September 15, 2022, 7:48 AM

September 15, 2022, 7:48 AM

The almost 100 dead that left this week’s new clashes between Armenia and Azerbaijan have once again put the focus on the Caucasus, an important strategic region in southeastern Europe that suffers from deep political and cultural divisions.

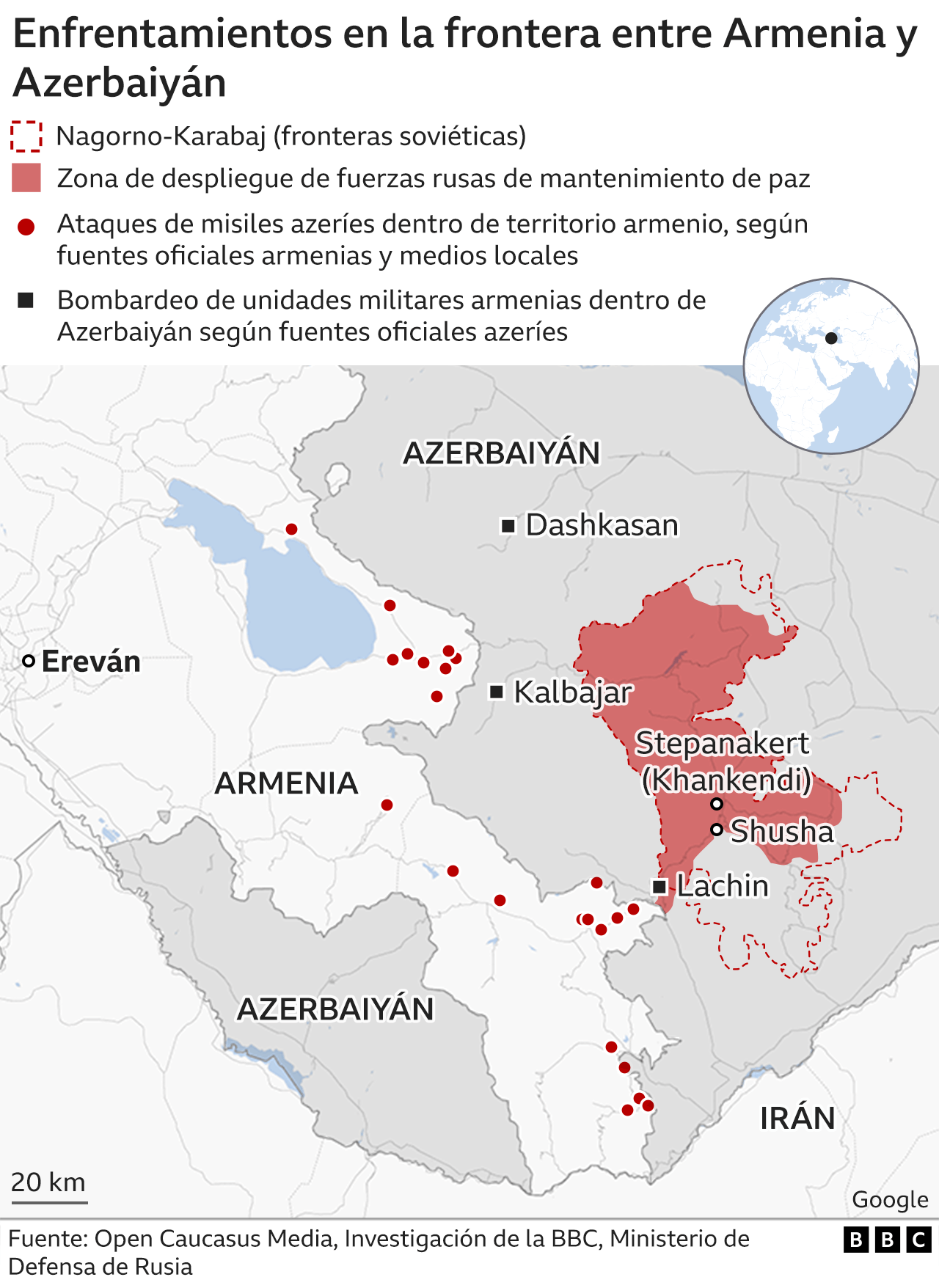

At the heart of the dispute is the conflict of Nagorno-Karabakh. This region is inhabited by a majority of ethnic Armenians, although international borders recognize it as part of Azerbaijan.

