The Venezuelan poet Ramón Palacio Viso, private secretary and adoptive son of José María Vargas Vila (1860-1933), the most widely read writer in Latin America between 1900 and 1950, had the rights to the Colombian’s works and as editor published in 1938 the book José Martí: apostle, liberator.

Palacio Viso, married to a Cuban woman and who died in 1953 in the Santovenia asylum in Havana, accompanied Vargas Vila for 35 years and knew of the controversial man of letters’ devotion to Martí.

The text he compiled includes lectures, articles, commentaries, speeches, letters, and poems. Carlos García-Prada, professor at the University of Washington, dedicated a review to it in the Iberoamerican Magazineon November 11, 1939:

“Being the Colombian pamphleteer —like Martí— a great lover of Freedom, and possessing, as he does, such an upright and independent criterion to see and judge things and men, the portrait that he gives us of the Cuban Apostle is made with sympathy and precision. In phrases of characteristic musicality and bizarreness, Vargas Vila paints us Martí, a simple, spontaneous, candid, direct and confidential poet; to Martí, popular, generous, inspired, captivating tribune; to Martí, creator of a free Homeland, dedicated to a unique and sublime ideal; to Martí, a melancholic, sincere, immaculate, loving man; to Martí, the sacrificed, redeemer and luminous animator of consciences; to Martí, an imposing figure, with profiles that stand out more and more every day in the new American, idealistic and democratic world. Other portraits of Martí will perhaps be more comprehensive than that of Vargas Vila, but it is necessary to know this one to have a full idea of the noble Cuban patriot.“

Palacio was also editor of the book Cuba, Marti and Vargas Vila, Published by Molina y Compañía, in Havana, in 1939.

“Martí’s eloquence was that of the heart”

They met in New York in 1892. Vargas Vila had arrived in the big city to found a magazine and Eloy Alfaro, an Ecuadorian political leader, introduced him to Martí, at that time Consul General of Argentina, and director of the newspaper. Homeland. They had lunch together at the Beavery Street restaurant. A mutual sympathy arose immediately.

Martí’s oratory ability was appreciated three times and he was captivated. On this facet he pointed out in his book The divine and the human:

“Hearing him, one thought about the homeland, about freedom, about goodness (…) Martí’s eloquence was that of the heart. His phrase dark at times, colored, radiant at others, left his lips impregnated with feelings, now vague as the sadness that overwhelmed his soul, now stormy and arrogant as the indignation that possessed him (…) When he began to speak with his forehead Bent over, as if all the pains of her homeland were weighing on her, there was seen the painful vanquished; but when he threw back his powerful head, he shook his hair and launched the indignant phrase of him, the Apostle was seen standing, the one whose condensed verb later became a storm.

He also drew this portrait:

“Soft, gravelly, strangely musical voice. spacious front. Her mouth hidden behind the straight mustaches, fallen over the eloquent lips, to hide them like the alveo of a great river among the hidden jarales.

Latin American bestseller

Vargas Vila, author of almost a hundred books, including the famous erotic novels Ibis, mud flower, red lily, White Lily, Maria Magdalena and an experiment, novel-poem, called SalomeAlthough he was widely read and admired, he also had many detractors who described him as an anarchist, liberal, radical, anti-clerical, egotistical, Freemason, pamphleteer, and pornographer.

Phrases of his are still repeated, taken from fiction or social science texts and circulated orally, from generation to generation.

“Everyone read Vargas Vila, from the intellectuals to those who sit on the doorsteps of the poor streets with no other occupation than to watch the hours go by in the company of a bottle of cheap rum. It is not well known that this self-taught market phenomenon was also an active journalist who founded and directed magazines and newspapers in America and Spain, achieved notoriety as the author of steely pamphlets, and stood out as a politician who defended Latin American independence ideals; He declared himself a sworn enemy of the United States and a fervent anticlerical (…) For his political ideas he was imprisoned and on several occasions had to flee into exile to save his life “specifies the writer Gina Picar in her blog.

mutual admiration

They both enjoyed every encounter. On the eve of his birthday, January 27, 1894, the Apostle tells him in a letter: “I do not forget that I wanted to talk a little later with you and our friend Zumeta, tomorrow Sunday, it is not that I forced you, but that it was not a temporary invitation, and I would really like to enter from you. in my forty-one years. With him carrying his mind, enough…; but see if you can find something of yours that we read. To the snow, Sun.“

And, on March 14, 1894, he wrote to him in another letter:

“I love you the rebellious and American word, like a steel blade with a chiseled fist, with which you cross submissive backs or lying lips: I love the brotherhood with which you bind yourself, in this century of construction and of fighting, with those who pity and serve man, against those who overshadow and oppress him: I love the insight and tenderness with which you looked, at the source of all my energy, which is the indefatigable pity of my heart”.

