Inequality. There is a historical debt of progress and economic integration in the departments that demand the resignation of Boluarte and a new Constitution. The political crisis and repression have been the straws that spilled the camel’s back.

“We are the forgotten ones,” claims Ronald Oré, from Ayacucho, who arrived in the capital more than a week ago for the “Take of Lima”. As I prayed, hundreds of protesters move to the center of the city to demand the resignation of the President Dina Boluarte. The more than 50 deaths during the marches do not daunt them.

But it is not only a question of the demand of the resignation of Boluarte. The demands are also for historical inequality and isolation: “The State doesn’t tell us,” says Ronald Oré, a farmer.

Most of the protesters installed in Lima come from Cusco, Apurímac, Huancavelica, Puno and Cajamarca. Precisely, this part of the country registers high rates of monetary poverty and informal jobs, according to reports from the National Institute of Statistics and Informatics (INEI) to 2021.

Specialists maintain that these regions have lower levels of economic and state integration. Furthermore, they point out that With the self-coup of Pedro Castillo and the subsequent political crisis, these impoverished areas observed that the resolution of their problem was diluted of lack of development. That dissatisfaction triggered the mobilizations at the national level.

Regions in poverty

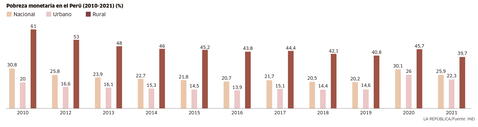

To understand the discontent of the population, it is necessary to take a look at its socioeconomic context. For this reason, LR Data analyzed the latest INEI bulletins on monetary poverty in the country (2010-2021). The numbers were not encouraging.

In 2021, Peru registered a poverty of 25.9%. In other words, the population is in a period similar to that of 2012, with a setback of eleven years.. The figure is even more discouraging in rural areas, where it is double and well above the national average: close to 39% was obtained.

According to Javier Herrera, a specialist from the French Research Institute (IRD), monetary poverty at the national level presented a significant reduction between 2004 and 2016. However, he adds, the figure has stagnated in recent years and has worsened in southern regions.where a group of these remain constantly in economic deprivation.

Infographic – The Republic

Indeed, Ayacucho, Huancavelica and Puno exceed the national average with a poverty that oscillates between 36.7% and 40.6%.. This figure also includes Cajamarca, which is located in the north of the country. Although their number has varied in recent years, they have remained in the group with the highest incidence for more than ten years, according to official data. This implies that, in these areas, the expenses of Peruvians are insufficient to meet their food and non-food needs, understood in health, education, clothing, transportation, among others.

The foregoing, according to Herrera, is expressed above all in the periphery, not in the large regional cities, because there is heterogeneous progress in each of them. Based on the census, the also economist emphasizes that there was a loss of population in favor of the capitals. “Right where the problems, the blockades or mobilizations are being generated, are the secondary towns that are forgotten about public and regional policies. They are claiming problems from behind, from the absence of the State, ”he emphasizes.

Along these lines, Efraín Gonzales de Olarte, an economist at the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP), affirms that the Protestant regions are the least developed and most rural in Peru, dedicated to agriculture and livestock.

“They are the ones with the lowest levels of integration into the market economy and the StateTherefore, the high rate of informality, which translates into low productivity, low income (poverty) and weak integration into State services (roads, education and health)”, he adds.

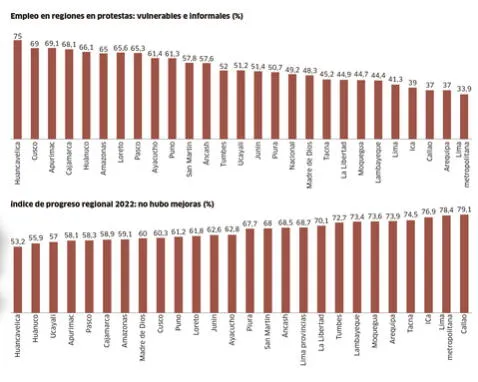

Vulnerable and informal jobs

That poverty manifests itself in employability. Vulnerable jobs in these areas exceed 70%, according to INEI figures. Huancavelica leads the figure with 75%. Then follow Apurímac (69%), Cusco (69%) and Cajamarca (68.1%).. Most people support themselves financially as unpaid families or in self-employment.

