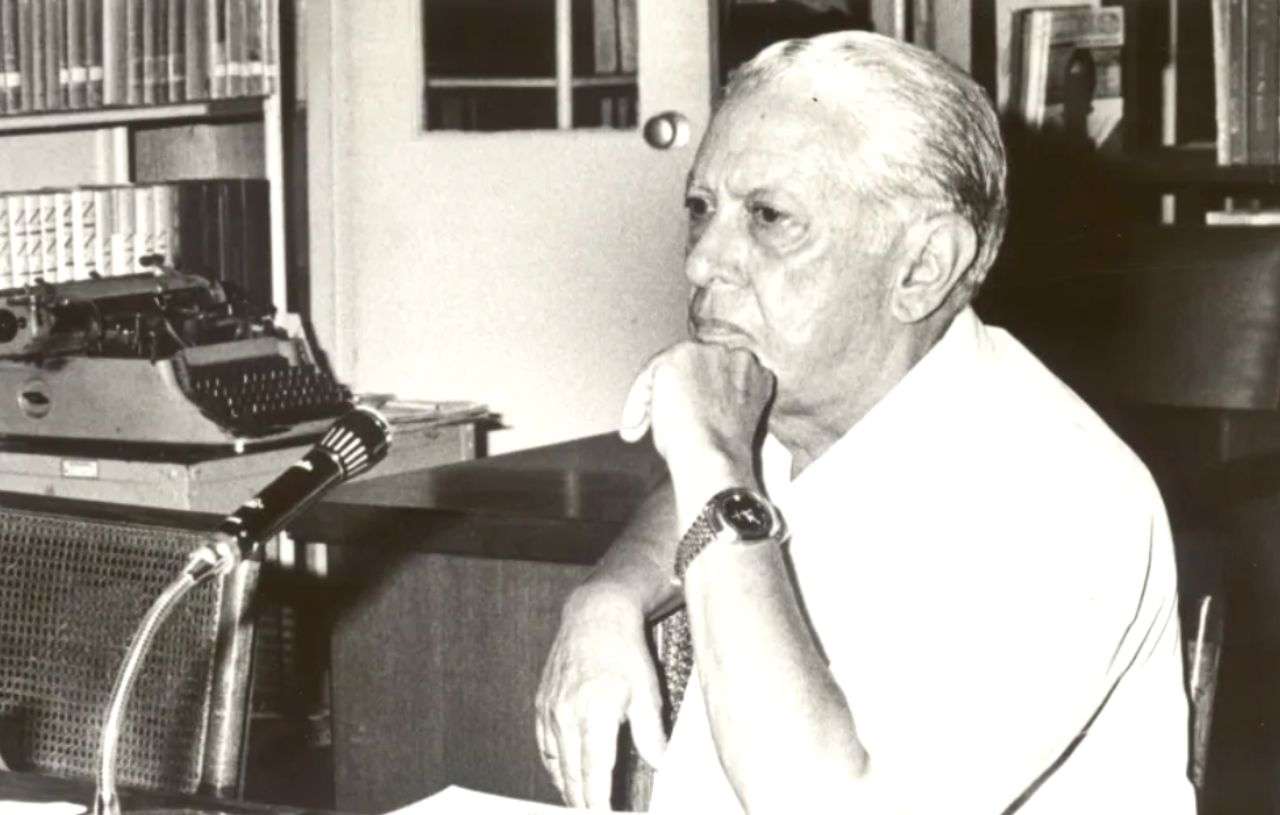

Just concluded the centennial year of Cintio Vitier (Key West, 1921-Havana, 2009) and I received a brief notebook that reveals facets of the youthful life of the Cuban intellectual in his beloved Matanzas, the city where he spent his childhood and in which, in the words of the critic Enrique Saínz, was “the identity of the poet, his perpetual self…”. It is Letters to Mario (1936-1947)with the stamp of Ediciones Matanzas, a bibliographic jewel that brings us closer to the violin student and the poet in training who, from his earliest years, lucidly expressed his love for Cuba and everything Cuban.

To Caridad Contreras Llorca, in charge of the compilation, prologue and notes, we owe the existence of this book that brings together twenty letters sent by the very young Cintio to his friend, the Matanzas musician Mario Argenter Sierra (Matanzas, 1911-Matanzas, 2005), founder of the Chamber Orchestra of Matanzas and first director of the Symphony Orchestra of that city. Jealously guarded for decades, the recipient —already in his old age— donated the epistolary to the Department of Rare and Valuable Funds of the Gener y Del Monte Provincial Library.

The letters (the edition respects the original spelling), testimonies of a friendship that lasted forever, were sent by Cintio from Havana, where he moved with the family in 1935, regarding the appointment of his father Medardo Vitier as Secretary of Education. . Contreras Llorca says in the prologue of the notebook: “The first thing that stands out in this collection of letters is the extreme youth of the sender. Vitier begins to write to his friend Mario—ten years older than him—from his early days in the capital, when he was fourteen years old. In the oldest letters that we can present, from April to September 1937, Cintio has already turned fifteen. Many of the topics dealt with correspond to youth life: studies, exams, outings, news of common friends and relatives…”.

