Guido Manini Rios He doesn’t make casual jokes to break the ice. The leader of Town meeting He hardly shows his teeth when he smiles, he listens with his head bowed and a frown. She greets everyone with a kiss and a squeeze to the shoulder.

Don’t you want to sit down? She makes me nervous! a woman says between laughs.

The senator is already standing in front of the 39 neighbors who came to the garage of Roberto González, a retired military man, to listen to him. Outside, night falls in the Santa María neighborhood, between the Maroñas Hippodrome and Piedras Blancas. Behind him hangs the flag of the Cabildo Abierto, overlapping with the national flag. Manini Ríos loosens up and smiles.

–No, no, they see me better that way.

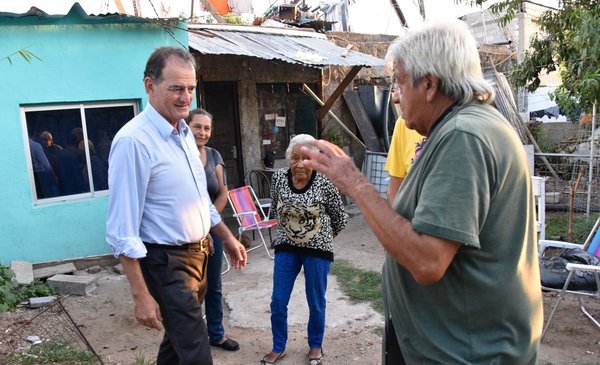

Photo: Federico Gutierrez.

Guido Manini Ríos with residents of the neighborhood in the house of a retired military man

José Techera (81), an old cook in military barracks who now provides support at the picnic area, is one of the first to approach with his cane at the end of the exchange, and extends a hand to Manini.

–My general.

Manini Ríos is determined that the 11% of the votes that the Cabildo Abierto obtained in its electoral debut be a floor and not a ceiling. The polls place the party far from those 2019 records, but the senator sees some opportunities – from political strategy to the methodology of public opinion studies – that may allow him to turn the tide.

Thus, the Cabildo Abierto is going to fight for the votes that the Broad Front holds on the outskirts of the capital and in areas of San José and Canelones. “The most deprived neighborhoods of Montevideo, Canelones and Ciudad del Plata in San José are places with special priority for us, because there we have a strong potential for voters and it is where we vote best“, declared Manini Ríos to The Observer.

“There will be the crux of the electionwhere we have to make our main effort,” warns the leader of Cabildo Abierto. “There are municipalities in Montevideo, like A, where more people vote than in the entire department of Salto. The Broad Front came to vote 80% there, and it is as if it had had 80% of Salto. The effort in the interior is useless if we neglect these essential neighborhoods, with many people asking for someone to listen to them,” poses.

Photo: Federico Gutierrez.

Guido Manini Ríos on a tour of the Santa María neighborhood

The former commander-in-chief of the Armed Forces maintains that “electoral matters are a matter of mathematics.” The numbers show him that in this same area close to Piedras Blancas, northwest of Montevideo, he almost doubled his average number of votes in the rest of the department (14.3% against 8.1%). Although to a lesser extent to the Front, his electoral performance shows him something similar to a mirror to that of the leftist coalitionwhich becomes strong in the west, with Batlle y Ordóñez avenue as a cutting point.

Whites and colorados vote better on the coast, precisely where the Cabildo Abierto falls. In the periphery, the lobbyists estimate, they have the responsibility of disputing the votes of the left.

It is part of that electorate that the political scientist Óscar Bottinelli has described as the subproletariat, a class in which “the level of income is not globally sustained”, which “did not have a structural way out of poverty”, with little organizational capacity -a unlike the working class – and that it is hit by insecurity.

It is there, the expert analyzed, where the “authoritarian father figure” grew, who knew how to embody the red-haired Jorge Pacheco Areco, who at some time took office by Tabaré Vázquez and who was consolidated by José Mujica, until the irruption of Manini Ríos in politics.

The latest Cifra survey gave 2% voting intention for Cabildo Abierto, 4% for Equipos Consultores, 9% for Factum and 5% for Opción Consultores in December, all far from the 2019 vote.

But the director of the latter, Rafael Porzecanski explained to The Observer that those of Manini Ríos and Pedro Bordaberry “are names that increase the intention to vote for the Cabildo Abierto and the Colorado Party”respectively, for being “past high ranking leaders”. The sociologist estimated in the case of the senator, the difference ranges between 3% and 7% with respect to the Cabildo.

From Cifra, meanwhile, which is the one that gave the lowest, they admit that the leader may be better known than his party, although the historical way of measuring the intention to vote is according to the motto, unless an own study is contracted.

around the neighborhood

Manini Ríos is behind the wheel of his Volkswagen Bora.

On Tuesday he was in the 24 de Junio settlement, on Camino Repetto. On Wednesday he tours Santa María. The following week he will be at Punta de Rieles. The local referent who is accompanying is Fernando Da Silva, a former white councilor from Municipality F who since 2009 was a militant in the area for Jorge Larrañaga.

