This January 8 marked twenty years since the death of my brother Rapi. His full name was Constante Alejandro de Diego García Marruz and he was born on January 6, 1949. He was 56 years old when he died.

I do not intend to remember it with sadness, because he would not have liked it. His letters, already sick with lymphoma, were always very optimistic and happy. “Enjoy the fruit,” he told me; “Worse times will come.”

He was bright, like my mother. He was always very rebellious and irreverent. He had a fine sense of humor.

He started five university courses and finished none. He said that in the first, Architecture, they called him to a meeting with the UJC (Union of Young Communists) and accused him of “having a bourgeois smile.” That would already be in the seventies. My brother could not stand the schematisms, extremisms and rigidity that characterized that organization, and must have often mocked its repeated slogans and lack of spontaneity.

He began working as an editing assistant at Icaic (Cuban Institute of Cinematographic Art and Industry) and ended up being a director of documentaries and feature films, but his true passion was drawing. Since he was a child he already drew on little pieces of paper, notebooks, napkins, whatever he found. I remember that we played with clay or plasticine and, while lychee and I made balls and very simple things, he formed figures, faces, animals.

Now that I talk about the stone, something so humble and, at the same time, so useful for developing skills in childhood, I remember with immense sadness a little girl playing in a park near my house with… a stone. He threw the stone, which must have been a ball in his imagination, picked it up and threw again. They will say that it is the enemy’s fault, but I remember that since 1960 the restriction on the sale of toys began. I return to my brother.

Rapi studied for a year at the National School of Art, but left. His training as a cartoonist was completely self-taught. I studied the books from my father’s library, with the illustrations of the great English and French cartoonists. He also studied the great painters: the details, the light. And he made sketches, studies of hands, faces. I found many of those sketches in his scripts, on little pieces of paper. They are, truly, impressive.

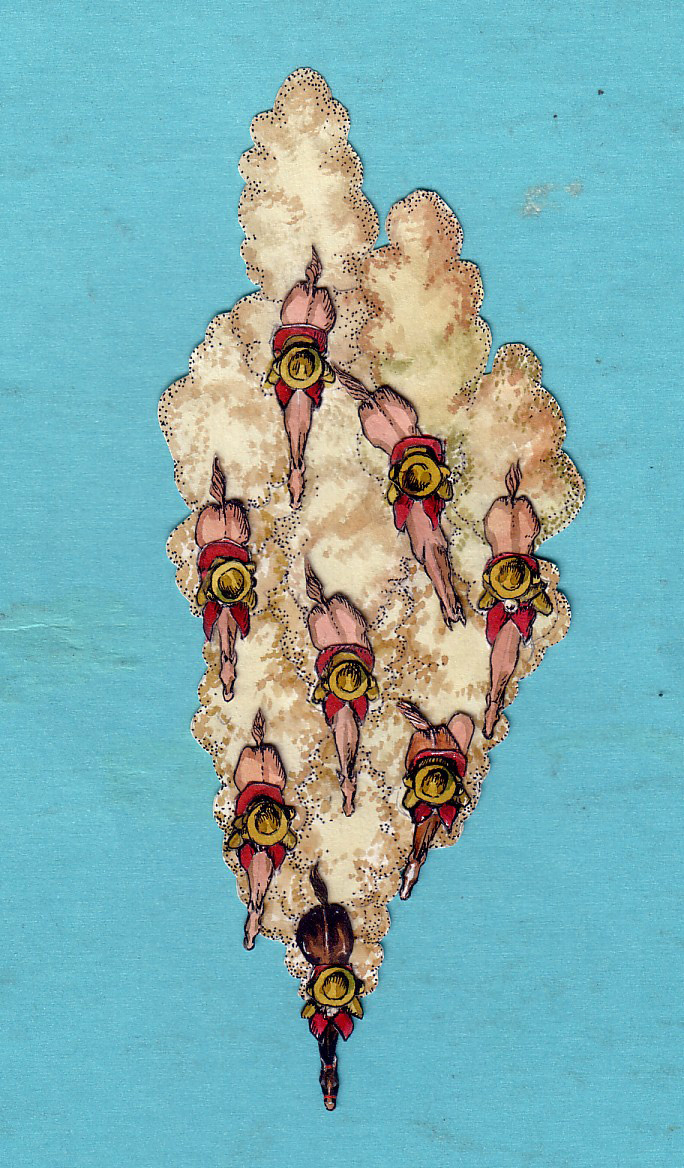

Your favorite movie, Mascaró, the American hunterbased on the novel of the same name by Haroldo Conti, is the story of a traveling circus, all dilapidated, that goes from town to town giving hope and joy. By leaving, the residents have changed: art has changed them. The film—Special Prize at the Trieste International Film Festival, Italy, and “India Catalina” Award for Best Film at the XXXIII Cartagena Film Festival, Colombia, 1993—has drawings by Rapi, miniatures that help tell the story. Rapi made the animation mechanisms for those drawings, which are, in my humble opinion, a gem.

