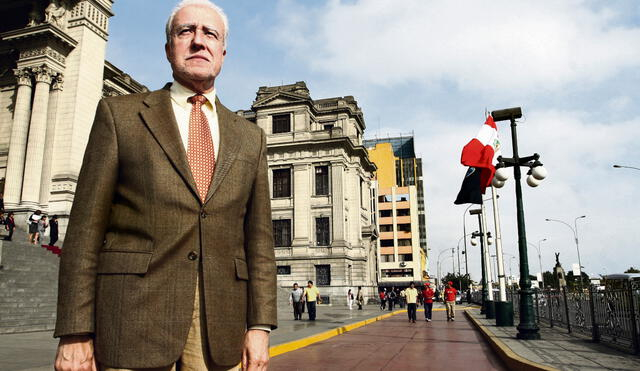

Luis Pasaraa doctor of law and researcher, has just published “Peru as an obsession: the really existing country and actors on the public scene” (PUCP), a selection of his opinion articles in different media covering the last forty years. In them he outlines what he calls “the degenerative process” of Peruvian society and its leaders.

The first chapter of your book is entitled “The Really Existing Country.” I take advantage of this phrase to transform it into a question: what is the really existing country that we have?

It’s a lot of questions to answer in a few words. The central idea in the texts is that Peru is a country in decline, in degradation that is not only economic – of course it is also, as shown by the poverty figures that are published periodically – but above all moral. With this I mean that it is a country where anything goes, where relationships between people guided by calculation and distrust prevail. I am not saying that this is the relationship between all Peruvians, but between many. And above all, it is now a country without direction where the quality of leadership, and not just political leadership, is getting worse. Finally, I would add that it is a country where there is no place for many Peruvians, and this is shown by the increase in immigration in recent years. These Peruvians feel that there is no room for hope in Peru.

There is a constant reference to the idea that social and daily life in Peru is in a permanent process of deterioration. You talk about lost opportunities, repeated mistakes, even about how unlivable Lima is. What are these signs of deterioration?

There are many. And sometimes when I go to Lima I find it difficult to discuss this with people who live in Peru because some of these things can sound offensive. Some of these signs are not so obvious to those who live with them on a daily basis and have gradually accepted them as normal. The most obvious example is the hectic traffic in Lima, or the roads that have a constant number of deaths. But for those who come to the country there are other signs. Perhaps the most important is the lack of trust in relationships. One perceives that no one believes in anyone, at all levels: in the family, in work groups. No one believes in leaders, or in institutions, or in politics. As I am old, I know that the country was not always like this and I have seen how we have made it so. It is a very painful process of realization.

It is a regression.

Exactly.

But do you notice much difference between what you saw 40 years ago when you started writing your columns and what you see now?

I began to see certain signs that announced this deterioration, but I had not yet seen a process like the one now, after all this time. We have had signs that should have been alarm bells and that we did not perceive.

The second part of the book is devoted to what he calls “actors on the political scene.” It also allows us to see their decline in perspective. Some people call them “elites,” but I think that is excessive.

Calling them elite is an abuse of language.

Agreed. Of all the political actors you include in your selection, Velasco comes out the best. He clearly points out the failure of his revolution, but he recognizes a central virtue: having dared to change Peru, to banish the exploitation that existed, especially in the countryside. Is Velasco’s figure not sufficiently vindicated in Peruvian history despite the fact that more than half a century has passed since the coup?

Indeed, I think Velasco dared to change the country and that is what some, a social sector or a group of people, do not forgive him for and will never forgive him for. Time seems to allow people to be better placed, recognizing their value or, on the contrary, forgetting them. In some of the surveys that have asked about the best president Peru has had, Velasco appears. It is a fact. I have a more circumstantial one, which is the interest in Velasco among young people who did not live through his government and want to know what this phase of history was like. I have seen this from the reception my book about Velasco has received. As a country, we keep our history poorly or we simply do not know it.

And in the case of Alberto Fujimori, will people look upon him more leniently over time?

If by history we mean the image that Peruvians have of him, I think it is likely that for a certain time that image will be divided in terms very similar to the current ones. Look at what happened with Haya, a guy who for decades had a divided opinion, to the death I would say. Now, what will happen in the future with that image of Fujimori, the truth is that I do not know and I do not dare to predict it. I have seen so many inexplicable twists in public images that I prefer to be cautious and not go further.

In one of the selected articles you raise a criticism of anti-Fujimorism. Did it fail as a discourse and political action?

