Obedience is a double-edged rule of conduct, or even a value. Honoring parents is confused in authoritarian societies with submitting to their mandates. In the social field, it is taught to obey the rules and abide by the law, even when it is unfair. Before the mandate of obedience there is, however, a certain margin: free will allows us to choose based on our own principles, resistance to injustice or oppression can lead to breaking with the norms and laws even if the cost is high.

Without completely questioning the sense of obedience to social values due to personal whim or unruly tendencies, the film version of the “childish” classic, Pinocchio, by Guillermo del Toro, invites us to reflect on the primacy of obedience in authoritarian and suggests, in contrast, the value of disobedience when it arises from human feelings such as solidarity, reciprocity or love.

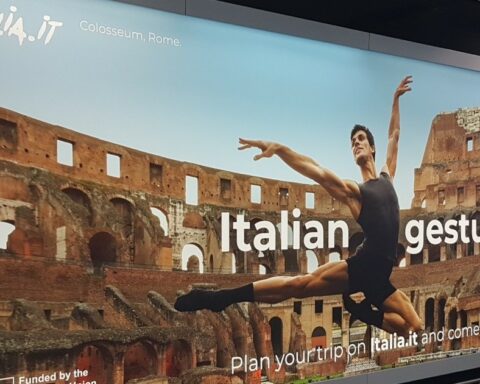

In this animation film (stop motion) of great beauty and extraordinary technical quality, del Toro proposes a story far removed from Disney’s sweetened version, which situates the story of Geppetto and Pinocchio between the First World War and the rise of fascism in the Italy in the 1930s. As in the original story and the children’s film, Pinocchio is a wooden puppet with a life of its own –here breathed in by the forest fairy to alleviate the loneliness of its creator– whose adventures culminate, however, in deeper learning than adaptation to social uses.

From his entrance into the human world, Pinocchio appears as a confused being, fascinated by novelty, who ignores everything in the world, and is carried away by curiosity and a desire for fame that seems innate in him. If, contrary to the will of the father and the orders of the authorities, the world of entertainment offers him applause and popularity, behind the scenes lies the exploitation and the desire for profit that end up breaking his innocent trust in an ambitious businessman who, at his time, flirts with political power, also prone to spectacularization to attract the masses.

Liberation from a master does not imply, in a vertical regime, freedom from other constraints. Fascism not only enacts obedience to the Duce, it also expects from its citizens the willingness to sacrifice themselves in the fight. If heroic masculinity in a war context means putting orders and the “cause” before other loyalties, here both are questioned from the less solemn level of personal relationships. If Pinocchio overcomes his misadventures, it is not only because he is capable of learning from them and becomes more human, it is also because others recognize something of themselves in him and because, unlike those in power, there are beings (children, animals) who rescue friendship, empathy and solidarity, even in the midst of destruction and war – or precisely against the lethal dynamics of violence that is setting the world on fire.

Sharp in its critique of the false promises of show business and of fascism (whose similarity is suggested in several sequences), this is not just a political film or not. If this thread invites us to reflect on the dangers of blind obedience in this 21st century, the guiding thread of this story about “imperfect parents and imperfect children” (Sebastián Grillo, writer) moves without sentimentality. If, as in Pan’s Labyrinth, the intervention of fantastic beings can modify destiny, this too depends on human decisions. Thus, Pinocchio, a free spirit, leaves behind his egocentrism and sacrifices his exceptionality in an act of love. The generosity of those who recognize and accept him as he is, gives a new twist to his story.

With Pinocchio, del Toro confirms the power and value of art and imagination in these dark times.