When someone pronounces the word “teacher”, a figure that inspires, transforms and guides is evoked. For Gladys, that word once encapsulated his entire world and identity. Graduate of a Bachelor of Spanish and Literature from the University “José Martí”, in the province of Camagüeyremember the years of sacrifice dedicated to reaching your goal of teaching.

The change was not immediate or easy. Gladys recounts how, little by little, working and economic conditions were eroding the passion he once felt to teach. “There came a point where the salary did not reach the most basic, and I had to decide between continuing in something I loved or looking for a way of holding my family,” he confesses with a stop sadness. That crossroads, so common among education professionals in his country, marked the beginning of an uncertainty and resignation stage.

“My dream was always to be a teacher, to reach children, teach them, especially those who have difficulties,” he says. However, her current reality is far from that vocation that filled her with satisfaction. Today, Gladys works as a manicurist, a trade that, although it allows him to survive, does not fill the emotional emptiness that let him leave his profession.

Being professional in Cuba once was synonymous with respect, economic stability and personal fulfillment. However, in the current context, more and more professionals face a discouraging reality: insufficient salaries, a restricted labor market and the need to look for economic alternatives that often move them away from their dreams and vocations.

Free education, limited opportunities

Cuba, a country known for its free education system and its high rate of university graduates, faces a painful paradox: the lack of decent opportunities for its professionals. The deficit of 17,278 teachers, recognized in September 2023 By the Ministry of Educationreflects a crisis in the education sector that transcends classrooms.

This situation not only affects professionals, but also has a direct impact on the quality of the education system. With fewer teachers in classrooms, schools must resort to temporary solutions, such as increasing the number of students per class or hiring uncomposed personnel to cover vacancies. In turn, this generates a vicious circle: the teachers who remain face a greater workload, which increases wear and reinforces the decision of many to leave the profession.

The salaries of most professionals range from 2,100 and 4,000 pesoswhich is equivalent to an amount between 10 and 50 dollars per month, according to the change. However, the cost of essential goods for daily life widely exceeds this figure, with a value exceeding 30,000 Cuban pesos (approximately USD 80-100). This imbalance has led many to abandon their work in the public part to devote themselves to better paid activities in other sectors, such as tourism, gastronomy or personal services.

The situation is not exclusive to the teaching, but extends to the sector of doctors, engineers, lawyers and others. The stories of Gladys and Liliana are just a microcosm of what thousands of Cuban professionals face.

Gladys confesses that his current work as a manicurist generates more income than his old work as a teacher. “It’s sad because one compares. In the beauty sector I won much more than working for the State,” he says with obvious frustration. This contrast, for Gladys, is not only a blow in economic terms, but also a painful reminder of how the current system seems to dismiss the value of those who educate future generations.

The quality of medical supplies is another aspect that has significantly impacted health services. This issue was admitted by Cuban Prime Minister, Manuel Marrero Cruzduring his speech at one of the latest sessions of the National Assembly of Popular Power last year. As a consequence, many health professionals are forced to “invent” solutions, while others choose to resign, fearful of facing complaints for possible bad practices in the face of criticism shortage of resources.

Dianelis, a girl graduated from the University of Medical Sciences of Las Tunas, shares her experience: “It was not easy to study in that institution, but I did it because since I was a child I had dreamed of being a doctor and helping people. To attend the university, I had to travel 45 kilometers, and the conditions were really bad.” At the beginning of her professional career, the harsh reality hit her: “There were no supplies to serve patients, not even means of transport. I worked in the Manatí Polyclinic, in Las Tunas, but this situation led me to leave my position. No one can imagine the impotence I feel; I wanted with all my heart to help those who needed it, but the basic conditions that should be present in any medical center simply did not exist.”

The additional difficulties of being a professional woman in Cuba

On the other hand, Claudia’s story illustrates the additional burden that many women face in Cuba. As a general doctor, he works long days in a neighborhood office, in the municipality of Placetas, Villa Clara, where the salary ranges from between 4,000 and 7,000 pesos, counting the guards. However, this barely covers a part of the basic expenses of your home. Mother of two young children, Claudia dedicates hours to domestic tasks and in the care of her family, so, she says, she cannot make many guards a month.

“Being a woman in Cuba is like having two jobs. You try to be good in your career, but you are also expected to be the one who takes the house. And all this, winning less than I need to pay the uniform of my children,” he explains.

The work and economic context in Cuba affects all professionals, but women face additional challenges due to gender inequalities. According to a recent UN reports, Cubanas dedicate an average of seven hours a day to unpaid works (Household tasks and family care), which limits their opportunities to fully develop in the workplace.

According to the aforementioned report, professional women are usually more likely to accept precarious or informal jobs, since they allow them greater flexibility to meet their family responsibilities. As a result, they face a double penalty: lower income and less professional recognition. For Claudia, the medical interviewed, this situation is particularly frustrating: “We are the most sacrificed, but the ones we receive least. And that is not fair.”

