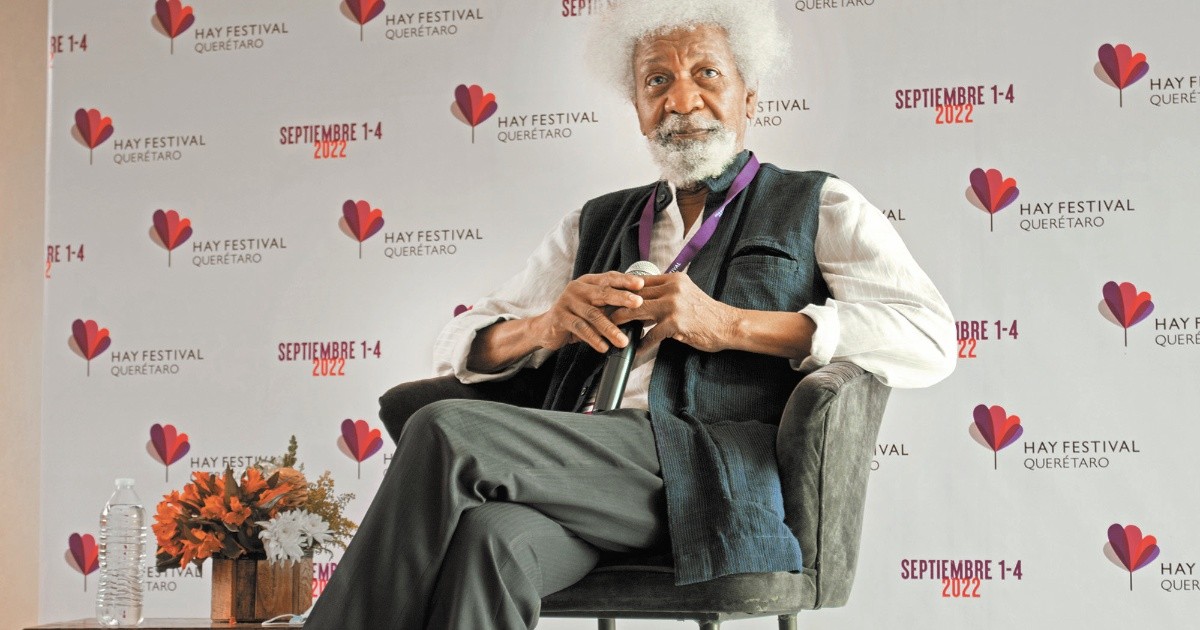

In 1986, the Yoruba playwright, poet, essayist and narrator Wole Soyinka (Akeobuta, Nigeria, 1934) became the first African author to receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. The minutes of the jury pointed out in Soyinka’s work “a broad cultural perspective with poetic nuances that shape the drama of existence.”

With works such as the novel The Interpreters (1964), the autobiography The Man Has Dead, Prison Notes (1972) or the plays The Lion and the Jewel (1959) and Death and the King’s Knight (1976), Soyinka consolidated a narrative style with which the western public could be much more interested in stories about myths, the effects of colonialism and the despicable acts of African dictatorships. Before and after the most prestigious prize for letters in the world, Soyinka has remained a critical voice of coercive forms of government.

In 1967, during the civil war in Nigeria, he was arrested for publishing a text advocating an armistice. He was charged with conspiracy and was confined to prison for more than a year and a half. In 2004, at the age of 70, he was arrested again during a protest against the fraudulent re-election of President Olusegun Obasanjo.

The two arrests he has suffered say little about the irrepressible political persecution of which he has been a victim before and after the Nobel Prize. But the laureate has not softened one iota of his critical voice.

Oppression, a matter of ego

This weekend, the author recognized for his voluminous voice and curly hair appeared in Mexico to hold a conversation with the editor Diego Rabasa within the framework of the Hay Festival 2022, where, under the pretext of his novel Chronicles from the country of the people Happiest on Earth (Alfaguara, 2021), the first fiction published by the Nobel after 50 years, spoke about the antagonisms between politics and literature.

Why are literature and fiction so threatening to power? With this provocation, the discussion was detonated at the Teatro de la Ciudad, in the capital of Queretaro.

He argued that the oppression of dictatorships, both political and religious, are nothing more than a matter of ego. “Governments are unable to assimilate more than one version of the truth and try to impose their own (…) while literature is an escape and a flag when reality becomes unsustainable.”

He added that “when we have a society with government systems that confer authority to a single individual, their society uses mechanisms such as satire to point out and criticize their rulers. I think satire is a social survival mechanism.”

various forms of colonialism

Later, in statements to the festival’s accredited press, Soyinka maintained that the term postcolonialism is a merely academic term, just as they have done with other terms such as postmodernism and post-existentialism. He stated that in historically subjugated regions not only one but several forms of colonialism persist.

One of them, for example, is indirect colonialism, one in which a country or a population group theoretically enjoys ideological and political independence, but is economically subjugated.

“And now we see a kind of internal colonialism in which the leaders are continuing with exactly the same power dynamics that the colonizing countries exercised at the time.”

a paradoxical title

The title of Soyinka’s first novel in half a century is paradoxical. The author has shared that he gave it this name after coming across a study that claimed that the Nigerian population is one of the happiest in the world. Paradoxically, his book is a political satire on a totally corrupt system and organ trafficking in Nigeria, as well as a call to mobilize against the abuse of power.