The scene was a bit embarrassing: that man, the “national poet”, the fascist orator who knew how to announce the “hour of the sword”, sobbed on his knees, with his hands in prayer position, before President Hipólito Yrigoyen. And hardly a sentence came out, almost like a moan, from his mouth:

I beg you for the honor of the family…

Leopoldo Lugones thus interceded for his only son, also baptized Leopoldo, whom everyone called “Polo”. That boy had made a slip: rape children interned in the Olivera Reformatory, of which he had been director during the government of Marcelo T. de Alvear. And he was about to be sentenced to ten years in prison.

At that time –at the beginning of the autumn of 1929– his status as a perverse polymorph was already the talk of high society in Buenos Aires. However one virtue had to be recognized: his love for animals. In fact, when he was just a teenager, his father caught him sodomizing a chicken. The image was difficult to digest: that skinny, ruddy creature with bloodshot eyes, twisted the bird’s neck to optimize such “performance” with its death convulsions.

The only fruit of the writer’s marital union with Juana Agudelo, Polo was born in Buenos Aires at the beginning of 1897. The father had just published his first book, the collection of poems “The mountains of gold”, inspired by French symbolism. And he was still in his socialist stage.

Now, already consecrated at the age of 54 in the universe of letters, Lugones begged the President for the acquittal of his offspring. Uncomfortable with the situation, the old radical leader reluctantly agreed.

On September 6, 1930, Yrigoyen was overthrown by General José Félix Uriburu. The coup proclamation had been drafted by Lugones. “Von Pepe” – as the new president was called due to his Germanophile sympathies – reserved a crucial mission for the young Polo.

the inquisitor

About to turn 32, Polo was short-haired, with cloudy eyes and sparse, gelled hair.

-Thank you, general. I’m not going to let him down,” she blurted out in a high-pitched voice.

Uriburu, entrenched in his desk, was scrutinizing him with approval. He had offered him the head of the Political Order Section of the Capital Police. That designation included the rank of Inspector Commissioner.

For someone with no police training and a record for sex crimes, such a charge was like touching the sky with your hands. “I’m not going to let him down,” Polo insisted., with an even higher pitch. The same one that was heard in his harangues during the acts of the Patriotic League, the far-right group to which he belonged since his adolescence.

Uriburu trusted him. And he smiled.

“We have a lot of work ahead of us,” was his phrase when he said goodbye.

He knew whereof he spoke. He had already established a state of siege and martial law. Thus began a sinister harvest. His favorite targets: yrigoyenist radicals, communist intellectuals and workers, anarchists, and students of the Argentine University Federation (FUA).Hundreds of immigrants were expelled from the country by the Residency Law. Prisons were overcrowded with political prisoners and there were even parodies of summary trials with executions. In this context, Polo Lugones was not a minor piece.

Unlike the repressive model applied at the beginning of the 20th century by the commissioner Ramón L. Falcón and also in the so-called “Tragic Week” –based on the intensive use of police troops and fascist hordes for the purpose of quelling protests with homicidal attacks against demonstrators– he was clearly –or shadows, in this case– a laboratory executioner.

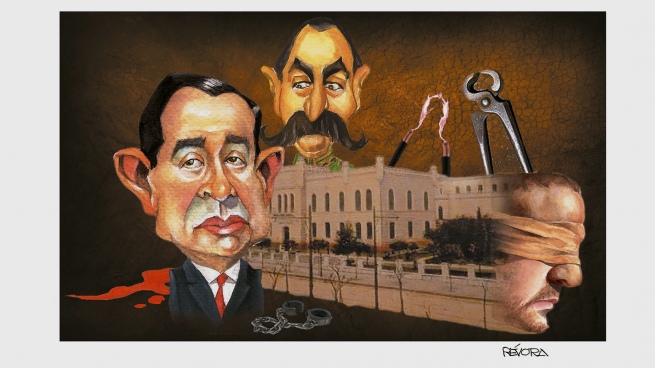

Known is his fame as the introducer of the use of the electric prod on human beings, an accessory until then only applied to herding cattle. An undeserved celebrity, since that innovation actually belongs to the Uruguayan commissioner Luis Pardeiro, who in 1926 had already put it into practice to speed up confessions.

But Polo’s merit was having imported such a methodology to Argentina. The truth is that in his own thing, in addition, he can be branded as “revisionist”, given that –after a patient historical investigation– ordered to rebuild elements of torture publicly burned by disposition of the Assembly of the Year XIII. With such tools he equipped an interrogation room in a basement of the National Penitentiary, located on Las Heras Avenue. That was his office. And there he used to alternate obtaining data under torture with field work; that is, raids, persecutions and street hunts.

On November 27, 1933, his notoriety in such matters earned him a caricature on the cover of the Crítica newspaper that showed him as a monster under an extremely eloquent title: “The torturer Lugones”.

“What is a torturer, daddy?” Little “Piri” then asked him with her eyes fixed on that drawing. Her daughter was just eight years old.

daddy’s parrot

Polo had married Carmen Aguirre in 1923, barely 15 years old. She was the daughter of pianist and composer Julián Aguirre, a pioneer of folkloric nationalism. She had two daughters with the inquisitor: “Babú” (baptized Carmen after her) and “Piri” (Susana). The marriage had its problems; the psychopathic personality of the husband and his pedophile desires they resented the relationship. So the start of the Infamous Decade caught that family in the throes of a terminal crisis. The couple separated shortly after.

However, there was something that kept Polo awake even more: his father had a mistress. Yes. The man who publicly bragged about being the “most faithful husband in the country” used to sneak a date with a student almost a teenager in a “parrot” in Retiro.

The second decade of the century was ending when she, Emilia Cadelago, approached the 54-year-old poet at the Maestro’s Library, where he usually wrote, with no other purpose than to ask him for a copy of Lunario sentimental for her thesis at the Instituto del Profesorado. The crush was immediate.

Proof of the tortuous nature of such a bond were the epistles that he used to send her. One read: “My love in your mouth, longing / My love in your soul, consolation / My love without yours, death.” It should be noted that Lugones had incurred the originality of signing the manuscript with blood and semen to underline your passion.

That detail infuriated Polo, who felt a flash of revulsion at obtaining such a letter from his police henchmen. Did old Lugones even perceive that his offspring was intercepting his correspondence?

The final blow against such romance occurred when Polo broke into the Cadelago family home to threaten his parents. And he told her that if he didn’t abandon her father, he would lock him up in an insane asylum.

Lugones spent six years unsuccessfully trying to get his beloved back.

His last public appearance was on February 18, 1937 at the wake of Horace Quiroga. The author of “Stories of love, madness and death” had committed suicide with cyanide. Lugones stood before the coffin to stroke the deceased’s forehead and say: “Horacio, you committed suicide like a servant.”

It was remarkable that Leopold Sr. committed suicide on an island in Tigre on exactly the same day the following year, ingesting nothing less than cyanide!

His son –undoubtedly the cause of this outcome– wrote much later about it: “A tremendous reality, composed of sorrow, loneliness and anguish precipitates the being and hurls him into eternity”. The phrase is part of the prologue of the “Selection of verse and prose of Leopoldo Lugones”, published by Editorial Huemul in 1971.

Lugones son committed suicide in November of that year. He was first wounded by shooting himself in the neck; then he lit a stove and suffocated to death.

His daughter Piri was murdered seven years later, in 1978, at the ESMA. Perhaps then he has seen his father’s oblique look in the eyes of his executioners.