“When Don Jorge died, who for me was a monster, I felt without leadership in the National Party,” he confesses.

The contact in Santa María is the president of the neighborhood commission and neighborhood councilor, María “Marita” Silva, a reference for a picnic area. “I was surprised by some who were from the Broad Front and still came,” she admits at the house on Pasaje D and 20 Metros.

Photo: Federico Gutierrez.

Guido Manini Ríos on a tour of the Santa María neighborhood

The lobbyist promises to “listen to them” and seek a solution “to the extent possible.”

Yaquelin, who is from the Los Milagros settlement on the other side of the ravine, acknowledges that he was waiting for the Minister of Housing, Irene Moreira, to clear up any doubts about the Plan Avanzar, with which the government hopes to eradicate some 120 cantegriles. The lobbyist leader reports that “the idea is that in 10 or 15 years all the settlements will be finished” and promises to refer the questions to his wife.

Neighbors ask about the scope of President Luis Lacalle Pou’s tax announcements and about the shootings at night. Yaquelín says that he cannot “cover the sun with one finger” and he has to ask about the widespread use of drugs in the neighborhood, which he now suffers firsthand with his son.

“We have permanently raised our differences with the drug policy that is followed today in this government, and we are totally against what was done by releasing marijuana,” Manini Ríos clarifies with a firm tone, who often lashes out at the “the scourge of drugs that devastates the neighborhoods” and the “destruction of the family”. The lobbying senator agrees to approve his bill for the voluntary hospitalization of addictsso that they themselves sign their consent before the relapse: “For us that is a flag.”

“Marita” asks him about a possible sentry box for the polyclinic that minutes later they will visit together. Insecurity in the neighborhood is a constant in all the statements, from the mother who came across a shooting on the way to her son’s CAIF to the neighbor who assures: “I already told Heber, either they kill us or I kill them. Here it is no man’s land again.”

“Unfortunately, the police have been separated from the people here. Today they go to the police station at night and hopefully there is a police officer to take their complaint. But there are no people to come immediately to where the problem occurs (…) That It was a policy especially from the years of the Front, commandos were created away from the people. We must return to the police in the neighborhoods. Now we are talking, that two policemen pass by, that after half an hour they return, “he reproaches the leader of Cabildo Abierto.

Manini Ríos stresses to the neighbors his conviction that “the prisoners all work compulsorily, six days a week, eight hours a day”. “It’s the way they get into the habit of working,” he tells them with a frown.

The senator promises “news in a few months” for the debtors, whose project to restructure the debts is being negotiated in the Senate and with which he threatened to take a plebiscite. “This is very hard because there are interests on the other side. These are the problems that interest the people,” he assures his 39 listeners.

Photo: Federico Gutierrez.

Manini Ríos exchanges with one of the neighbors of the Los Milagros settlement

Marita raises her hand.

–Guido, everyone here talks down because they don’t dare to ask you directly. The differences that exist with the coalition, with the president, all that, everyone wants to know where you stand.

Manini is surprised.

– Internal differences? Look, journalists ask me that all the time, I didn’t think you were going to do it.

The neighbors laugh.

–We are aware that we must work seriously and responsibly. For us, the easiest thing to do would be to move to the opposite sidewalk and start hitting the government. But that’s how we left him without majorities in Parliament, in a state of weakness that serves no one (…) Cabildo is constantly trying to see the mountain and not the tree. Every day we have reasons to be angry, but the most important thing is that the coalition works and can have the votes. If the coalition does not work we enter into chaos.

Manini manages to show people his nuances with the ruling party with the same ease with which he manages to quote Aparicio Saravia, José Batlle y Ordóñez, Luis Alberto de Herrera, Luis Batlle, Wilson Ferreira Aldunate and Jorge Pacheco Areco in the same speech.

Minutes later, Marita will lead a tour of the neighborhood. Night has already fallen and Manini marches without signs or loudspeakers announcing it. The neighbors who mate on the sidewalk turn their heads in astonishment when they recognize in him the same person they see on the news. Someone younger, on his bike, follows his pace for a few meters, more out of inertia and novelty than to understand who it is.

A retired military man, last name Mattos, comes out to greet him with a naked torso.

–Oh! you will catch me red-handed!

He promises to put on “a little shirt” to accompany him in the threshing floor. Manini Ríos stops alone before three men who come up to shake his hand at different points.

As when he arrived, the senator greets each one with a kiss. “Good luck and let’s go ‘up hope”, he wishes them. The retired soldier who joined the tour asks for one last photo.

“This one goes to Interpol,” Manini Ríos blurts out, provoking laughter.

The homeowner’s wife comes to tell him that on March 25 he will be 50 years old.

“Come with your wife (Irene Moreira) and we’ll have some wine,” she invites him.

Manini Ríos takes out the account and notes that it will fall on a Saturday. She may not be: during the week he travels the periphery, and the weekends are for trips to the interior.

The Cabildo Abierto leader apologizes. But he promises to come back.