Holguin, Cuba. -“Before, a pound of rice cost 150 pesos and one of bean 200. After the government set prices, the pound of rice rose to 230 and bean to 320-360,” says the Holguin Abelardo Gómez Álvarez.

The price stop has produced a result other than the desired one: greater shortage in state premises and even higher prices in the informal market.

Specialists believe that this measure, improvised and wrong in a circumstance of low national production, dismiss the legal sale and worsens the food crisis. It also evidences the structural problems of the agricultural sector and the inability of the government to guarantee the offer.

The ranked prices for the retail rice and beans of national production in state markets They entered into force on March 7. The government set the price of rice free in 155 pesos in the retail network, while bean pound goes from 196 to 285 pesos.

Little more than a month after the entry into force of the price stop, the street situation contradicts the governmental objectives: the shortage of both products has worsened and prices in the informal market, the only source for many, have shot themselves.

For the Holguinero Wilfredo Benítez Soto, the measure violates basic economic laws in a context of chronic productive deficit. “When there is scarcity, prices cannot be lifted because there will be an adverse reaction. Of good intentions, the path to hell is cobbled. Here what is there is to produce, but the government has not overcome that challenge and that is why it goes by the easiest way that is the top of prices. With that it wants to appear that it is not with a cross -speaking and that something is being done,” says Soto.

The practice of running prices is cyclical in Cuba. Lucrecia Doimeadiós Lorenzo mentions past experiences that, he says, had to serve as a lesson to the authorities.

“On one occasion,” says Lucrecia, “when the prices of the meat, the pasta, the oil … everything got up. I remember that the oil and chicken had lower prices [en el mercado informal] that those who ran into. After the measure, they began to rise. ”

Experts corroborate the inadmissibility of the policy of price regulation. “Although they are made with a good intention, looking for greater purchasing power, seeking greater access of low -income people to the products, it is probably the regulation policies that the State has the most contraindications or that more problems can bring in practice,” said Carlos Enrique González García, a researcher at the Center for Studies of the Cuban economy, during an intervention in the program Blocking the box, of the Havana Canal.

The expert stressed that “the first thing that happens is that there is a dismissal of production and supply: if I run the price of a product, that product I will not produce, that product I am not going to sell, I am going to move for another product,” he concluded.

Who benefits from price regulation?

Although the announced objective of the measure is to allow the acquisition of the population to these products, the reality of perennial scarcity favors a favorable scenario for the informal market.

The poor offer of the State, explains the holguin Nelson Mesa Castro, is quickly monopolized by resellers who later sell the products at higher prices taking advantage of the crack between an unsatisfied demand and an insufficient supply. “With the top, prices fall in the state market. But as there is shortage, resellers take advantage and, in combination with state sellers, buy all rice and beans and then resell them at a higher price.”

Topped prices disrupt any profit margin, which discourages the commercialization of products that private entrepreneurs bring from the field. “Private merchants make their own management, they bring a little rice and other products in the field to sell them in the city. But with the ranked prices you cannot do business because it gives lost. Entrepreneurs cannot be put a shirt of force to lower prices, because in the end the injured party is the people,” says the holguin Eugenio Santana Muñoz.

The dependence of the imports of products that were previously produced on the island is already fed up.

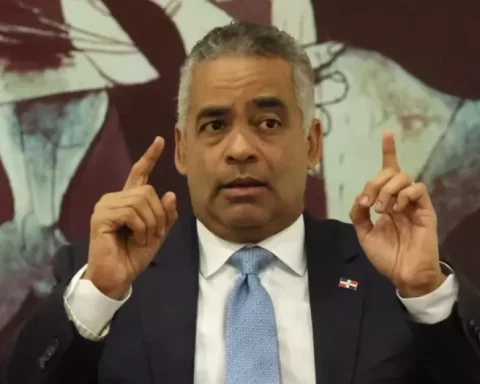

“[En] A country that produced rice, today we are importing all the rice of the basic basket. We also produced beans, and one hundred percent of the beans are importing, and the country without money. And where is national production? ” said The political bureau member Esteban Lazo Hernández during the first ordinary session of the Cuban Parliament.

The crisis enters a broader panorama of government failures in matters of agricultural and food policy. Initiatives such as the Food and Nutrition Safety Law and the 63 measures to boost agricultural production, informed with great expectations, have not been effective in eliminating the deep crisis in the sector.

Vice Prime Minister Jorge Luis Tapia admitted in July 2023 That both the food sovereignty law and the 63 measures mentioned “have not yet achieved the desired impact.”

The official blamed this failure to obstacles such as the lack of knowledge about modern law and techniques, as well as deficiencies in the integration of different actors, from scientists to productive.

Almost two years after official admissions, the opinion of the Holguineros is that the situation, far from improving, has worsened. “In Cuba rice occurred and little by little it has stopped producing because the strategies and decision making of those who direct this country have failed,” says Yoel Iglesias Vidal.

Given the threat of inspections and economic unfeasibility that create regulated prices, sellers go to various tricks to dodge regulation. This is denounced by Marcos Santana Guerrero: “The vendors put the poster announcing a topical price and tell the customer that this price is for the inspectors and that the real price is another more expensive.”