I won’t say that I didn’t fantasize about the idea, that I didn’t imagine myself facing it in the warm shadows of a movie theater or, perhaps, in the privacy of my apartment. Yes I did, as surely thousands and thousands have done in the last weeks and months; thousands and thousands of all ages and colors, of all tendencies and sexes. Because she is a magnet that catches even the most reticent, an inextinguishable, ardent illusion that breaks down the most fatuous barriers of morality and seduces everyone, or almost everyone, like the dream girl that she is, that she has always been and will be. regardless of their incarnations.

I went to meet him one October afternoon in Havana. I didn’t think I would be able to do it so soon, or even at all, but there she was, unexpectedly within my reach, not in some sneaky photos or rushed internet trailer, but her, really her, in all her promised splendor and imagined, no matter how much others have said or unsaid, how much those who had it first would have destroyed or glorified it, how much I knew or had seen of it myself before. A girl like that is always a kilometer zero, a highway to the unknown, to the unusual, to the surprising.

We stayed at the Yara. Of course, she had also met there with many others, with many more, mostly young, but also older and part-time, men and women, black, mestizo and white, all eager to see her, to experience the electrifying jolt of her gaze, of having her before him. Then I had no choice but to resign myself to a shared date, to prefer it at least that way rather than empty my life —Pablo Milanés said— and disciplinedly take my place in line, until a couple of hours later, and not without some other incident typical of these trances, I was able to settle into a seat at the cinema. Waiting.

Before, outside in the queue, and then, already in the room, I could see that I was not the only one anxious, excited. The expectation thickened the air and he stretched out the minutes treacherously. It provoked looking over and over again at the clocks and cell phones, it shortened our breath and conversations, it wrecked even the briefest pastime, pending as we all were for the appointed time, for the moment in which Marilyn de Armas burst in before us, before the other and before me, and everything else lost its meaning, all visible reality darkened before its dazzling appearance.

Finally, she arrived. She kept waiting a bit, but not too long, like any glamorous and cunning girl who controls the times of her appointments, her tickets. By then the room had turned off and turned on again, to turn off shortly after, perhaps due to an oversight or a choreographed suspense device, and the screen had also frozen for an instant, without references, without sound, causing the discomfort Of all of us, we were still waiting for her. Because at that moment Marilyn de Armas was not yet Marilyn de Armas, but a little and suffering girl, the little and suffering Norma Jeane, who was being led into the flames by her disturbed mother.

Soon, however, it became clear that Marilyn de Armas had deceived us and the rest, that she had cajoled us into the movies with her really not-so-blonde hair and seductive promise, and that, even if she appeared every once in a while, and sing and dance and act, and dazzle in big ads and magazine covers, and blow kisses and fiery glances at legions of journalists and fans, our date, really, was mostly with Norma Jeane de Armas, not the little and suffering girl who her disturbed mother also almost drowned in a bathtub, but the traumatized and unhappy girl who lived in a whirlwind of torments and humiliations.

Perhaps another, others, would have left the cinema in the face of deception, would have turned around furious, disheartened, and left the traumatized and unhappy girl with whom we had ended up staying alone with her traumas and unhappiness. But, on the other hand, nobody, or almost nobody, got up from their seats; no one, or almost no one, chose to leave the crowded Yara room, as one would abandon a cruise ship sinking in the icy and gloomy seas of exacerbated suffering. All of us, or almost all of us, stayed, we overcame; we accompany our girl through her tortuous and fictional existence, through her gloating fall to hell, through her endless, recurring personal debacle, through her distorted dreams and her suffering and stormy vigils.

At this point we lived the appointment personally and at the same time collectively, ruminating on her pain in unison, coinciding in interjections and pouts, in snorts and startles, united as we were by the common attachment to our girl, to our Norma Jeane de Armas and her calamitous and tremendous spiral, despite her narrative hangovers and underlined metaphors, which, after all, were not her fault, she was the victim of her life and the narrative of her life, which squeezed our hearts and eyes, and the she completely emptied, and with her us, of all eroticism, of all lust even in her nudity.

