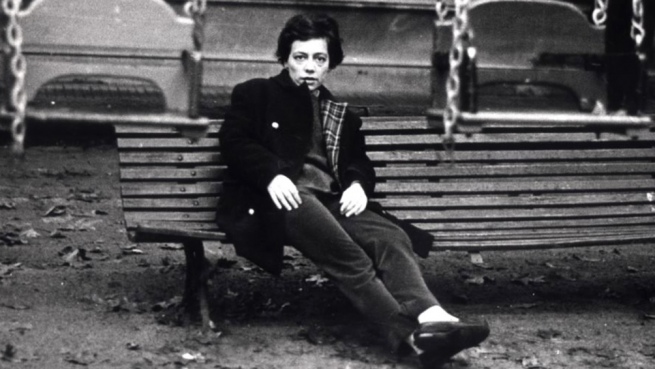

50 years after the death of Alejandra Pizarnik, iconic voice of Argentine letters, the writers Marina Mariasch and Anahí Mallol review what differences there were between the circulation of the literary character and a work that, beyond the cursing in poetry, had a vast prose and theatrical texts that retraced the tragic from a revulsive grotesque that continued to question the limits of language to name the world and things.

What distances do myth and Pizarnik’s work maintain between each other? Can it be said that the circulation of the former won over the latter? What were the essential drifts of each one? Reflect on these questions Mallol, poet, teacher and researcher born in 1968 in La Plata who, among other books, published “Postdata” and “Polaroid”; beside mariasch, poet, novelist and translator born in 1973 in Buenos Aires who counts among his titles with “Personal effects” and “We are united”.

“The character Alejandra Pizarnik, a character that the poet built with care and perseverance, and above all, based on literary models, finally, and as an effect surely not desired by her, ate up the work”, tells Télam Mallol, these days in Paris participating precisely in a meeting about Pizarnik, whose death on September 25, 1972 marks a new anniversary on Sunday.

Mallol refers “to the fact that many people know and talk about his life, his childhood, his relationship with his mother, his sexuality or his suicide, but they do not know his work well. The character, or the myth, with its ingredients of youth, defiance and a tragic figure is attractive. But perhaps what is most attractive to a certain audience is that this character allows the domestication of the indomitable, which is Pizarnik’s work”.

Happens that “its textuality is very particular and defies grammatical and logical categories, demanding a delivery that ascription to biographical elements allows to lighten, providing a fallacious impression of explanation”.

On the other hand, Mallol points out, “this type of explanation seems to be more peremptory when it comes to a woman: taming her voice by attributing madness, disappointment in love, a tragic ending: a red note that trivializes her literary power and makes her a police note, like happened with Delmira Agustini and Alfonsina Storni, among others”.

“Why don’t I find myself in a quiet little place and get married and have children and go to the movies, to a sweet shop, to the theater? Why don’t I accept this reality? Why do I suffer and torment myself with the specters of my fantasy? ?”Alexandra Pizarnik

“Marina Mariscah points to the same thing when she points out that “Pizarnik’s work was read from that episode that works a bit like a black hole that was his suicide. And unfortunately that somehow seems to absorb or color the work with a tragic, melancholic tone. A tone that is also present in the work, above all in the impossibility of linking words and things, in the fissure between language and the world”.

How much, then, did categories such as woman, daughter of immigrants, Jewish, sexuality, mental health and circumstances of death play a role in this two-way, in this mythical figure/work dichotomy, which, as in other writers and artists, constituted suicide?

Her work has other edges, Mariasch points out: “as César Aira says in the essay he wrote about her, her poetry goes beyond the character that Alejandra built for herself in her work and that she puts on stage in that name. (Alejandra , Alejandra, below I am). In this it goes far beyond the sleepwalking girl, the tramp, the little dead girl”.

