I confess something that I am not proud of, but that I do not believe to be exceptional either: for years I repeated phrases by José Martí with the confidence of someone who thinks they know, even though I had never read the texts from which they came. I was—like so many—a serial dater.

“Being cultured is the only way to be free” was one of those sentences that he said with ease: at school events, in solemn conversations, in discussions about the destiny of the country. I even went so far as to appropriate it as if it were a personal conviction. The truth is that I never stopped to ask where exactly it came from, much less to read the essay from which it was taken.

In September of last year, during his concert on the steps of the University of Havana, Silvio Rodriguez He did something unusual: he did not repeat the phrase as a slogan, but instead read a longer fragment of the essay “Itinerant teachers. He returned it to its context. And there something revealing happened: behind a phrase tamed by use, an uncomfortable, complex, deeply political thought appeared. Martí wrote: “(…) But, in the common sense of human nature, one needs to be prosperous to be good.”

That line—systematically omitted—changes everything. Because Martí is not proclaiming a cultural slogan or handing out moral certificates. He is talking about responsibility, material conditions, concrete ethics. Being cultured, in its conception, is not accumulating titles or displaying readings; It is learning to think on your own, distrust dogmas and exercise freedom with judgment. It is a political act, yes, but in the most demanding sense of the term: emancipating oneself from ignorance and not allowing others to think for us.

In my opinion, the problem is not to become Martí scholars or to master his complete work to the letter in order to cite or refute it with philological precision. Even not knowing—when it is honest—can be a starting point: ignorance also pushes us to search, to read, to ask.

The truly grotesque thing about these uses of Martí is not the lack of knowledge, but the manipulation. It is not about ignoring Martí, but about using him badly; to twist his word so that it says what is convenient, to empty it of conflict and return it as closed certainty. That’s where thinking is perverted: when the quote stops being an invitation to think and becomes a shortcut to avoid discussion.

