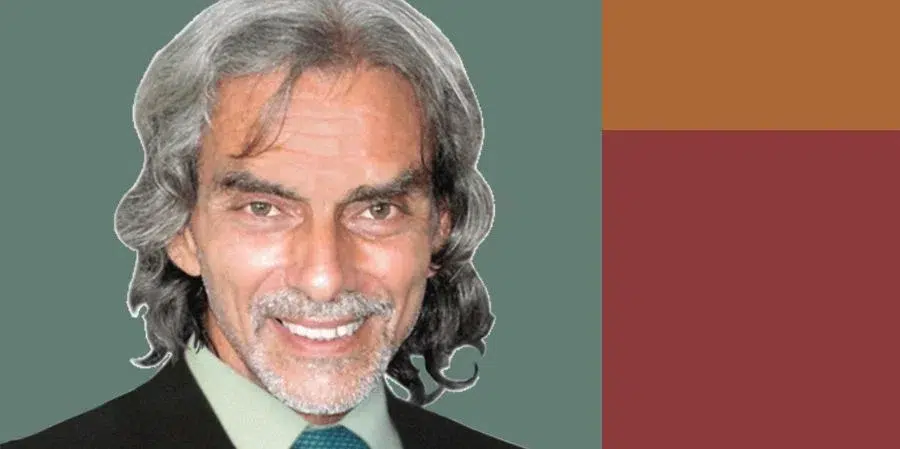

The narrator and journalist write in ‘Cubanet’ about society, art, culture and politics since 2003.

Miami, United States. – In an interview granted to Insularis MagazineCuban journalist and narrator Luis Cino (Havana, 1956) defended his trade as a form of resistance to censorship, explained why he decided to remain in Cuba and drew his own intellectual and cultural itinerary outside the official circuits. “Making journalism apart from control and censorship, telling the real Cuba, is my way of contributing to one day we can live in a better and free country,” he said.

Cino, who entered independent journalism in 1998 at the New Cuban Press Agency, linked his professional practice with a vital and civic need: “I always say that if he were not an independent journalist, he had long lived with rage and helplessness.” He added that he does not intend to abandon the trade, although he longs to spend more time to fiction “when Cuba is a normal country.”

Asked about why he did not exile, he replied: “He weighed more to have my children, my grandchildren, my wife. In addition, I am afraid of not being able to withstand the pain of exile. And, not less important, I do not want to give the pleasure to the regime that I see me fleeing. It would be like giving me up, accepting the defeat. If I have pushed me all the movie, I want to see its end, I want to see its end.

On the immediate present, he stressed the material and mood limitations: “In today’s Cuba today, with so many difficulties and deficiencies, you can barely make plans. It’s just about surviving. I don’t stop writing, I don’t let them come to me and depression.”

Cino said that he never belonged to the official culture: “I did not break with the official culture, I was never within it.” He recalled that, being young, he was rejected in houses of culture and workshops “for the usual ‘ideological problems'”, and that an early expulsion marked him: “They expelled me from the pedagogical detachment in 1974 due to’ ideological problems.”

About his childhood and adolescence at the beginning of the revolutionary process, he said: “My childhood and adolescence ran in the midst of an incessant indoctrination, a maelstrom of changes that were almost always for bad, family tears due to political causes, prohibitions of all kinds and more doubts than certainties.” In a home with fidelist sympathies of his father and brothers, he made him “the black sheep of the family.”

It was defined as “almost self -taught”, favored by a cultural environment that, despite censorship, allowed access to cheap books and non -American cinematographies. “The censorship of the American cinema that governed until well into the 1970s, allowed me to know the best of European cinema and directors of other latitudes such as Akira Kurosawa.”

“I am an incurable, almost manic bluesJazz, the soulhe Country. But also Bach, Mozart, Brazilian music and the author’s song: Serrat, Leonard Cohen, Joaquín Sabina, and mainly Bob Dylan. ”That hobby, banned in his youth for being considered“ the music of the enemy ”, sanctions brought him. (…) Listening to the WQAM and other North American radio stations. ”

The lyrics he copied from Beatles, Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan or James Taylor and the weekly count of American Top 40 They helped him learn English: “I heard them regularly and that allowed me to be so aware of rock and soul as if he lived in the United States and not in Fidel Castro’s Cuba. ”

Cino, which is Columnist of Cubanet Since 2003has written the books The tigers of Dun Dawa (Neo Club Ediciones, 2014), The most happy in the world (Neo Club Ediciones, 2018) and Spring again with Nelson (Bokeh, 2022).

“My first book, The tigers of Dun Dawa“She clarified in the interview – could not be published until 2015.” And, about publishing outside Cuba, he acknowledged: “It is hard not to have recognition in your country, to see you private from the readers of the country of one, which is your natural audience and the one that can best understand you. But it is worse to have to resign that they never publish you and have your work fooled. ”

“The south was familiar to me,” he said about his five visits to the United States between 2015 and 2019, in which he toured “the route of the blues and the Rock and rollfrom New Orleans and Mississippi to Memphis and Nashville. ”He said that those rooms did not modify, but confirmed, his conceptions about that country:” I have never felt strange there, on the contrary. “

At another time of the interview, Cino questioned the persistence of state agencies in part of the cultural field, on and off the island: “There are many artists and intellectuals that not even in exile manage to cut the umbilical cordon with the state protection. It is the result of having formed under a dictatorship has lasted too long and has permeated everything.” And he defined his horizon for a free Cuba: “I conceive of art and culture (…) free[s]without censorship or ideological ties. ”