Vitier’s comments on music and its followers also call attention to this stage. At that time he was a violin student, a disciple of Juan Torroella Bonnín (Matanzas, 1874-Havana, 1938), of whom he wrote in one of the letters, dated April 9, 1937: “…Torroella has insisted on presenting me to the Contest sixth year at the Falcón Conservatory. And the serious thing is that he has told me with amazing calmness that I should play a Vivaldi Concerto (possibly the one for A Minor). Well, it’s nothing! That means devoting myself to the violin with an absorbing delight…”.

Later, in the same letter, he comments to his friend Mario: “In these days I have attended two delicious concerts. One of Regino Sainz de la Maza [legendario guitarrista español, amigo de García Lorca]another by Emilio Puyans [flautista, profesor y director de la Orquesta Filarmónica de La Habana]. The first is a guitarist at the level of Llobet [Miguel Llovet, guitarrista y compositor español] or Segovia [Andrés Segovia, virtuoso de la guitarra clásica española). Una técnica depuradísima, un ajuste maravilloso y, sobre todo, una sobriedad y una elegancia de dicción extraordinarias. Pensando en todo esto pienso lo poco que sabemos apreciar lo nuestro; lo digo por Rey de la Torre [José Rey de la Torre, guitarrista cubano] which, much younger chronologically and artistically than Sainz de la Maza, is worth as much as this one, and in my opinion has a superior sound quality. Emilio Puyans is another colossus on the flute…”.

In these lines Cintio’s sharpness and lucidity could already be seen, as well as his love for everything Cuban. At the end of 1937, on December 11, another of the letters attests to his sadness in the face of the economic and cultural depression that Matanzas suffered at the time. “Once again and more substantially in this city, the days that, thanks to your friendship, I spent in Matanzas, exist in me —and forever— with a sad flavor; If I’m completely frank with you, a taste of succinctly sad, without beauty, almost disgusting, unavowable. If I tell you now that I have finally decided on Havana and I put myself completely in it —without forgetting good memories and some sweet magnet from there— it is because modesty is always loved when nudity makes one sick. What desolation, without a secret; what dying in the center of life, undermining it, has Matanzas”.

It was inevitable for the young Cintio to establish the contrast between the “sleeping city” and the intensity of the days in the capital where he had already lived for two years. In this same letter, he lets his friend know about the good novels that he will read during his vacations until January 1938, among them the maelstrom, Colombian José Eustasio Rivera; Don Second Shadow, Argentine Ricardo Güiraldes, and Miss Barbara, by the Venezuelan Rómulo Gallegos. Three of the great works of Latin American literature that Cintio had already read and recommended Mario as required reading; as well as Vendabal in the cane fieldsby Alberto Lamar Schweyer from Matanzas.

Cintio’s literary concerns appear throughout the epistolary that offers information on details of contests and events such as the delivery of the National Prize for Literature to his father Medardo Vitier and that of Poetry to Guillermo Villarronda (pseudonym of the journalist Guillermo González Gómez), referred to in the letter, dated April 12, 1938. A year later, on January 16, 1939, he confesses to his friend that his life has been different since he is at the University, “…because I have met several young people of great quality and Of course, because it happened in time”. In addition, he laments the death of his teacher Torroella and tells her that he has continued playing the violin with Professor Joaquín Molina Ramos.

The last letters published in the book (December 9, 1946 and January 21, 1948) give an account of the wedding of Cintio and Fina García Marruz, and the birth of the first-born Sergio. If read in chronological order, these letters describe the evolution of a young man who, years later, reaches the status of being one of the great scholars of Cuban literature. And it is precisely the revelation of Vitier’s youthful stage that is one of the greatest attractions of Letters to Mario…a notebook that provides references to the life of both friends and to Matanzas and national culture, while taking us into a world full of discoveries for that precocious intellectual who bequeathed us an extraordinary work.

But if the letters themselves have the value of revealing to us a Cintio, perhaps unknown to many, the notebook in its entirety reveals the investigative rigor of the compiler who has not limited herself to the publication of these unpublished epistles until now, but has completed the work with clarifying annotations, fragments of Cintio’s poems and prose, photos of places related to his presence in the city of Matanzas, documents and manuscripts.

Letters to Mario... It is, without a doubt, the testimony of a friendship that lasted a lifetime. The author, librarian and professor with numerous awards and recognitions for her investigative work, says that whenever the Vitier-García Marruz couple visited Matanzas in the 1990s, they had to schedule a meeting at Mario’s house, already having difficulties at that time. to walk. Of him, Cintio wrote in his pamphlet memories and forgetting (2006): “…Fina and I will never forget the versions of the Simple verses that he gave us on the solitary and concentrated piano of his house. I will never forget your aunt Enedina. I will never forget the long, narrow, lateral, secluded patio of her silent house. As I have said elsewhere, he was not from Matanzas. He was, is Matanzas.”