There are more references about Vargas Vila in the Complete Works of Martí. For example, in the tense days, when he was organizing an expedition to start the Necessary War, he writes on Saturday, October 29, 1894:

“I have just learned that a few sincere hearts are gathering tomorrow Sunday, at eight o’clock at night, in Morillo’s restaurant, —2, 4, 6, West 29th Street— to wish me a safe railway and light sailing for my next trip, and as just yesterday they heard me speak affectionately of your brave pen and American soul and of the liveliness and brotherhood of Duarte Level, one of the revelers came to tell me that they have reserved two seats for you at the family table, table without pomp and few friends.

Hopefully they don’t keep me entertained in New York, and you can come tomorrow to be greeted by the Cubans who already know and love you.

I do not need to praise the pleasure that your friend, José Martí, would give with this.”

In Cuba

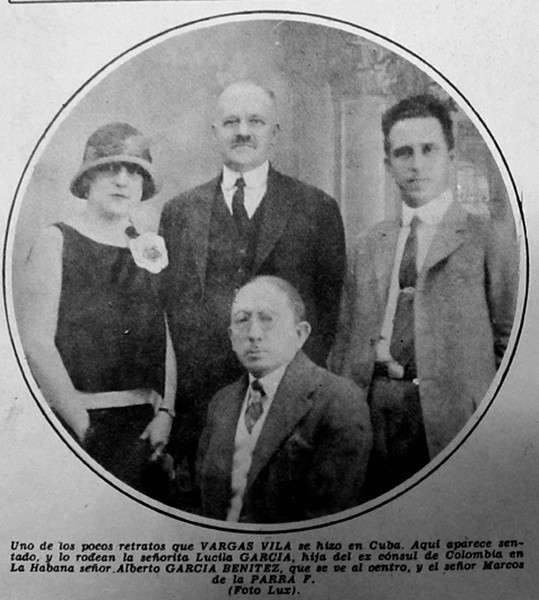

Visiting the Caribbean island, the homeland of Martí, was an old desire of Vargas Vila that he was able to see fulfilled in 1923 when he was going to Mexico. It was a brief stay, by the way. In 1924 he returned. He was then making a tour of different Latin American countries: Argentina, Uruguay, Brazil, Mexico, Colombia and Cuba.

On May 21, he received a tribute at the National Theater in Havana, organized by the National Academy of Arts and Letters. She gave a lecture on intellectual decline in the world. But, without a doubt, an event that marked that visit was his tribute to Martí, in the Santiago de Cuba cemetery, accompanied by Eduardo González Manet, Secretary of Public Instruction.

Interviewed by the newspaper Sunon May 27, confessed:

“The Santiago de Cuba cemetery is one of the most stupendous altars dedicated to freedom in the American world. Martí, Céspedes, the mother of the Maceos, that family of lions, the expedition members of the “Virginius”… the soul trembles and is moved before the sacred tombs. I will always remember the emotion experienced between the whistling pines in front of the marbles torn by the Creole sun.“

There is a note from your Secret Diary, dated July 24, which says a lot about his love for Cuba and Martí, about what they meant to him: “And here I am, once again arriving at the gold and blue beaches of this marvelous island, where the mournful shadow of José Martí seems to extend his arms to receive me. I recover the empire of myself. Bless you!”

About his Cuban days he wrote the works The song of the sirens in the seas of history and The golden portico of glory. The dedication of the first book says: “for having temporarily sheltered my old age and nobly protected my loneliness.” The second book is dedicated to the brothers José Manuel and Miguel Ángel Carbonell y Rivero, who took care of him while he was ill.

In 1926, Vargas Vila returned to Cuba. He was received on May 25 by President Gerardo Machado. He published articles. He appreciated in the press the use of Marti’s work by some opportunists:

“Writing about José Martí in Cuba has become, not a profession, but a business, the most prolific of all businesses; There are people who owe their fortune to the audacity of having muddied the shadow of the Master with their prose. That spectacle is heartbreaking! I saw that fair of the audience without talent, desecrate the ashes of the precursor (…).“

To conclude this review, we return to the work with these notes on the friendship between Martí and Vargas Vila The divine and the human, from the Colombian author:

“Cuba has had many egregious representations of its energy, but the thought of its independence had in Martí the purest, the most eloquent and the most sincere of its voices.

This is how it will remain for the world as the most beautiful gesture of lyrical heroism, the purest accent, the highest voice of unredeemed Cuba, in that twilight hour that preceded the great dawn of its political redemption.

Martí was his Prophet, and he was his Martyr. He will remain in the conscience of America as the greatest tribune of Emancipation, the sonorous and sad Genius of the homeland, the Poet of Liberty, the enormous painful Poet, dying on the tree of his cross.

Sources:

Jose Maria Vargas Vila: The divine and the human, Editorial American Bookstore, 1917.

Navy Journal

Cilha notebooks

Iberoamerican Magazine

http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/Cuba/cem-cu/20150114054555/Vol20.pdf

https://ginapicart.wordpress.com/

https://vargasviladiarios.blogspot.com/