For decades, these political-territorial discrepancies that also affect religions and cultures have led to bloody wars and frequent confrontations with tens of thousands of deaths.

One of the origins of this conflict is in the particular borders created during the Soviet Union.

A complex territorial framework that critics have defined as a “kind of divide and rule” that to this day affects several states in the region.

conflicting borders

The Caucasus is an important mountainous region that for centuries has seen how different ethnic groups, religions and empires have claimed their plot of control.

The modern Armenia and Azerbaijan that we know today were integrated into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) when it was formed in 1920.

Nagorno-Karabakh, also known as Upper Karabakh, is a ethnically Armenian majority regionbut in 1923 the Soviets handed over control to Azeri authorities and it became an autonomous oblast within the then Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan.

Upper Karabakh is still populated by approximately 150,000 Armenians. For them, this region is part of Greater Armenia, an irredentist idea that brings together the territories that have historically been populated by the Armenian Christian-Orthodox ethnic group.

In other words, in the middle of a majority Muslim republic like Azerbaijan there was a territory inhabited by Orthodox Christians.

According to Paulo Botta, an expert on the Middle East at the Argentine Catholic University, this type of border drawing was a common practice in the USSR “to avoid any type of homogeneity in all its republics.

A “divide and conquer“ in every rule,” he told BBC Mundo.

This idea is endorsed by analysts such as the British historian Simon Sebag Montefiore, who in an article in New York Times he argued that “Stalin embraced the imperial mission of the Russian people and designed the USSR using his knowledge of ethnic disputes in the Caucasus to create republics within republics.”

This network of borders has influenced several ethnic-political conflicts that occurred after the disintegration of the USSR, such as the Chechen wars of the 1990s, the one in Georgia in 2008 and those in Armenia and Azerbaijan.

“Ghost States”

Nagorno-Karabakh belongs to a kind of category known as “ghost states” that BBC Mundo has recently reported.

They are entities that have expressed the desire to be independent states and that have some typical characteristics but that are not recognized as such by the international community.

The political scientist Dahlia Scheindlin, specialized in foreign policy and international relations, explained to BBC Mundo that most of these “ghost states” have emerged in places where there have been ethnonationalist conflicts, which would explain why many are in the former Cold War communist bloc.

“During the disintegration of the USSR there was a series of ethnonationalist conflicts and that is because it was a large and expanding empire, with many different ethnonational groups. And, when it was divided, one way these groups found to rebel against the leadership communist was to embrace their national identities,” says Scheindlin.

The expert also indicates that the USSR had a policy of trying to change the demographic configuration of many places by sending an ethnically Russian population to live there.

“All these attempts to engineer national identity over the years led to the rebellion against these dynamics, once the USSR fell,” he says.

How did the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan start?

In 1988, amid the tensions caused by the disintegration of the Soviet Union, Armenians stirred up a revolt in Nagorno-Karabakh so that it would be managed by Armenia.

This increased when, in 1991, the Soviet Republic of Azerbaijan abolished the autonomy of Upper Karabakh, provoking an Armenian nationalist movement that declared its independence.

Then a bloody war broke out, with about 30,000 deadhundreds of thousands of displaced people and reports from both sides of ethnic cleansing and massacres.

In 1993, the Armenians retook control of Nagorno-Karabakh and more territory around Azerbaijan. Later, in 1994, Russia mediated to negotiate a ceasefire.

Following that deal, Nagorno-Karabakh remained part of Azerbaijan, but since then it has been governed most of the time by a self-proclaimed separatist republic managed by ethnic Armenians and supported by the Armenian government.

Several peace talks have been held since then, mediated by the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, a body created in 1992 and headed by France, Russia and the United States.