With respect to the informal employment rate, the data reaches its total percentage close to 100%. Thus, once again the aforementioned regions begin to appear first. For example, Huancavelica ranks first with 94.8%. Meanwhile, Apurímac and Puno continue with 90.6% and 90.4%, respectively. These three exceed the national average (74%).

Precisely, informality reaches high levels because they are mainly rural, since they are independent workers and without social benefits. Gonzales clarifies that his growth is the result of the “shrinking of the State”, due to the fact that the tax pressure -the contribution of companies to the State- on GDP is 15%, one of the lowest in Latin America; to this is added that there is less investment in sectors such as agriculture, industry and services.

Infographic – The Republic

In this regard, the economist also deepens that informality does not generate a social fabric (unions, associations, political parties, among others), because they maintain precarious jobsare independent or have family micro-businesses.

“The social density is diluted and perhaps the only way to be taken into account is to take roads, cities. Obviously, there is a criminal and illegal minority that takes advantage of discontent for their own benefits.”, he adds, also referring to the demonstrations.

For Herrera, informality is a structural problem linked to the lack of development of the productive forces in rural areas.

These factors contribute to having a low salaried employed population in this part of the country. In Huancavelica, the figure barely reaches 23.5%, almost half the national average (45%).

The outlook is exacerbated by the low wages in these regions. Huancavelica and Puno report that their remuneration is less than the minimum wage. Men get an amount of 937 and 900 soles, respectively.

But there is also a gender pay gap that shows the unequal amounts between men and women, the latter being the least paid, with just over 600 soles. Again both below the national average. Thus, according to Gonzales, the population is not being integrated into the labor market.

slow social progress

Although the INEI figures are for 2021, the Government warned that there were no significant variations for this year. In other words, poverty and labor vulnerability remain. This also reflects the social progress of each region. With those figures down, the demands cannot be met.

The study “Regional Social Progress Index 2022”, by Centrum PUCP, reveals that regions present slow progress in well-being and opportunity for their citizens. Huancavelica, for example, registers 53% in the coverage of basic needs and 48% in well-being fundamentals. This means that there is a high dispersion to satisfy fundamental aspects (water, housing and security) and others related to education and health.

Infographic – The Republic

Hence, these regions have high rates of anemia, child labor and low educational quality. Likewise, not all of them have drinking water or a connection to a public network with excreta.

These problems have been reflected in social conflicts. For Herrera, “this has always been a powerful factor of social mobility. But what is new is the gap between the expectations generated and the non-resolution of them, both by the regional and central governments”.

In the same way, Gonzales adds that to these regions Castillo offered them -demagogically- to improve their lack of development, but with the ex-president’s self-coup, the population understood that Congress emptied it. “It seems that their hopes of improving were annulled, as a consequence they began to protest and then to demand the resignation of President Boluarte, the closure of Congress and new elections,” she reflects.

That inequality triggered the current political crisis against the government of Dina Boluarte. In this scenario, specialists reiterate the need and opportunity to rethink development policies, the economic model and the participation of the State.

Meanwhile, a group of protesters calls for a constituent assembly to address their unmet social demands. But far from addressing the proposals on the table, the president has militarized Puno, precisely one of the impoverished regions, and pointed out that “it is not Peru.” Discontent is growing.

reactions

Javier Herrera, French Research Institute

“Right where the problems, the blockades or mobilizations are being generated, are the secondary towns that are forgotten about public policies. They are claiming problems from behind ”.

Efraín Gonzales, PUCP economist

“(The regions that protest) are those with the lowest levels of integration into the market economy and the State, therefore, the high rate of informality, which translates into low productivities.”