They are silent men who lean on their rifles and chew tobacco leaves. The steamer that left them on the coast with difficulty avoided the reef and the enemy ships, and had to negotiate with the pirates –raqueros is the technical name, thieves, sea ravens– so that they would not give away the landing.

Dawn breaks over the eastern coastline and the soldiers begin to talk, to walk. There are Cubans, Canarians, Mexicans, renegade Spaniards, a platoon of Americans – led by old General Thomas Jordan –, Poles, Hungarians and some English.

“All of us who were on the peninsula were, according to Spanish law, hordes of freebooters,” writes Manuel de la Cruz about that 1869 expedition, aboard the steamer puppy. Singular chronicler, however, because when that event took place he was an eight-year-old boy.

It is rather a rescue, a cult of the “religion of our past”. Conversations, documents, archives and the exhaustion accumulated by the mambises served De la Cruz to compose his best-known book, Episodes of the Cuban Revolutiongiven to the press in 1890.

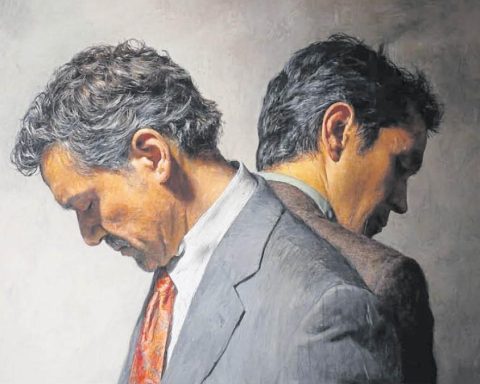

Elegant, ingenious, short-lived – he was killed by pneumonia in 1896 – Manuel de la Cruz is our Stephen Crane. As the author of The red emblem of couragethe Cuban mixed the memory of the veterans with his literary perspective to recount the war of 1868, a “magnificent and forgotten ruin.”

Elegant, ingenious, short-lived –he was killed by pneumonia in 1896– Manuel de la Cruz is our Stephen Crane

The episodes They make up a mosaic of agile and well-told stories –except for two or three monotonous pieces– where the contest reaches the vitality that a history book can never offer. De la Cruz, a Havana native who lived in Catalonia, visited Paris and died in North American exile, was also a kind of spy in the service of Martí.

When the war of 1895 was about to break out, he returned to Cuba, with the mission of sowing discord among the leaders of the Autonomist Party –still hopeful with reforms that Madrid never fulfilled–, studying the terrain and seducing the old insurgents to unite them to the cause. He returned to New York very ill, where he assisted Tomás Estrada Palma as secretary until his death, at the age of 34.

Manuel de la Cruz’s prose fights against itself, reformulates its style and perspective, and not infrequently the manuscript ends up thrown into the fire. In war he finds his voice and plays with death, fortune and disenchantment, which seem to captivate him as much as Crane.

There are memorable pages in the episodes, of an often brutal realism, like the agony of doctor Sebastián Amábile, who loses an eye from a bullet and tears it out so that it does not hinder his escape. Or Captain Larrieta, into whose mouth he went to give a rebound shell, and who, after clicking his tongue, snapped at his enemies: “That’s how I spit out the bullets, like saliva.”

A lieutenant who succumbs to the “indecent and warm neck” of a mulatto woman, the wife of a friend of his, and ends up killing himself out of guilt; a formidable Negro, who disperses a Spanish column by force of shoves and machetes, until he is riddled with bullets; the American Henry Reeve, blonde and freckled, who learns Spanish with a copy of Don Quixote stolen from a dead man

Relentless with what could lessen the fervor in the face of the “necessary war”, Martí praised the book by Manuel de la Cruz and despised ‘On foot and barefoot’, by Ramón Roa

Generals, soldiers, assassins, disenchanted, pirates, deserters –the most famous are the Twelve Apostles, “foam of the bohemian rebellions”–; those are the characters of Manuel de la Cruz. However, behind each subject there is an irrefutable heroism, romantic, puerile at times, capable of moving and very useful to invoke future wars.

Martí was intoxicated by episodes –”I can’t bump into the book without taking it from the table with tenderness, and reading entire pages at once”– and recognized its value as propaganda. Implacable with what could lessen the fervor before the “necessary war”, Martí praised Manuel de la Cruz’s book and despised On foot and barefootby Ramón Roa, also published in 1890.

Roa’s testimony, another classic of campaign literature, recounts a series of defeats in 1871, the “terrible year” of the struggle. It did not arrive at a good time, for Martí; he was bilious, resentful and would scare away the young soldiers. “The book was, clearly, inopportune”, settles the erudite Diana Iznaga, who dedicates a few disdainful paragraphs to Roa in the History of Cuban Literature.

Apart from Martí’s censorship of Roa and the occasional pathos of Manuel de la Cruz, both chronicles are part of our shipwrecked memory.

No one reads or studies them, they are rarely mentioned in universities, and no publishing house on the Island republishes them. They suffer the same fate as the diaries of Martí, Gómez and Céspedes –impossible to obtain–, not to mention José Miró Argenter, Enrique Piñeyro or Antonio Zambrana.

In a country as harsh as Cuba, with empty libraries and political corpses, Manuel de la Cruz’s sentence sounds ironic: “We are the posterity of those men.”

________________________

Collaborate with our work:

The team of 14ymedio is committed to doing serious journalism that reflects the reality of deep Cuba. Thank you for joining us on this long road. We invite you to continue supporting us, but this time becoming a member of our journal. Together we can continue transforming journalism in Cuba.