Alejandra’s work -continues the author of ‘Coming attractions’- unfolds in that and in another and in others. As in that kind of poetic art that is ‘The word that heals’, to which we could add a ‘frog tail’, without any doubt, because ‘the word says what it says and also more and another thing’.

“Among the poems of ‘Tree of Diana’ and ‘Musical Hell’ -Mariash graphs- there is usually a division in reading, but for me there is a very clear continuity, that of a voice that is becoming more acute in its irony, in its sexual edge, obscene, in its cynicism and nonsense”.

Mallol says that Pizarnik’s work “is read and reread because it challenges us each time with renewed force, because it is an interrogation about the distance between language and the singularity of an experience: that impossible border prowling where something of the order of experience cannot be embodied in language and the result is a poem that precisely marks and makes a fragile bridge in the suture”.

He did it in various ways, Mallol points out, “especially from the explorations of pure poetry and from the volcanic eruption of language in grotesque prose”, which share the same impulse, “uniting art and life, where there is something that cannot be inscribed in language because it belongs to a heterogeneous order and at the same time is inscribed in this way, putting everyday language in crisis”.

In any case, and to paraphrase her answers a bit in an interview -adds the author of ‘The poem and its double’-, “it’s not about the misfortunes, but what she knew how to do with those misfortunes”.

Why do I insist on the call? Why do I analyze myself? Why do I forget my soul and don’t wring out my wet handkerchief reading ‘Bodies and Souls’? Why don’t I dress up and walk around Santa Fe arm in arm with my boyfriend?'”Alexandra Pizarnik

In an entry of “diaries” of Pizarnik, “one of the ones I like to reread the most -Mariasch rescues-, the one from November 22, 1955, wrote this paragraph: ‘Why don’t I find myself in a quiet little place and get married and have children and go to the movies? to a sweet shop, to the theater? Why don’t I accept this reality? Why do I suffer and torment myself with the specters of my fantasy? Why do I insist on the call? Why do I analyze myself? Why do I forget to my soul and don’t wring out my wet handkerchief reading ‘Bodies and souls’? Why don’t I dress up and walk around Santa Fe arm in arm with my boyfriend?'”

“Ah! -continues the text quoted by Mariasch- I know that life is very short. I know that I am not eternal. But, in reality, I do not see death. I see it far away. I say forty years but I do not see them. I see a immense space. I see thousands of days. I know that there is time. I know that I love my soul. I love myself. I love my body and I would kiss everything because it is mine. I love my face so unknown and strange. I love my surprising eyes. I love my children’s hands”.

How much did the myth of origin that each writer establishes about himself play in the construction of the public myth? “Pizarnik wanted to be a cursed poet, like Rimbaud and Lautréamont were, and she succeeded. That can also be considered a literary achievement, if we consider that her highest ideal was to fuse life and poetry, under a death drive more than of life,” says Mallol.

“That defines her aesthetics and is an indisputable element of her poetry, but the reverse premise is true – she warns -: she may have suffered, for whatever reasons (being Jewish, the daughter of first-generation immigrants, being a stutterer, being bi or homosexual). , being a girl with literary leanings in a petit-bourgeois neighborhood, being an addict or whatever), but that does not generate a work of the magnitude of hers. She was, above all, a great poet”.

To your understanding, “The best way to approach Pizarnik’s work is from the texts, not from the biographeme, or from a creative, but not instrumental use of the biographeme”.

For Mallol, what matters “is what Pizarnik does to language, the way in which he inscribes his singularity as a style” and “that style has to do with putting language in crisis: ‘How to explain with words of this world that a ship left me carrying me’ -graphics with a short text by Alejandra-, each word was thought of as a color or a stroke in a painting, they are verses so clear and precise that they are no longer forgotten once read”.

Mariasch summarizes this ‘Pizarnik quality’ as follows: “In Sur magazine he says ‘poetry is not a project but a destiny’. ‘Poetry is the place where everything happens’, he writes in a prologue to a young anthology” .