Economist Omar Everleny Pérez Villanueva has pointed out that the average salary in Cuba is insufficient to meet basic needs. According to its calculations, a Cuban would need an income greater than 32,000 CUP per month to access essential goods, while the average real salary is well below that figure. This explains why many professionals are looking for alternatives in the private sector, where they can obtain higher income.

In addition, inflation has aggravated the situation and has further reduced the purchasing power of state workers, who have been pushed into the private sector or even towards informal activities.

Migration has become an increasingly common option. According to preliminary data from 2023, more than 300,000 Cubans emigrated during the year; Many of them are professionals who left the island in search of better opportunities.

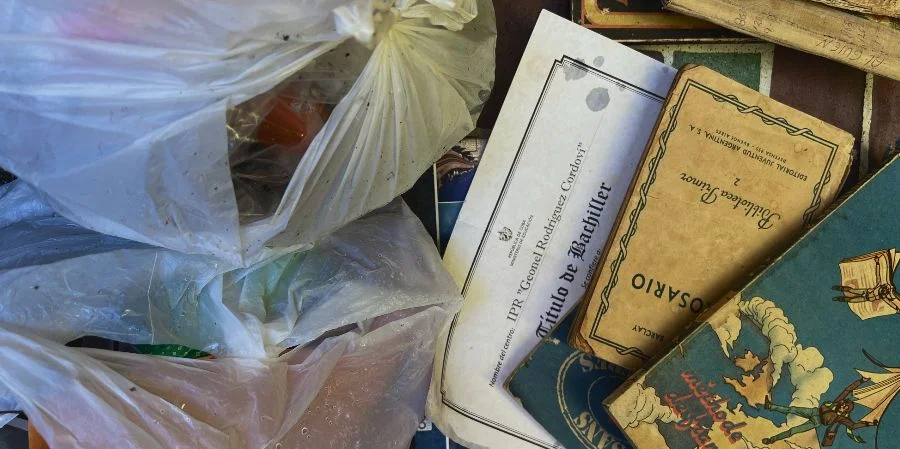

Such is the case of Liliana, who after finishing her studies, sought to develop as a professional, but soon realized that being a teacher in Cuba was a path full of limitations. The low salaries and precarious working conditions caused him to abandon his work, leaving behind what his dream had ever been. Liliana received as a teacher about 4,000 pesos per month, from there she could only buy “a chicken package, an oil knob, rice and some personal hygiene.” “I didn’t want to live subjugated by a dream that did not satisfy me,” he confesses.

Without future perspectives in his country, Liliana made the difficult decision to emigrate to Surinam. This step was not simple, especially being a woman, facing not only the economic challenges, but also the weight of machismo and the misogyny that often surrounded her. Liliana explains that she now works as a waitress, and with what she wins, she can “live well” and help her family in Cuba.

Like Liliana, Dianelis also decided to leave her country due to the lack of job opportunities and her opposition to the government. He currently resides in the United States, where he works as a manager of Wendy’s, a fast food restaurant. “Now I don’t depend on anything or anyone. I not only cover my basic needs, I help my parents too; since I arrived in this country, I live as a person and I don’t have to survive as I did in Cuba,” he says. Although he has not been able to exercise medicine in his new home, Dianelis highlights the difference in medical care: “Last year I became a mother, and I cannot explain how different everything is in hospitals here compared to those of my country. It is sad.”

The exodus of professionals, an alarming reality

In 2023, approximately 43,000 workers were disconnected from the National Cuban Health System, according to information from the National Office of Statistics and Information (ONEI). This entity considers the casualties of doctors, nurses, stomatologists, as well as auxiliary and administrative staff, among others. At the end of 2022, the total workers in the health sector was 464,118, while in 2023 that figure descended to 421,120.

The migration of Cuban doctors and teachers has become a growing phenomenon that reflects both the search for better living conditions and tensions in the social and economic systems of the island. Facing the salary limitations and lack of resources in their respective fields, professionals are driven towards countries that offer them greater labor opportunities and economic stability.

The aspiration of many Cubans is emigrating. Gladys talks about migration as an idea that constantly crosses his mind. “It would be very difficult to leave my family,” he says. But staying in Cuba has not been simple. Frustration, lack of recognition and low wages in the education sector ended up demotivating it.

“When you have a sense of belonging, you really care what you do. It’s very sad when they start trampling and belittle your work,” he says sadly. Professional devaluation not only affects his self -esteem, but also his yearnings: “I have felt sorry for leaving my dreams, because being a teacher was what filled me as a person.”

The stories told above are just a sample of a problem that affects thousands of Cubans. The decisions that professionals make, either migrate, work in the private sector or devote themselves to informal activities, have deep personal and social consequences.

The economic and labor context in Cuba has significant challenges, particularly for women, who usually assume a considerable burden within society. It is important to create spaces for dialogue in Cuban society that allow visible these problems and work in joint solutions. Among the possible strategies are the implementation of policies aimed at guaranteeing adequate wages and the promotion of gender equality in the workplace.

As Gladys says: “We want more than just: live dignity about what we know how to do. But as long as that is not possible, we just have to survive.”