The thing is that an anti-APRA proposes something negative, by definition. Anti-APRA triumphed in Peru not because it managed to elect this or that president, but because it domesticated APRA until it became acceptable to those at the top, to economic power. And then, APRA failed in its objective of changing the country, to which Alan Garcia made his final contribution.

His epitaph.

Exactly. Anti-Fujimorism is defined by “Fujimori never again” and so far it has succeeded. It will not be able to change Fujimorism, but it has opened the way for alternatives to the Fujimoris.

I have the impression that when you talk about the Peruvian left, your prose becomes more bitter than when you write about the right. You complain about the lack of democratic leadership, for example, but you complain about the left’s failure and inability to understand the country. What do you think of our left today?

Your impression is probably justified. I never had any expectations regarding the right in the country. So my explanation for that, let’s not say bias but bitter emphasis that you point out when I write about the left, probably comes from the fact that I placed my own expectations on it, that we would become a different country. If bitterness is read in any of my texts, it surely has to do with my own frustration.

And what do you think of the Peruvian left today?

Well, who do we call the left? Cerrón? Verónika Mendoza? Part of the left simply does not exist. That is, there are people who continue to act, to declare, but who have nothing behind them and who also have little in mind regarding what Peru could be or how to make it move forward, have a positive direction and get out of the mess it is in. And people like Cerrón and others use the label of the left, but, in my opinion, they have shown that they have an appetite for power and know how to erase their differences with the right when it comes to agreements that can favor one or the other. We are seeing this in Congress with the alliance between Peru Libre and Fuerza Popular. So, what can we expect from all this? I honestly don’t expect anything.

And what do you think of the right?

Nor does it have anything to offer the country, it is very divided and not so much by political programs or proposals with which they disagree. There are groups that fight for power. This is what happens with all political actors, from the left and the right: no one has a plan to propose to the country, no one has a project. What they do is take advantage of the positions they hold as much as they can, and those who do not hold them aspire to have them. That is the game.

Now, do you still find this whole left-right thing useful given the current circumstances in Peru? I have my doubts.

No, I’ve long since considered it useless. I think it’s an axis that no longer serves its purpose.

What axis would serve Peru? Corrupt and non-corrupt?

It would help a lot, but I think it would be very unbalanced.

Too much weight on one side.

That’s how it is.

I talked to him about lefts and rights because that’s how the book is structured.

Because these are the terms that have been used. One feels that saying this breaks the mold a little, but I think that if we asked the citizen what is left or what is right, he probably wouldn’t be able to define it in terms of the actors he knows because they don’t imply important differences.

Do you think there is a degradation of our political actors?

Without a doubt, without a doubt. Our politicians will go down in history simply because of the investigations they are undergoing in the Public Prosecutor’s Office. I invoke my status as an old man again: I believe that we have never had political actors with these incapacities, but above all with this impudence, this shamelessness with which, for example, congressmen not only approve laws to favour the interests of those who command them, but they approve laws that prevent them from being prosecuted for their misdeeds. In my 80 years of age I have never seen anything like this.

It’s interesting what you say about the shamelessness that we see in politicians today. My feeling is that before, at least, they tried to sell you an idea, even if it was harmful to the country. They packaged it for you.

They were trying to get you excited with a proposal that might sound interesting.

Exactly, that’s over. Rather, they put it as it is: “We want this because we want to protect ourselves.” It’s really impressive.

It’s very impressive. The thing is that since this has gradually become normal, it’s not as impressive anymore because it’s an everyday thing.

What do you think of President Dina Boluarte?

Well, she belongs to this breed of public actors who only seek to stay as long as she can and to grow. That is what characterizes her. She is a woman without merit or ability, who has become president in a totally accidental way, who is bought with watches, who is greedy with trips and honors and who does not care that the polls indicate that she has minimal support and who also does not care that people boo her and reject her in every public appearance she makes. It must seem incredible to her that she has reached that position and of course she wants to enjoy it as much as she can. And she is achieving it, even if it is with steps like a tightrope walker on a tightrope. If jail awaits her afterwards, which is what she deserves, I believe, it is something that at the moment does not seem to matter to her.

You seem surprised that Boluarte remains in office despite his very low approval rating. Other people have expressed that surprise as well. Perhaps it is because in Peru it is possible to exercise power without legitimacy. The idea is not mine, by the way. I was pointed out that in another interview.

Probably. And along with that is the phenomenon that many people don’t care. Many people try to make a living as they can, legally or illegally. They know that the State only causes inconvenience and when a problem arises, you have to ask who gets the bribe. So, in this kind of atmosphere, the truth is that who holds the presidency doesn’t really matter, right?