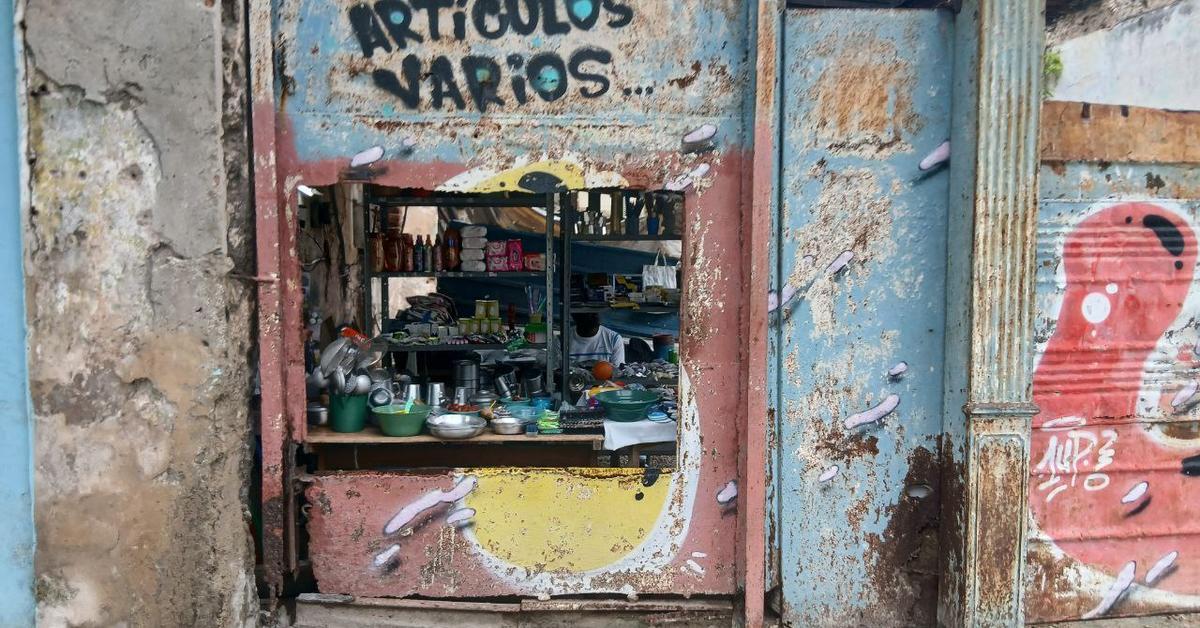

Havana/From the sidewalk of Belascoaín Street, where the noise of the almond trees mixes with the smell of frying and old humidity, a small open rectangle on a corroded wall captures the gaze of anyone who passes by. It is an irregular hole, as if torn out by force, embedded in the remains of a building that lost its splendor decades ago and a few years ago also lost its upper floors. From that collapse, there are stark columns, layers of paint that fall in flakes, and a faded mural where someone tried to draw a sun, perhaps to ward off so much ruin. But in the midst of the chaos, two words painted with a thick, clumsy brush hold an improbable promise: “Sundry items.”

The phrase, written about rust and desolation, has something of an inside joke between the city and its inhabitants. “Several”, yes: several collapses, several roofless rains, several decades of architectural abandonment. But also “several” as an act of faith, as a declaration that, despite everything, someone resists the vacuum continuing to gain ground. There, where there should be silence and dust, a small timbiriche blooms that clings to life like the plants that sprout between the cracks of the balconies.

Behind the peeling paint, a table full of merchandise creates an unusual collage of times and origins

To look into the hole is to discover another world. Behind the peeling paint, a table full of merchandise creates an unusual collage of times and origins. On one corner rest packages of wet baby wipes – imported, with the smell of another country – next to aluminum basins that shine, new, as if they had just come out of the mold of some workshop on the Hill. A few steps further inside, behind a makeshift bar made of planks, the seller arranges jars, funnels, ladles and an assortment of metal parts that could belong either to a kitchen or to a Russian motorcycle from the 70s.

Everything is arranged with a mix of care and urgency, as if each object were a soldier ready for daily combat against shortages. A radio plays softly, almost timidly, while a domestic fan moves hot air that barely manages to dissipate the smell of garbage that comes from the mountain of waste that grows in the corner. Nothing there is comfortable, nor spacious, nor new. But the whole thing works, it pulsates, it breathes. It is a venduta fragile raised on the skeleton of what was a building and what could be, some distant day, an empty lot.

The contrast is brutal and everyday: disaster and entrepreneurship, collapse and the desire to prosper coexist in a space that is not even three meters wide. This coexistence, so Cuban, turns the Belascoaín timbiriche into a small symbol of the entire city: what is about to fall and what insists on rising. Between ruin and ingenuity, between precariousness and inventiveness, beats the same obstinacy that drives so many: sell something, survive, not let life completely collapse.

At noon, a customer stops to look. He’s not looking for anything specific; In Havana no one looks for something specific, one looks for what appears

At noon, a customer stops to look. He’s not looking for anything specific; In Havana nobody looks for something specific, one looks for what appears. And in the small open window among the rubble something always appears: a screw, a sponge, a packet of detergent, a tired greeting from the salesman. Various products, as the poster promises. Various and vital. Various and, above all, possible.

Because here, in this fragment of ruin converted into a store, the city remembers that it is still capable of inventing a minimal paradise where before there was only dust. And that stubbornness, that will to survive among ruins, continues to be the strongest pulse in Havana.