By Mehanna Hisham, University of Birmingham

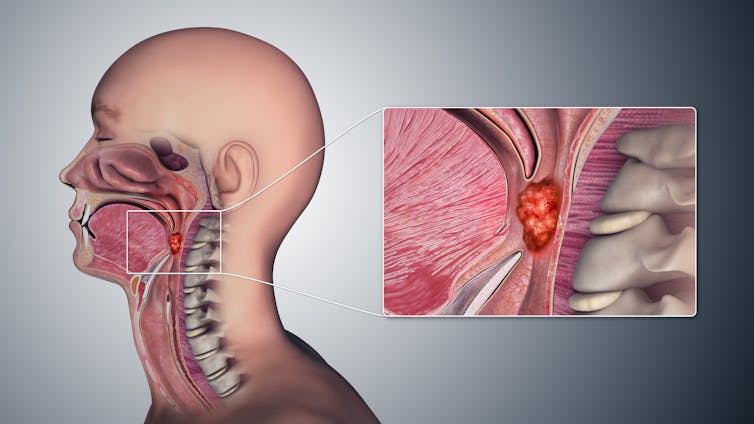

Over the last two decades there has been a rapid increase in throat cancer in the West, to the point that some have called it a epidemic. This has been due to a large increase in a specific type of throat cancer called oropharyngeal cancer, which affects the area around the tonsils and the back of the throat.

Its main cause is human papilloma virus (HPV), which is also behind many cases of cervical cancer. Currently, oropharyngeal cancer is more common than cervical cancer in the United States and the United Kingdom.

In Spain, oropharyngeal cancer is found among the ten most diagnosedwith about 8,000 new cases per year. And in Central and South America it is a growing problemto the point that an increase of 17.2% in mortality from oral cancer is expected by 2030.

HPV is transmitted sexually. In the case of oropharyngeal cancer, the main risk factor is the number of sexual partners throughout life, especially due to the practice of oral sex. People with six or more oral sex partners in their lifetime have 8.5 times more likely to develop oropharyngeal cancer than those who do not engage in oral sex.

80% of adults practice oral sex

Studies on behavioral trends show that oral sex is widespread in some countries. In a study that my colleagues and I conducted with nearly a thousand people undergoing tonsillectomy for non-cancer reasons in the UK, 80% of adults reported having performed oral sex at some point in their lives. Fortunately, however, only a small number of those people develop oropharyngeal cancer.

Although it’s still not entirely clear what it depends on, the prevailing theory is that most of us get HPV infections and are able to clear them completely. However, a small number of people are not able to get rid of the infection, perhaps due to a defect in a particular aspect of their immune system. In such patients, the virus is capable of continuous replication and, over time, integrates into random positions in the host’s DNA, some of which can cause the host’s cells to become cancerous.

HPV vaccination of young women has been introduced in many countries to prevent cervical cancer. Now there is more and more evidence, although still indirect evidencethat it may also be effective in preventing HPV infection in the mouth.

There is also evidence to suggest that children are protected by the “herd immunity” in countries where vaccine coverage in girls is high (more than 85%). It is expected that in a few decades the increase in protection will lead to a reduction in oropharyngeal cancer.

That’s all very well from a public health standpoint, but only if coverage among girls is high, above 85%, and only if one remains within the protected “herd.” However, it does not guarantee protection at the individual level – and especially in these times of international travel – if, for example, someone has sex with people from countries with low coverage. And it certainly does not offer protection in countries where vaccination coverage for girls is low, for example, USA, where only 54.3% of adolescent girls aged 13 to 15 years had received two or three doses of HPV vaccination in 2020.

Boys should also get vaccinated against HPV

This has led several countries, including the UK, Australia and the US, to expand their national HPV vaccination recommendations to include young males, following a gender-neutral vaccination policy.

But having a universal vaccination policy does not guarantee coverage. HPV vaccination is opposed by a significant proportion of some populations due to concerns about safety, necessity, or, in some less common cases, the encouragement of promiscuity.

Paradoxically, there are some tests from population studies that, possibly in an effort to abstain from penetrative sex, young adults may engage in oral sex instead, at least initially. Without being aware that this also poses a risk.![]()

![]()

Mehanna HishamProfessor, Institute of Cancer and Genomic Sciences, University of Birmingham

This article was originally published on The Conversation. read the original.