It’s not much that a black woman gets to do without receiving some kind of social punishment. During slavery, the forms of torture were clearly defined, even described in detail in certain legal documents. The torture was physical, inflicted on the flesh; Well, nothing else was an enslaved person: meat-merchandise, as useful as it was disposable once its function as a procurer of capital and other people’s well-being had been fulfilled.

In the present, the punishment against the black woman who allows herself to do and say what her desire dictates, continues to be torture; even if it is not bodily applied. The punishments are expanded through a wide range of strategies that include reproaches and public attacks, the most varied attempts to silence, mockery, isolation, degradation and insults.

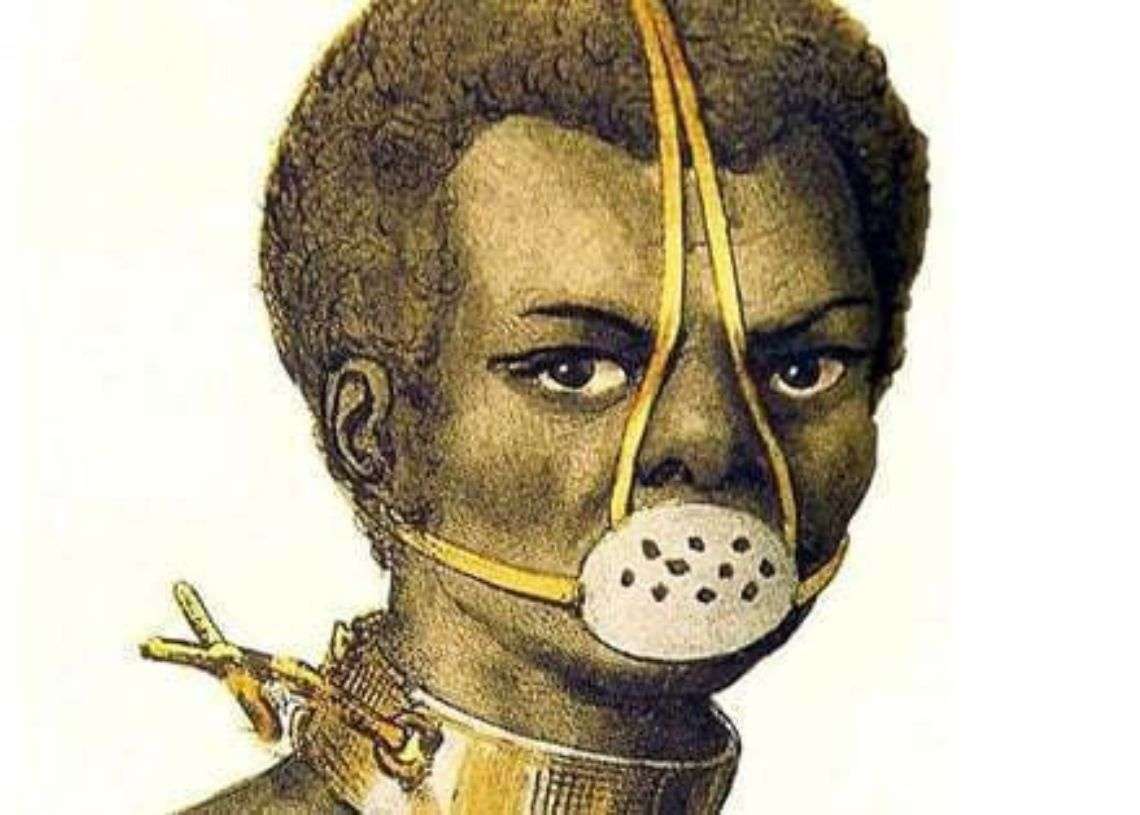

They are punishments seemingly meant to break us inside; but as harmful as the lashes, the stocks and the face down imposed on our ancestors. That is why Grada Kilomba opens his book Memories of the plantation. Episodes of everyday racism returning to the image of Anastácia’s gagged face: enslaved, martyr, queen or princess, or perhaps none of that, African or not, mestizo or not.

We know nothing of the person behind the image, popularly—never papally—sanctified and today venerated in Brazil. Uncertain is the story of the alleged Anastácia, like all the stories of enslaved Africans and their descendants in the Americas.

We do not know her origins, the acts of hers or others that led her to be punished with the mask and the metal necklace that caused her a death that we do not know how it happened either. Uncertain is even her face, since it is not certain who or under what circumstances the drawing of her was made, generally identified as the portrait of Anastácia. In fact, the original work was presented as the portrait of an enslaved man, made by French artist and writer Jacques Étienne Victor Arago in 1817-18. But later reproductions vary in one way or another the features of the gagged figure, arming and supporting the legends around the drama of Anastácia.

In the most popular images, her eyes appear blue. Some believe that it was the result of the rape of her mother, who is sometimes attributed an unverifiable Bantu origin. Others claim that she was a Nigerian princess. Her beauty, it is also said, provoked the desire and continuous sexual harassment of her masters. They say that Anastácia resisted the harassment, endured the martyrdom of the muzzle that she was forced to wear and accepted a slow death.

From one legend to another, we only have one certainty: the absence of information that allows us to reconstruct its history. We will never have proof of what really happened to her. Anastácia was unable to express herself: her mouth remained covered with the muzzle.

It is precisely what Grada Kilomba wants us to remember when confronting us with the racism currently suffered by black women, in Europe, in the Americas. Her intention is for us to understand how society still seeks to silence us. The gag is now not made of iron, but with equal violence they try to place it on us. And social media is an effective tool in the hands of those who would rather we not talk; that, like Anastácia, we cannot tell our story, say who we are, from ourselves, with our own voice.

