November 8, 2024, 1:38 PM

November 8, 2024, 1:38 PM

The relationship with death and the memory of ancestors takes diverse and fascinating forms around the world, among which the use of skulls or human remains as symbols of respect stands out as a constant. From the Bolivian celebration of “Ñatitas” to practices in Madagascar or Mexico, cultures found unique ways to honor the deceased, blurring the line between life and death.

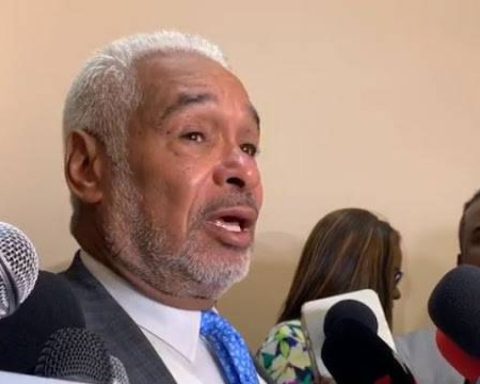

“The cult of the dead is a common ritual in many cultures, as it reflects the continuity of life. These manifestations allow us to connect the world of the living with that of the dead, turning death into a transition,” explains Juan Carlos Núñez, professor of the Hospitality and Tourism Administration degree at the Franz Tamayo University, Unifranz.

In Tibet, the ancient practice of “heavenly burial” exemplifies how Tibetans offer the human body to nature, allowing birds of prey to take the remains to heaven, a symbol of spiritual detachment and communion with the cosmos. Although this practice does not involve the prolonged use of skulls as in the “Ñatitas (Bolivia)”, the similarity lies in the respect for human remains as part of a cycle.

“These rituals, by integrating skulls and human remains, reflect a perception where death is not the end, but a constant presence,” comments Louis Dupont, director of the Museum of Human Bones and Funerary Cultures, France.

In Madagascar, the “Famadihana” or “rolling of the dead” ceremony is a celebration in which families dig up the bodies of their loved ones, change their shrouds and dance with them, celebrating their presence. This practice, although different in form from the Bolivian one, shares the idea that the dead continue to accompany the living.

Vida Tedesqui, from the Cultural Heritage Unit of the Municipal Government of La Paz, points out that “these ritual practices come from pre-Hispanic times and have been seen in countries such as Egypt, Mexico, Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru, and are related to life. and death.”

In Mexico, the Day of the Dead is known for its colorful catrinas, sugar skulls and ofrendas, where the altars are filled with objects that symbolize the tastes and lives of the deceased. In contrast to the direct contact of Bolivia and Madagascar, Mexicans represent their deceased through symbols and figures that evoke their essence.

“The Day of the Dead in Mexico is a vibrant celebration that mixes indigenous traditions with Catholic influences. It is mainly celebrated on November 1 and 2 and is associated with the belief in the return of souls to the world of the living,” says Núñez.

During Holy Week in the Philippines, some communities carry out processions in which skulls and human remains play a visual and symbolic role. These marches include figures and decorated skulls that represent the duality of life and death, with a strong influence of the Christian religion.

“In the Andean vision, the dead are not seen as a fatalistic phenomenon, but rather they fulfill a social function, such as the fruition of crops; It is related to the climatological and agricultural seasons,” comments anthropologist Tedesqui.

As in Bolivia, this procession connects the community with the spirits, a reminder of the finitude and transcendence of life. However, unlike the “Ñatitas,” these remains are exhibited as a public reflection on life and death, with a less familiar and personal approach, and more communal and contemplative.

Bolivia and the “Ñatitas”

In the Ñatitas festival, which is celebrated in Bolivia every November 8, the ritual takes a deeply personal approach, where human skulls, usually those of relatives, are considered intermediaries between the living and the spiritual world.

Decorated with hats, flowers and cigarettes, these skulls become protective figures, to whom devotees thank and request favors, generally, in ‘prestes’ (a popular event in the Andean region that includes various activities around devotion to a saint. , a virgin or another).

“The topic of ñatitas is something extremely interesting today. Even the Catholic Church relaxes the rules, because before they did not allow them to enter the church; Currently, non-Catholic rituals and celebrations are held. It was previously said that this festival was more associated with thieves, drug addicts and prostitutes; However, now it has spread to many people,” says Tedesqui.

Although the rituals of Madagascar, Mexico, Japan and the Philippines have certain differences, they all symbolize a common belief that the deceased are not inactive beings, but figures who live alongside their descendants, guiding and caring for them.

“On the Day of the Dead, iconic elements such as bread of the dead and sugar skulls are used, while in Bolivia the tantawawas stand out, breads that represent the dead and are an integral part of the offering,” concludes Núñez.

Each of these traditions represents an encounter between the spiritual and the human, showing how different cultures find their own language to understand and embrace death. From remains unearthed in Madagascar to decorated skulls in Bolivia, rituals to honor the dead show the universality of the bond between the living and the deceased, adapted to each context.

“On November 8, in the vicinity of the cemetery, hundreds of people go and pay a kind of worship to the ñatitas. Many have them in their homes, they give them particular names and, through dreams, they say they contact them,” concludes Tedesqui.

The human fascination with keeping alive the memory of those who have passed away, whether through offerings, parades, altars or mortal remains, is a constant in the history of humanity. These rituals remind us that, although death is inevitable, it does not completely separate us from those we love and respect.