Some 44 photographs that were part of a batch of objects taken as spoils of war by British forces at the end of the 1982 South Atlantic war can now be returned to ex-combatantsbased on a research work carried out by an interdisciplinary group from the Malvinas and South Atlantic Islands Museum, with the collaboration of the prestigious Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (Eaaf).

The work you do the group led by ex-combatant Mario Volpehas a “restorative objective and a deep sense of justice” towards those who “part of their identity and history were taken away” with the theft of these photographs, indicated in dialogue with Télam Edgardo Esteban, war veteran and current director of the Malvinas Museum.

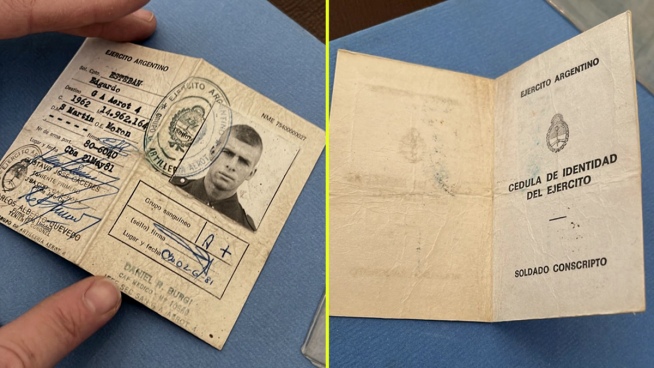

The research team is currently facing the first phase of the work, with the digitization and identification of the 44 photographs who, after intense diplomatic efforts and a criminal complaint, recently arrived in the country along with the military ID restored to Esteban himself.

On April 24, forty years after the war, the director of the Malvinas Museum received his personal documents stolen at the time of the surrender of the Argentine troops, as part of an emotional act at the Palacio San Martín.

In July 2020, Esteban learned that several of his personal belongings, such as his soldier ID and a roll of photographs, had been auctioned off. on the virtual trading platform eBay, in London, as “war trophies”, thanks to the notice given by the journalist Alicia Panero.

The objects were stolen 40 years ago while Esteban. along with other soldiers. he was a prisoner and embarked on the British ship SS Canberra that was taking to the mainland the troops that had been defeated on the islands. From that moment on, a series of actions were unleashed that culminated in the delivery of the belongings, thus establishing a precedent for similar cases.

“Those photographs, in which there may be some of my companions, fThey were part of the lot in which my military ID was auctioned offthat is to say, part of the war booty of all the personal objects that, except for the letters, the British took from us when they requisitioned us when boarding the Canberra,” said Esteban, who is also a journalist and screenwriter.

After 40 years, some of these photographs (the least) are damaged and, therefore, it is difficult to visualize situations, landscapes, locations or who are the soldiers seen in those images. However, a large part of them is in a very good state of conservation despite the time that has elapsed.

The images

A group of Argentine soldiers with their bags marching along the route from the airport to the city and aerial shots of the archipelago and the Argentine Port are some of the images that can be seen in those photographs that -it is estimated- were taken in the initial moments, before the armed confrontation began, on April 2, 1982, which this year marked four decades.

“Because of the characteristics that many photos have, we believe they were taken in the early days therebecause you see comrades with their uniforms still quite intact, in which there are no marks like the ones we had after spending more than 60 days with the mob, with which we were already blended in,” said Esteban, co-writer, along with the current minister of Culture, Tristán Bauer, from the film “Iluminados por el fuego” (2005).

For the director of the Museum, located in the Memory and Human Rights Space, in the former Esma, the task undertaken by the research team It will allow “companions still alive and their families to put together the puzzle” of their own history.

To do this, after the work of digitizing and enhancing the value of the photographs, and with the collaboration of the Eaaf, the Museum team will be in charge of identifying and locating the true owners of these images for their definitive restitution, but also so that their protagonists collaborate in the reconstruction of the facts and situations reflected in them.

It is estimated that there are about 15 Argentine soldiers who appear in the stolen photos, that until recently they remained in British hands and that on April 11 they were handed over to the Argentine Embassy in London by the anti-terrorist division of the British police.

“We want to do a job as seriously and responsibly as possible when it comes to identifications. Search name and surname of those who appear there. There is a story behind each photo and wounds that will surely reopen for many, so you have to do it with a lot of patience and respect,” Esteban said about the request for collaboration with the Eaaf.

The Eaaf is part of the Malvinas Humanitarian Project Plan which, led by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), allowed the identification of 119 Argentine combatants buried without names in the Darwin military cemetery.

For this task, a work team coordinated by the Ministry of Justice and Human Rights developed protocols that would allow each family to obtain information about their loved one who had fallen in the Malvinas.

With this objective, we worked with the ICRC to adapt Eaaf protocols according to the requirements of said institution, an experience that, despite its different characteristics, could be very useful in approaching ex-combatants and their families for the task made, now, by the Malvinas Museum.

“We do not know what the situation of the comrades who were in the Malvinas and who appear in many of those photos is, whether they are alive or not. So, we want to do a job with the greatest care to be able to find some of them and have them help us or give us an orientation about what appears in those images”Stephen said.

In this regard, he pointed out: “We consulted the Eaaf to carry out a procedure similar to the one that this institution does when the remains of the soldiers buried as NN in the Darwin cemetery are identified: give them the information as it corresponds to the relatives, respecting a protocol. We seek to do that work and that is why they are advising us.”

for Stephen, the restitution of these 44 photographs, like that of his military ID, has a “powerful symbolic meaning”, but it also “sets a precedent” on how to end “part of this piracy that exists in relation to the belongings of soldiers that were taken as spoils of war.”

“Making money with things that are personal, like my documents that were sold for 1,350 pounds sterling, seems to me an aberration that cannot exist,” Esteban said.

In that sense, he fought for the existence of “a procedure that allows us to be able to claim” the stolen elements and added that “the recovery can serve to motivate and encourage other ex-combatants to do the same.”

“Rebuild identity from the rescue of our own history” It is for Esteban a central part of this work carried out from the Malvinas Museum, which is recognized in the struggle of human rights organizations and, like Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo with the search for the grandchildren snatched in the last military dictatorship, holds the collective memory.

“In a country where we are still looking for the grandchildren, that I have rediscovered part of my identity in that card is not minor. It seems to me that they are symbols of those times and that construction of struggle. Time does not pass, neither with Malvinas, nor with what those days of horror were like. It is important to have that clarity of what happened to us and what happens,” Esteban concluded.