The market has not been, is not and will never be an institution that generates equality. The market has not had, does not have and will never have that goal. The market, through the information transmitted by prices, has been and continues to be the most efficient instrument for allocating scarce resources. According to the famous definition offered in 1932 by Professor Lionel Robbins in his “Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science”, economics is “the science that studies human behavior as a relationship between ends and scarce means that have alternative uses” . It is in this context that the market, through the signals sent by prices, makes the best possible allocation of resources.

The foregoing is particularly important in these times where anti-market “pamphleteers”, disguised as progressives impoverishing idiots, have succeeded in instilling the idea that the market is an inefficient institution for guaranteeing income equality. The market observes the productivity of each resource and remunerates based on that productivity. The same thing happens in the classroom; the teacher awards an “A” to students whose tests reveal excellent knowledge of the subject matter. If the teacher were “progressive”, he would take the average of the grades obtained by all his students and assign that grade to all, regardless of the effort and learning of each of the students. They will all end up receiving an F.

The approach of some “progressive” analysts when they postulate that the problem of income inequality prevailing in some countries has its origin in the market economy system, is totally incorrect. When these analysts are asked for examples of markets more friendly to distributive equity, most point to the developed West and are quick to praise the equity emanating from the market economies of France, Italy, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Finland, England, Ireland, the United States and Japan. If we ask those same analysts for an example in our region of a market economy that generates rampant inequality, the answer always points to Chile, yes, the one designed by the “evil Chicago Boys” under the umbrella of the military government presided over by Pinochet.

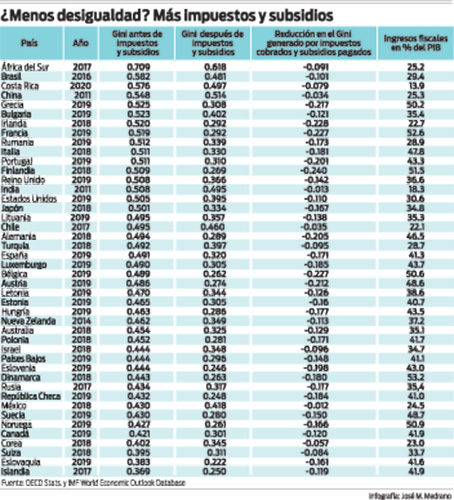

Are the above statements correct? In order to accurately answer the question, we must compare the Gini coefficients (which measure the level of income concentration) that result from the pure and simple operation of the market economy in each of these countries. That is, the Gini coefficient before the State intervenes by collecting its taxes and paying subsidies to certain segments of the population. Remember, the higher the Gini, the higher the income inequality.

The Gini before taxes and transfers reaches the following levels in the countries admired by the “progressives”: Ireland, 0.520; France, 0.519; Italy, 0.511; Portugal, 0.511; Finland, 0.509; England, 0.508; United States, 0.505; Japan, 0.501; Germany, 0.494; and Spain; 0.491. And Chile? 0.495, lower than all the previous ones, except Germany and Spain, which exhibit a practically similar Gini. What does the last thing mean? That the Chilean market economy system, before the State intervenes with taxes and subsidies, generates better levels of distributive equity than those generated by the countries admired by the “progressives”.

It is the State, not the market, that is the institution in charge of guaranteeing that income inequality does not become a factor that destabilizes democracy. To carry out this task, the State basically has two instruments: the taxes collected and the subsidies paid to people. When the Gini is measured after the State has collected taxes and paid subsidies to individuals, important changes are observed in relation to the Gini before taxes and subsidies.

Take the case of France. Before taxes and transfers, the French Gini is 0.519, much higher than the Chilean (0.495). When the French State intervenes and collects taxes amounting to 52.6% of GDP and of that amount transfers a considerable part in the form of subsidies to certain population segments, the French Gini, after taxes and subsidies, drops to 0.292, a level that points to one of the fairest income distributions in the world. That dramatic turnaround is possible in countries whose states appropriate a sizeable share of national income in the form of taxes. What happens in Chile? Simply that, as is the case in most Latin American countries, government revenues are not even half of those achieved by France. In 2020, tax revenue in Chile amounted to 22.1% of GDP, equivalent to just over 42% received by the French State. For this reason, the Gini after taxes and subsidies in Chile barely drops to 0.460. In other words, governments with a large collection capacity (> 40% of GDP) are better equipped to improve distributive equity.

The young president-elect of Chile, Gabriel Boric, has indicated that the time has come to share the honey of the great economic growth that Chile has accumulated in the last 45 years. In 1970, Allende stated that the time had come to distribute the honey from the growth achieved by the governments of Jorge Alessandri and Eduardo Frei Montalva. During the campaign, Boric proposed that, in order to build a fairer Chile, his government would increase tax collections by 8 percentage points of GDP, during 2022-2026, a very ambitious goal. The only OECD countries that have managed to increase their tax revenues by 8 or more percentage points (pp) of GDP in a period of 4 years have been Denmark (1967-1971), Luxembourg (1973-1977) and Italy (1979). -1983), when they registered increases in their tax pressure of 9.6, 8.5 and 9.5 pp of GDP, respectively.

Chile has it difficult. In the first place, it is not the same to manage significant increases in tax revenues in economies with low levels of labor informality than in those with high rates of informality. Last year, for example, 28% of employment in Chile was provided by the informal sector, a level four to five times higher than that exhibited by Denmark, Luxembourg and Italy when they achieved their feats. In Denmark, the citizen earning the average income pays more than half of his income in taxes. In Chile, on the other hand, those who receive labor income equivalent to the average received by the population do not pay income tax. In 2020, the average annual labor income in Chile was 7.6 million Chilean pesos; for that year, the minimum exempt labor income, for income tax purposes, was 8.3 million Chilean pesos. Convincing Chileans that they will have to pay like the Nordics, who very early in the income scale pay 50% or more of personal income tax, is going to be a very difficult task. If, due to the above, the Boric Government chooses to raise the tax rates on company profits (27%) and on dividends paid (or accrued) by shareholders (40%), while legislating that 50% ( or 30%) of the dividends of the companies will have to be paid to the workers of the companies, the return on capital will collapse and not a few Chilean businessmen will begin to ponder the need to diversify their investments towards destinations that are more sensible and friendly to private investment. “Welcome to the Dominican Republic!”. Someone should explain to the Chilean president-elect that, starting in the 1990s, we have witnessed the acceleration of globalization, greater demand for foreign direct investment flows, and greater international mobility of capital. Consequently, governments have fewer degrees of freedom in the design of quasi-confiscatory tax systems, especially if the taxable entity is capital.