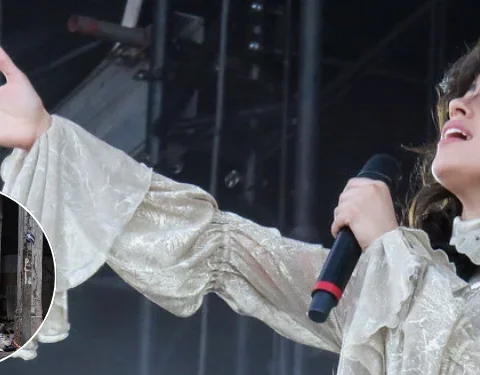

The first book he illustrated was A paper boat sails through the sea of the Antillesnotebook of poems by Nicolás Guillén. He also illustrated our father’s collection of poems for children, Eliseo Diegoand wrote the introduction. He drew posters for Icaic and album covers, including Unicornof Silvio Rodriguez.

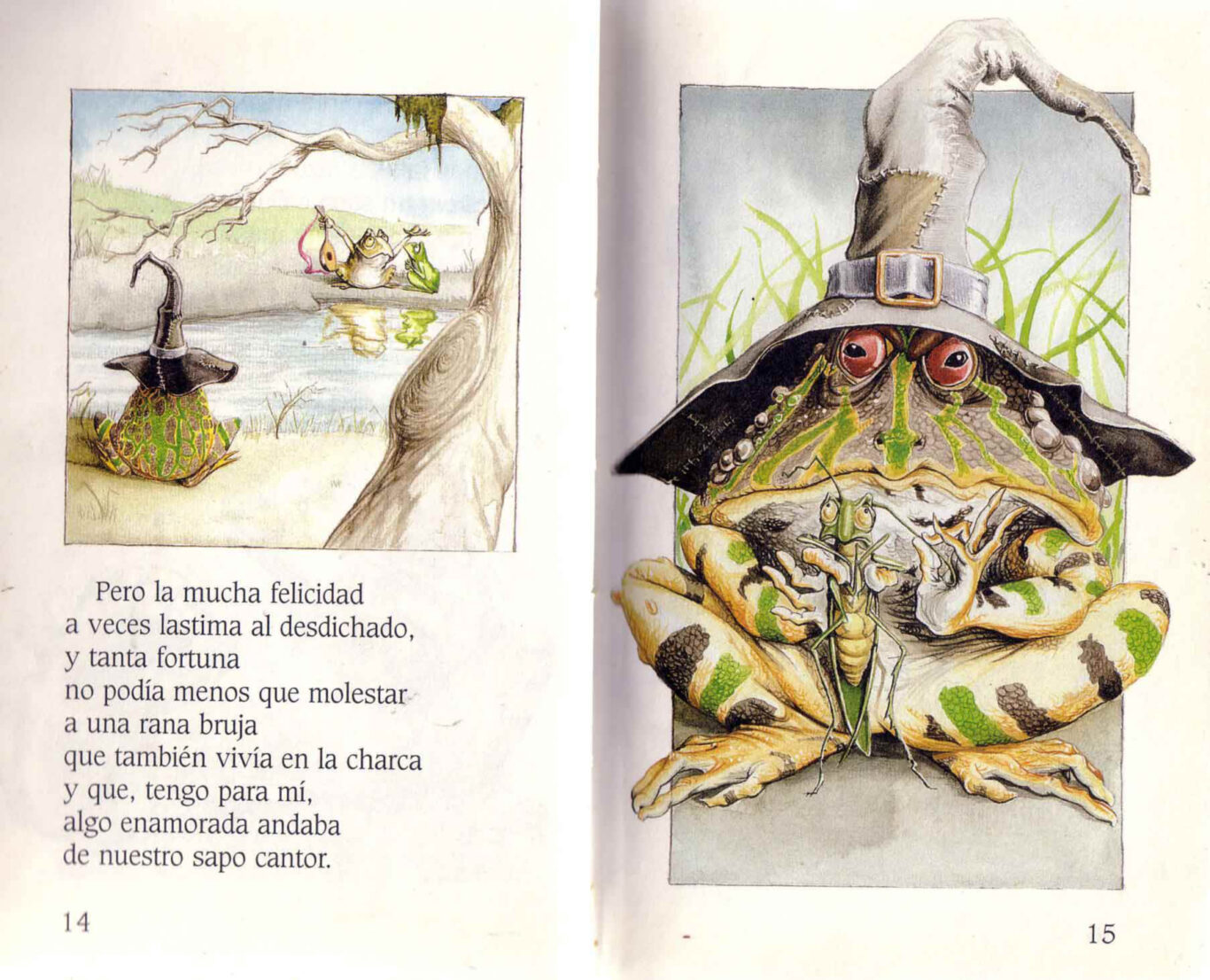

In approximately 1995, he settled in Mexico, and there he continued illustrating children’s books and collaborating in various Mexican magazines. Finally, he decided to write and illustrate his own book, The bewitched toada delightful story about a toad who sings to his girlfriend, a cute little frog, in a pond. But a witch frog, envious of his happiness, casts a spell on him and turns him into a prince!

The other book he wrote and illustrated was Didi and Professor Jinksabout the search for a goblin of whom only rumors are known and who lives in the mountains of Nepal. He wrote with great grace, imagination and confident, delicate prose.

I have scanned around 400 of his drawings, which I found in his notes, letters, scripts and scraps of paper. I scanned them and, although he no longer remembered them, luckily they remain there: in those files, in the books he illustrated, as a testimony to his talent and the great artist he was.