Grada Kilomba identifies “the mouth” as the “organ of oppression par excellence”; because, as a symbol of enunciation and discourse, it constitutes the one that racists “want —and need— to control”.

A black woman should not, above all, openly express who she is and who she wants to be; she’s not supposed to explain how she sees herself. That is to say, a black woman should not define herself, because this implies an opposition to the identities that society foistes on us; It implies that we do not consider them adequate. More importantly, we reveal that they are alien constructions and that, as artificial concepts, they do not have to be true; that no supposed truth about who each of us is can come from anyone but oneself.

For this reason, when a black woman speaks from her will, and not from the desire and gaze of others, she becomes monstrous. He is a monster because nothing that comes from his crudest desire is included within the social imaginary, which is an imaginary built by European men and for centuries strengthened and supported by those who —regardless of their ethnicity, gender and sex— adopt and reproduce a Eurocentric and patriarchal worldview.

Within this way of understanding reality, the will and vision expressed by a black woman are not legitimate, rational or valid. Only if they are useful for maintaining projects not generated by us, can our arguments ultimately be heard. Social utility determines whether or not punishment is applied to us: that we are allowed to express our opinion or, on the contrary, that silence, mockery, denial and reproach are exerted on us.

These attacks are as powerful as those corporal punishments of yesteryear. They leave us just as damaged, especially when we have been receiving those blows all our lives. Because, as I said before, there is hardly any activity of the black woman that is welcomed. Perhaps, be servants, prostitutes, singers and guaracheras or athletes. That is, when we serve others: cleaning, caring, entertaining; dedicated to productive activities whose benefit does not reach us, rather, on the contrary, that the benefit serves to sustain the socioeconomic and ideological machinery that has kept us silenced and neglected from the 16th century to the present, anywhere in the West.

The blows rain. They do not fall from the sky, but from men and women reluctant to consider that our desire and our voice are valid. Meanwhile, life slips away from us dodging those blows; and to achieve this —as Grada Kilomba continues to write while quoting bell hooks— since slavery “we have become experts in ‘the psychoanalytic reading of the white Other’ and in how white supremacy is structured and executed”.

It is a constant activity, which requires large amounts of energy and, over the years, our expertise exhausts us—literally, since it has been proven how disproportionate the risk of high blood pressure is for people of African descent. But you have to survive. Just like our grandmothers and mothers did. We will survive. For our children. We are maroons in everyday life. It must not be forgotten that the maroon escapes the blow, but she also delivers it. The runaway is her and not who others want her to be. she protests. She stands in her territory. She has managed to get rid of the chains and escaped into the bush to live in it at her pace, define who is hers and call herself by her name.

My ancestors were not allowed to use, while in captivity, any other name, surname or epithet other than the ones they received from the owners of their bodies, the slave masters. If he tried, there were the muzzle and the chain around his neck. So I cannot, out of respect for my ancestors, be more than a runaway and honor the right they have conquered to present myself to the world according to who I define that I am, calling myself by the name I choose for myself and demanding that my body be touched. only from my decision.

Consequently, nothing will be able to convince me to accept the names that others want to use to define me. My profession is the one I have worked for, overcoming obstacles that have always been much higher and much higher than those faced by my white, male colleagues. Nobody has done it for me. Nobody works for me. No one can thus decide for me what my profession is. Neither can anyone, without my rebelling, touch any part of my body without invitation. No, my hair is not touched unless I place it in your hands. I am not “your black”, because that is not my name.

I remember that someone in public used to call me that, “my black” and stopped talking to me the day I also called him “my white” in public. And another that felt offended when I moved my head away from her hand that was about to touch my hair. More recently, I tried to explain to a colleague why we blacks don’t like it when white people come to curiously examine our hair, as if we were beasts on display at the zoo, a museum, the market where our ancestors were sold. But I only got her angry protest from her and, subsequently, the traditional self-victimization of the offended: “Why can’t I touch her hair? I don’t get it,” she said.

Behind her words, I heard other questions, which she herself did not know that she was silently proffering: “Why doesn’t that black woman give in to my desire? Why doesn’t she allow me to assert my authority as a white woman over her body? Why does that black woman think she owns her body?

But my arguments lost weight before her hurt little princess voice; which, of course, drew pity from the white men around us. To her, the consolation of the heroic knight, so romantic. To me, the punishment of the same character, transformed into a subjugating warrior: How dared he antagonize the white woman, take her out of her placidity and expose the limits of her idea of gender sisterhood?

Episodes like this often occur, in which the demand for respect for her body and her identity by a black woman is perceived as an act of inconceivable rebellion. Resisting the invasion of our bodies, denouncing the violence that this implies, is seen as our monstrosity; and the crowd is always in solidarity against the monster that comes to question the absolutism of the only possible truth, that of our Euro-patriarchal society.

But, that is ultimately a problem of that crowd. Their taunts and arrogance do not blur or detract from us. On the contrary, with our mothers and grandmothers, with our sisters, with all the maroons rebencúas —even though it may not seem like it, we are legion— we continue to cultivate that unthinkable, demonic terrain as Sylvia Wynter called it, from which new ways of understanding ourselves, our experience and the reality in which we live emerge.

The more those who don’t accept that I can choose myself hit, the more I do. monstrous. Yes, yes, and yes! It’s not an insult. It is very healthy to be monstrous in the face of an order that has only worked to deny my right to be, infinitely, according to my own law as a black woman.