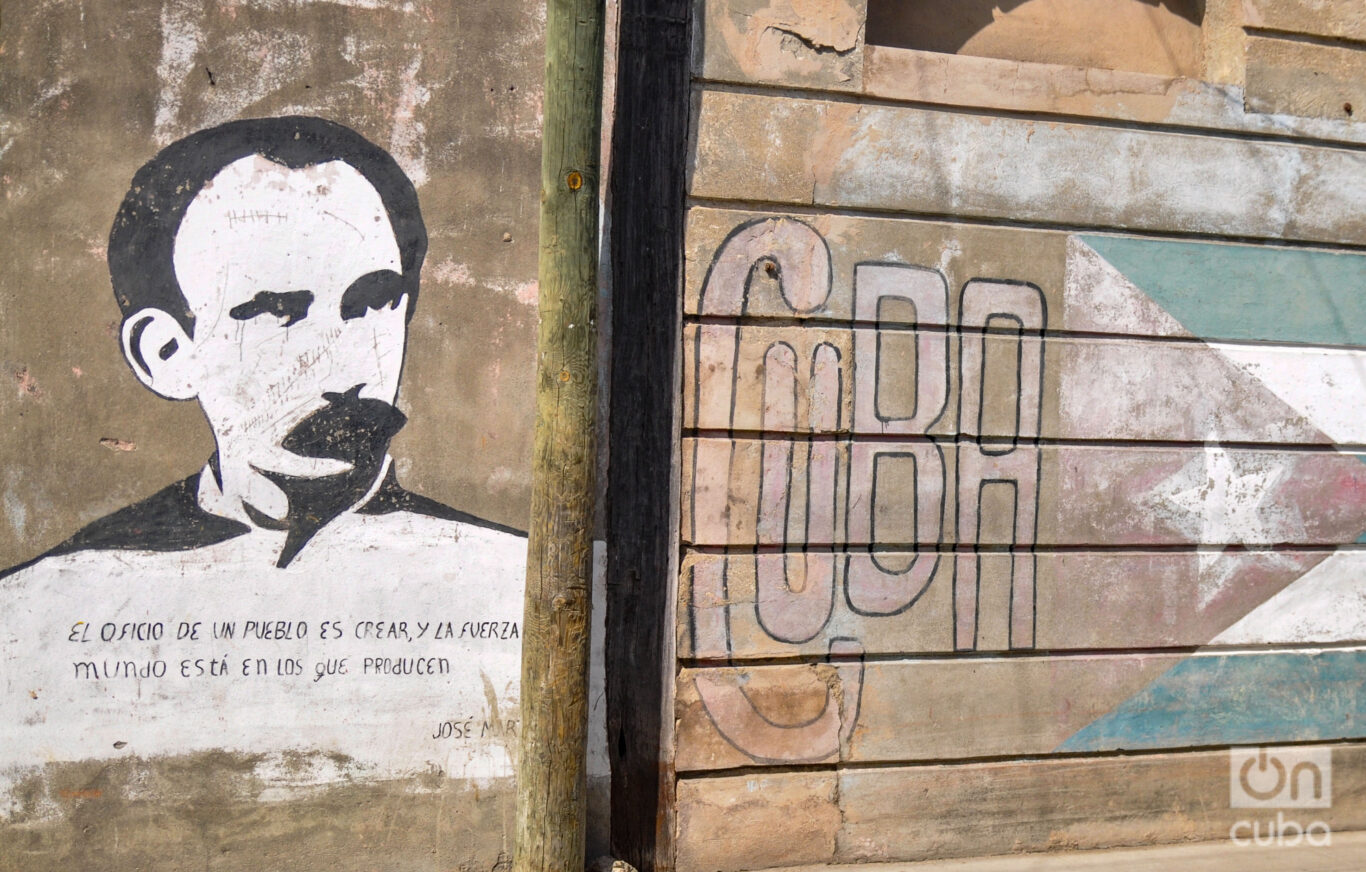

However, in Cuba—and not only there—we have turned Martí into a quarry of single phrases. We cut their texts at convenience, select the fragment that serves our argument and use it as a crutch to justify decisions, silences or slogans. Almost always to cover the lack of one’s own thinking. In this way, Martí ends up reduced to a rhetorical, utilitarian resource, repeated ad nauseam. A friend said, ironically, that if Martí collected copyrights, the country would not have a way to pay them.

But there is something even more problematic than the cut quote: the way in which Martí is pulled. His figure and his work are stretched to one side and another, forced to take sides, forced to confirm closed truths. Each sector appropriates “its” Martí and discards the rest. In this constant tug, his thought loses thickness, flattens, becomes functional and stops being a question and becomes an argument; stop bothering to serve; stop thinking to legitimize.