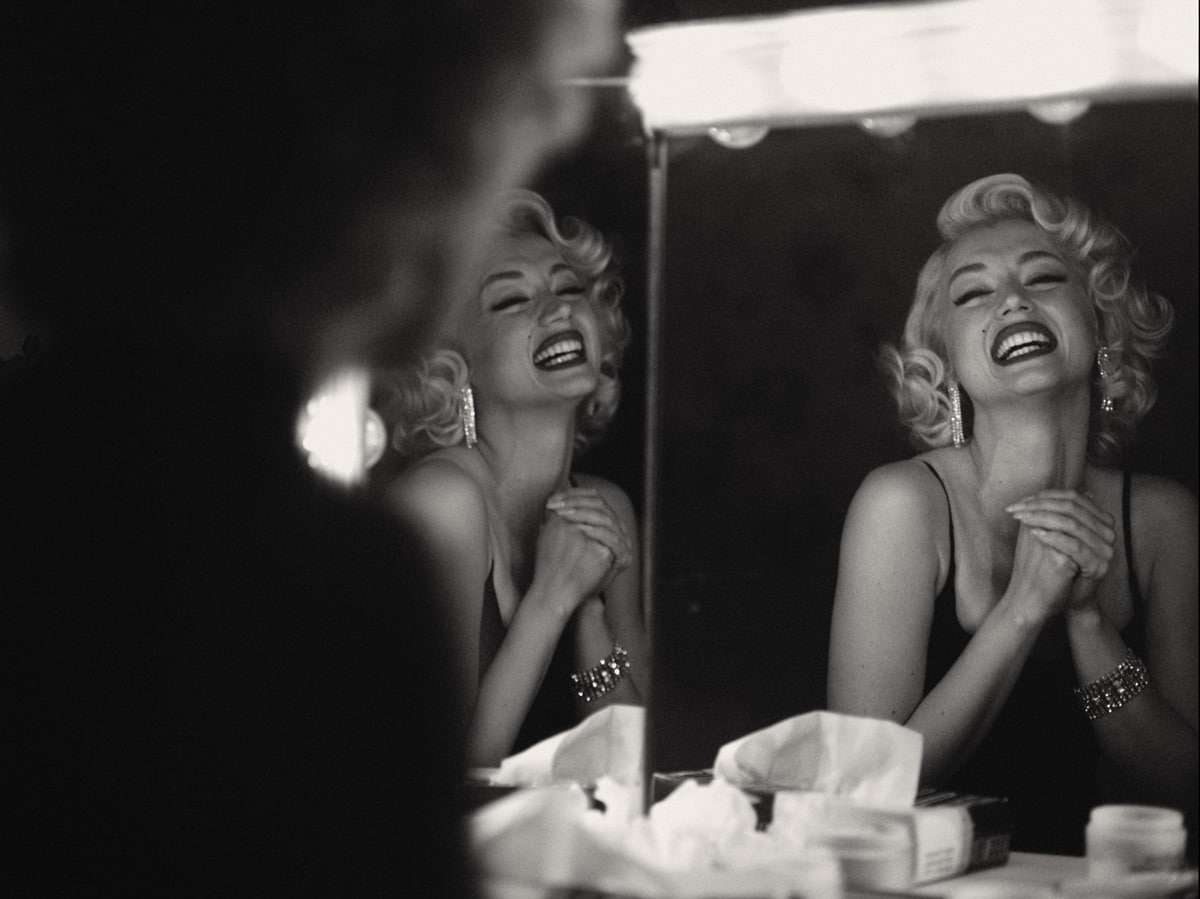

And the room went from silence to horror, from the startled or empathetic rumor to the muffled exclamation and the surprised smile, because in this, as in any good date, there were also their laughs. And also, yes, candor and naivety, and blush turned into desire, into debauchery, because our girl, our Norma Jeane de Armas, was not only agony and vexation, trauma and unhappiness, she was also, she could also be, beauty and passion, infatuation and pleasure, although these were not the healthiest, the most orthodox, nor did the mirror always return the smiling image of happiness. No, her reflections were also distorted, like her dreams, and the tricks and misfortunes then re-emerged, between brilliant and scandalous irruptions of the other, of Marilyn de Armas.

Then, when that one reappeared, I gave myself over, we gave ourselves over, to the enjoyment of our first, idyllic date, of the fascinating, captivating vision of the curvaceous platinum blonde, of the sexual bomb that blew up serenity and took over with his mere presence —with his mole, and his opulences, and his red and captivating lips— from any place, attracting all eyes around him, unleashing palpitations and salivations of lasciviousness. Because, who hasn’t ever dreamed of a girl like that, capable of paralyzing the universe with a kiss in the air, with a sensual blink, with the happy and lustful flight of her skirt over a subway grate?

In those moments, in which Norma Jeane de Armas was Marilyn de Armas, the sparkling and provocative girl, and not the girl dazed by her traumas and her barbiturates, the date, my date, our date, changed rhythm and color, and I looked at her, we looked at her, stunned by her exuberance and apparent joy, by her infinite power of seduction, and we were sorry we couldn’t offer her one of those diamonds that she loudly proclaimed as a girl’s best friend, and we were moved by her appearances before the mirror, with their radiant swaggers on the screen, and we envied the luck of Bobby DiMaggio and Adrien Miller for having had her so close, for having touched her, the dazzling and fictional Marilyn de Armas, not only the other, the suffering, and the stories, and sorrows, and tragedies, and unhappiness of the latter, of our Norma Jeane de Armas, remained just like a distant, phantasmagorical echo, in the face of so much overflow.

But, you know, happiness is short-lived, and even less so if you are Norma Jeane de Armas, or like me, like us, one of her unfortunate occasional dates, so Marilyn appeared and disappeared fleetingly, from the set, from the screen, mirror, and plunged us into greater and greater abandonment, and left us alone with our girl, with our traumatized and unhappy Norma Jeane, not the little and long-suffering girl whom, with her disturbed mother already hospitalized, her parents cruelly abandoned by neighbors in an orphanage, but rather the girl who suffers and tears herself apart, and freudishly shrinks in the face of the irreplaceable absence of her father, and naively drags herself into the deception of which she always ends up being a victim, even of her most passionate lovers, and cries and she sinks into the fierce emptiness of her impossible son, of the violence of her losses, and wanders like a sleepwalker through an airplane and through life, and is subjugated by everyone against her will, even by the very president of the United States, perhaps even by ourselves .

Thus comes the dramatic and prolonged closing of our date, of the extremely free and painful narration of the existence of Marilyn-Norma Jeane de Armas for almost three hours that our date was, with her inert body —Norma Jeane’s— on the bed, and her specter—Marilyn’s—sensually hugging the pillow, and the sad look of her pup, whom we only get to meet at the end, and the sight of our girl’s outstretched legs receding from us, lighting up, and then they darken as confirmation of the inexorable and tragic end, in a fade to black that leaves us without the goodbye kiss, without being able to exchange phrases or telephone numbers, without the possibility of at least giving her some flowers or the glimpse of an upcoming encounter, of a next opportunity to see her, to appreciate her in her exuberant and fatal “blondness”, because we already know, we already knew, that in reality she does not die, never will, and that the end of our date will never be hers, no matter how convincing whatever it seems and for me more helpless than she has finally left us in the movie theater.