However, the clashes continued and in 2016 dozens of soldiers were killed on both sides.

Between September and November 2020, new clashes lasted for six weeks until Russia again intervened to implement a ceasefire. Under the terms of the talks, Azerbaijan retained several areas it conquered during the conflict and Armenian troops withdrew from them.

On that occasion, more than 6,000 soldiers died and the consequences were interpreted as a defeat for Armenia.

Now, the clashes this Monday, which caused around 50 deaths on each side, remind us that the conflict is still alive at a time that is already difficult for the region due to the war between Russia and Ukraine.

complicated resolution

Several experts agree that current geopolitics makes it difficult to resolve conflicts such as the one between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

In part because Russia itself, to extend its influence, “has been intervening in these conflicts with a direct armed presence in some of those territories or by supporting separatists,” Scheindlin explains.

Isidro Sepúlveda, professor of contemporary history at the National Distance Education University in Spain, believes that both Armenia and Azerbaijan are under the Russian influence expansion program.

“What happens is that the Christian-Orthodox links between Russia and Armenia are stronger. Meanwhile, Azerbaijan has another Islamic-Muslim link that brings it closer to Turkey,” Sepúlveda told BBC Mundo.

Due to these links and interests, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict fully involves the powers Russia and Turkey.

Many nations look to this part of the Caucasus with the nervousness that another war could emerge in ex-Soviet territory as well as in Ukraine.

Turkey has aligned itself with Azerbaijan and told Armenia to “stop its provocations”.

France, which currently chairs the UN Security Council, has called for a discussion of the conflict.

Charles Michel, President of the European Council, says he has been in contact with the Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashiyan and with the Azeri president Ilham Aliev to prevent further escalation of the conflict.

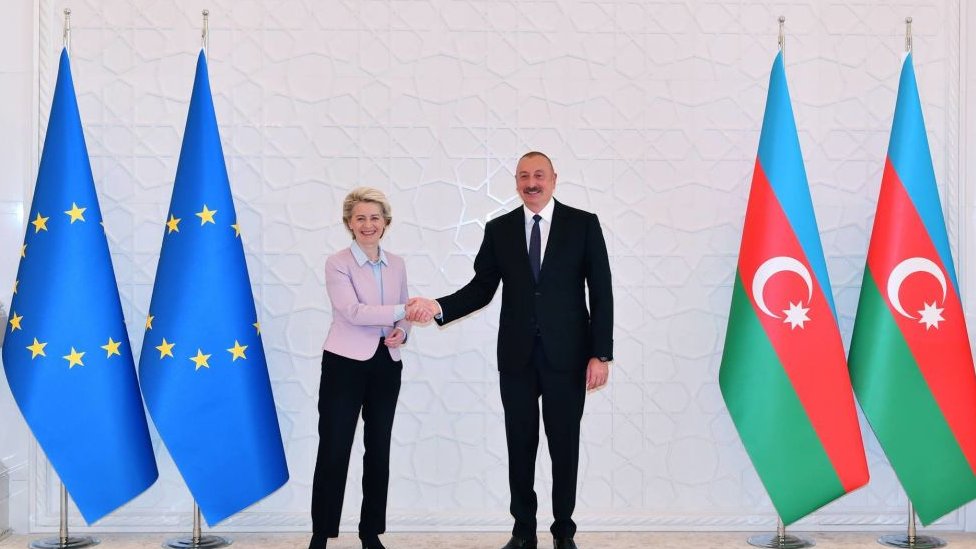

Europe wants to keep the peace in Azerbaijan, from where it imports 8 billion cubic meters of gas a year.

After suffering from the loss of gas supplies from Russia, the European Union reached a recent agreement with Azerbaijan to increase its gas supplies up to 12 billion cubic meters in 2023 and up to 20 billion cubic meters in 2027.

However, such an agreement will depend on foreign companies investing in Azerbaijan to ensure that it has such export capacity.

A conditioning factor that would surely be affected in the event of escalating another conflict in this complex post-Soviet space.

Now you can receive notifications from BBC World. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.