receive more walks. I think I was always very disciplined at home and I didn’t get too many bad balls, which is why I got a lot of walks. Rene Arocha He always told me that if he were the team manager, he would have put me in leadoff because I got on base a lot.

—In the years you played, it was not very common to see baseball players in Cuba who were very dedicated to the gym. But in your case it was obvious that you were ‘eating up’ the irons.

—I liked the gym. All the players had to do that preparation, but a few like Antonio Sarduy, Jorge Salfrán and I were more attracted to weight training than the rest. In that sense, Professor Iván Román helped us a lot at Fajardo. He guided us a lot on the correct way to strengthen our shoulders, back, and legs, in order to then face the demands of the National and Selective competitions, which came shortly after.

—Do you think that Industriales in your time should have won more championships? What was the atmosphere like in the team?

—Certainly we could have won more, but you have to take into account that at that time baseball was stronger and the teams had very good hitters and pitchers. I won twice, in 1992 with Jorge Trigoura as manager and in 1996, with Medina. As happens in all teams, there was always some disagreement, but in general we got along very well. For example, the team where I played was a spectacular group and we had the best relationship between us: Juan Padilla, Germán Mesa, Lázaro Vargas… And the same with the catchers, from Medina to Francisco Santiesteban or Armando Ferreiro.

—How did you feel when you were eliminated from the national team for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics? Do you think it was a fair decision?

—I was a bit disappointed because it was the first Olympic medal in baseball and that year I had hit very well and played very well in all the games. Of course, on that team there were excellent first basemen like Lourdes Gurriel, Kindelán and Vargas, who could be used as a utility player. I played only one position, although I had occasionally played in the outfield. I remember that they called me, I met with the head coach Miguel Valdés, they told me that I was not going to be part of that team, that I was too young and so on.

—You had traveled to the United States several times before you decided to take the step of ‘staying’, until you did so in 1996…

—That was a difficult decision and it took me a while to make. I had come to the United States before and had not stayed. Even on the occasion of a Cuba-USA match, Arocha, who is my friend, came to see me (imagine, he is from Regla and I am from Guanabacoa), and I decided to return because at that time my daughter had been born and I did not know if I would see her again. Then I returned for the 1993 Universiade, in which Rey Ordóñez and I defected. Eddy Oropesa. Rey told me about it and at first I said yes, but then I regretted it. By 1996 I was decided not to return. I couldn’t stand it any longer in Cuba and I took advantage of the opportunity to win with Medina to defect on the trip that was given to the champion. We had a bumpy ride but well, I’ve been here for 28 years, very calm with my family and sure that I made a great decision that time.

—What prevented you from reaching the MLB?

—There were several factors involved, but I think the main one was that I didn’t pick up a wooden bat in Cuba. The adaptation from aluminum to wood is difficult, some adapt more quickly, others take longer… I even played in Triple A, where I had some not very good results, but at least acceptable. To top it off, I was in the Tampa organization, which at that time began to sign players who were ‘back’ like Fred McGriff, Jose Canseco and Julio Franco. I was with Tampa for four years and then they decided to send me to Mexico, where I did much better… I played with the Tigres, with Perico, I played in the Pacific League, which is a little tougher… I think that the reason I didn’t make it is because of the sudden change from one bat to another. Because later I got used to it and had better results, but time had passed. As you know, you can’t come here when you’re old.

—Of the Cuban first basemen you saw, which were the three best?

—I played with Marquetti for three or four years before he retired and I think he and Antonio Muñoz were excellent. And everyone knows that Kindelán started as a catcher in the National Series But he played a large part of his career as a first baseman. Those three are my favorites.

—Who is your All-Star of Cuban baseball?

—I would put Juan Castro as a catcher, Muñoz at first base, Padilla at second, Germán at shortstop, Omar Linares at third, and in right field Luis Giraldo Casanovain the middle Victor Mesa and in the left Armando Capiro. The right-handed pitcher would be Rogelio Garcia and the left-handed, Santiago ‘Changa’ Mederos.

—The way baseball is played in Cuba today is light years away from that of the 1980s and 1990s. What should be done to get back on track?

—I repeat that I had a very solid time in baseball, but we cannot take away the merit of those who play today. In my time there was not so much emigration. The first one who stayed was Arocha, then two or three more followed, then William Ortega, ‘Chuly’ Ametller and I stayed, and it has always been a massive exodus. Prospects leave and managers go crazy. Imagine if you have a player in the regular lineup and suddenly they tell you ‘no, he left for the United States, for the Dominican Republic, for Mexico’…

Of course, I tell you that in the game I played there was much more love for the jersey and more desire to play to be champions. I was watching this playoff between Industriales and Santiago de Cuba And I think we need to work more on technical and tactical preparation. Those teams made 31 mistakes between them. That’s unheard of. In my time, we practically didn’t make any mistakes.

—What do you currently do?

—I am a therapist for children with autism. I work with them from Monday to Friday and in my free time I drive for Uber.

—Have you been to Cuba since you left? Do you miss it?

—Of course I miss Cuba. I went in 2004 and I haven’t been able to go back. My parents died but I still have a little bit of family there. You miss your homeland and being in the neighborhood and going there and chatting on any corner. I would like to go back one day, but I don’t have any plans to do so right now.