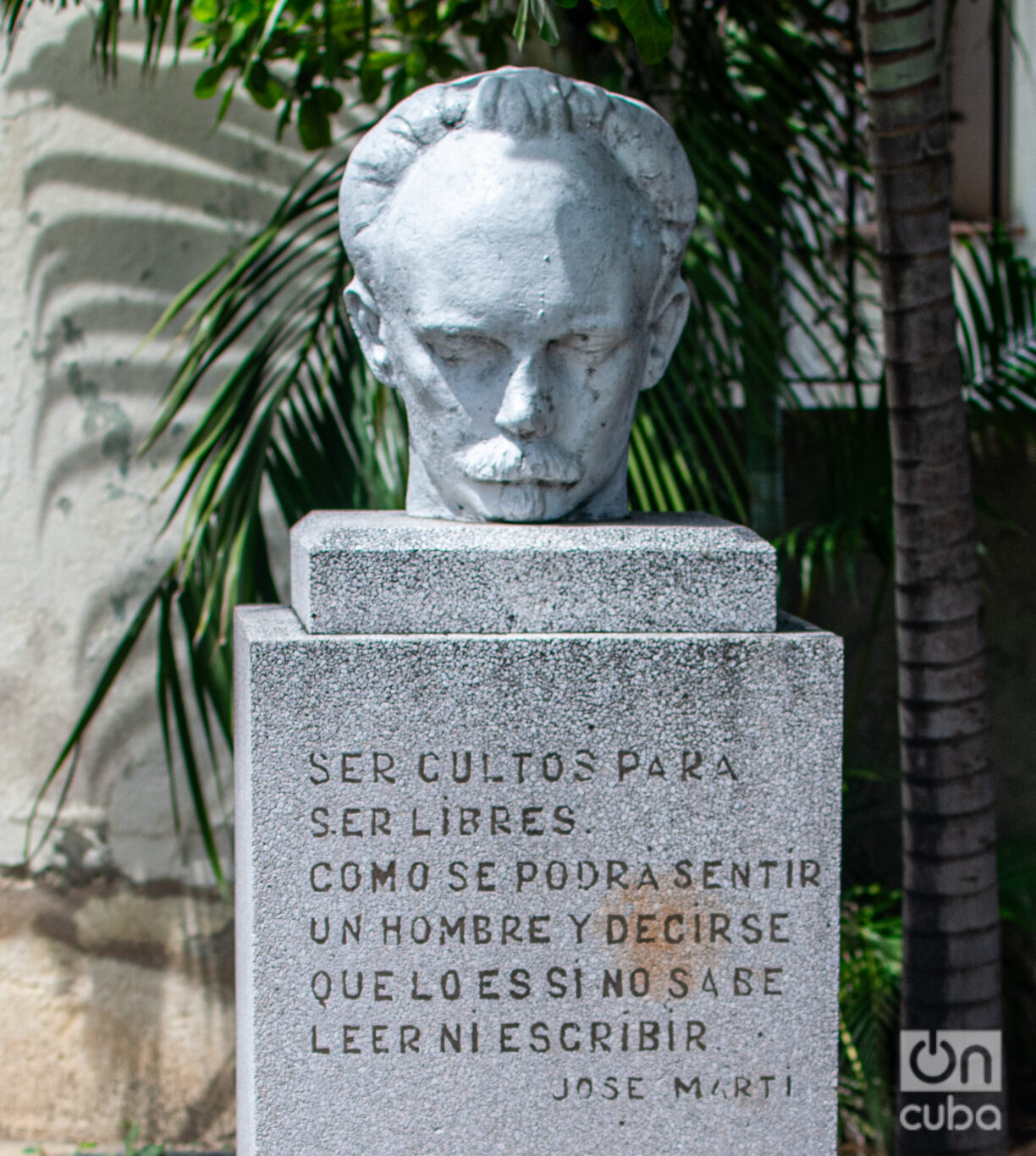

None of that is innocent. Tearing a phrase from its context not only impoverishes thought, but also distorts it. We are accustomed to believing that thinking is repeating what sounds good. That it is enough to quote to be right. Thus, Martí becomes a secular saint, untouchable and domesticated: a plaster bust that adorns, but does not bother; that legitimizes, but does not challenge.

The problem is that Martí, truly read, is the complete opposite. It’s uncomfortable. Argue, doubt, change position. He even contradicts himself, like any living thinker. And therein lies an essential part of its greatness: it does not offer closed answers, but rather questions that remain valid.

That is why his work should not function as a patriotic decoration or as a manual of slogans, but as a permanent exercise of critical freedom. Martí requires us to read, listen, contrast, think. It reminds us that culture is not a moral trophy, but a tool to not be manipulated. And when a quote becomes a slogan—and when thought allows itself to be pulled—it stops illuminating and begins, paradoxically, to darken.

Maybe we have to start with a minimal but urgent gesture: reading again. Read complete. Read without rush. Return to Martí without altars, without manuals, without convenient cuts. Not to use it as a throwing weapon, but to converse with it. To measure how much it still bothers us and how much it challenges us in this present saturated with hollow slogans and curtailed freedoms.