“How dare we let it happen and how can we dare allow it to continue happening,” asked Francisco de Roux, a Jesuit priest and president of the Commission for the Clarification of the Truth in Colombia (CEV), referring to the longest armed conflict from Latin America.

His words this Tuesday were heard by hundreds of people in a theater in Bogotá and by thousands of others who followed the live broadcast of the delivery of the CEV’s historic final report.

The report, entitled “There is a future if there is truth”, is the result of an investigation that began in 2018 and for which more than 14,000 interviews were conducted with 27,000 people in Colombia and 23 other countries.

The work of the CEV, which began after the peace agreement between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas in 2016, has been considered historic.

Through these five questions we tell you why and what the report is about that positions Colombia as a benchmark in memory and reconciliation issues.

1. What is the CEV and what did it deliver?

The Truth Commission is an autonomous institution, although linked to the Special Jurisdiction for Peace that was created as a result of the peace agreement signed with the FARC in 2016.

Its 11 commissioners were chosen after a lengthy process. Among them are some of the most important and experienced academics, social leaders and journalists in the country.

The Commission had a budget of 400,000 million pesos (US$100 million) to fulfill its mandate within three years.

They conducted 14,000 interviews with 27,000 people, including all the living former presidents of the country. They set up 29 truth houses throughout Colombia to collect and disseminate information.

This Tuesday the result of that work was delivered, but not everything was published. Just De Roux’s statement, a sort of prologue, and the chapter on findings and recommendations. During the next two months the other chapters will be published.

There are 24 volumes, about 8,000 pages of report, which will not only have the text version, but will be disclosed, and has been disclosed, through plays, documentaries, exhibitions and various digital formats.

2. What are the findings?

A survey commissioned by the Commission found that 40% of Colombians do not know the history of the war and 35% know it “more or less.”

So the work focused on reconstructing the truth understood as collective and not as a single official and incontrovertible version.

Rather than establishing those responsible, the report seeks to establish the persistence factors that made this war one of the longest in history and in which 80% of the victims were non-combatant civilians.

“We are not going to tell a story of good guys and bad guys or black and white,” a high-ranking source from the Commission told BBC Mundo.

These are some of the conclusions:

– Drug trafficking was not only the financier of the conflict, but it was also a deep-rooted industry that permeated the economy and the political system.

– The conflict not only had armed causes, but also unarmed ones, part of an economic, political and even cultural framework that encouraged the uprising in arms of peasants and excluded political leaders.

– The neoliberal economic model that was implemented for decades, especially after the 1990s, fostered exclusion and inequality.

– The State security model, partly financed by the United States and devised within the framework of the war on drugs, put the Armed Forces in “war mode.” This prevented addressing the conflict as a complex historical process in which the State also played a role as victimizer.

– The exclusion was not only economic: patterns of racial, ethnic, cultural and gender discrimination played a crucial role in the persistence of the conflict.

– The State left vulnerable regions and populations unprotected, especially young people who, faced with the economic crisis and the logic of war present in their territories, were forced to join armed groups as a possible way of life.

3. What is recommended?

If Colombia does not resolve factors of persistence of the war, the conflict “will not end,” Roux said in his speech on Tuesday.

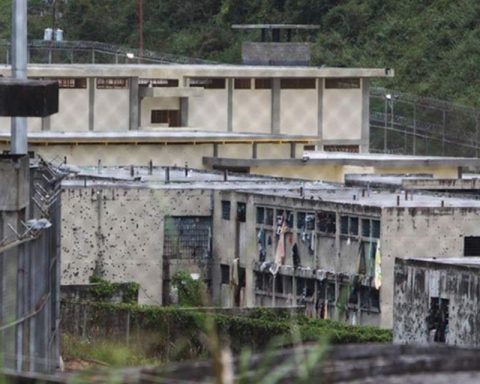

In fact, during the almost four years of work of the Commission, the conflict has intensified in some remote areas, in the form of massacres, assassinations of social leaders and forced displacement of populations.

Just two months ago, the CEV had to cancel several events in sensitive regions due to armed strikes promoted by the groups.

And to face this reality, the Commission makes a series of recommendations to the State, such as creating institutions that follow in the footsteps of its own recommendations, and ethical assertions to Colombians to avoid resolving disagreements with violence.

The Commission’s constitutional mandate ends on August 28. Then an autonomous committee will be formed that will follow the recommendations for seven years and the Commission’s network of allies will be activated (NGOs, governments, multilateral organizations) that hope to contribute to the process.

4. Why was the delivery of the report symbolic?

It is not only the first time that collective work of such magnitude and rigor has been carried out in Colombia, but it is also the first time that those who were on opposite sides for years have been able to listen to each other and, in many cases, reconcile.

During the delivery of the report, for example, a video was seen in which some Embera indigenous people listened to Salvatore Mancuso, a former paramilitary chief and drug trafficker, acknowledge his responsibility in the murder of the leader of his people, Kimmy Pernía.

And on the other hand, former general Oscar Naranjo, who was director of the police, was also seen to recognize that stigmatization is a form of violence and that he contributed to stigmatizing the public university.

In general, it has been a process in which the complexity of the armed conflict and collective responsibility are recognized.

The discourse of the enemies has also been de-escalated and the responsibility has been identified not only of groups outside the law, but also of the armed forces and other sectors of society that are responsible for everything that happened.

But that reading, precisely, is politically uncomfortable for some.

It was very significant that at the beginning of the event, De Roux said that President Ivan Duque had been invited by the CEV, but that he had excused himself because he had an international trip. In his representation was the Minister of the Interior, Daniel Palacios.

So the delivery of the recommendations was made to the elected president, Gustavo Petro, who attended with Francia Márquez, the elected vice president.

In a brief speech, Petro received the text, thanked the CEV and made a call to continue on the path of dialogue.

“I will read the recommendations that are made to me, to the people, to society and to the State. I believe that this effort that is given to the country today cannot be a space for revenge, it has to be looked at and I think that was the objective of the CEV, as an institution of peace, precisely as the possibility of reconciliation and coexistence,” he said.

5. What else will be published?

In addition to the declaration and the chapter on findings and recommendations, in the coming months chapters will be published on the historical narrative of the war, the violations of human rights by the State and the phenomena of resistance to the conflict that intensified the violence, such as paramilitarism.

There is a chapter that will only have testimonies of victims, another on the ethnic populations and young people who were affected by it, one on the exile of millions of Colombians (it is estimated that almost one of the four million abroad fled for violence) and another on the territorial complexity of the conflict.

All the material will be available in a digital transmedia on the CEV page, where anyone can consult not only the report, but also the file and the different contents in audio, video and text format.

During these two months, De Roux is also expected to make an international tour to publicize the report in scenarios such as the UN, the EU and the US Congress.

Remember that you can receive notifications from BBC Mundo. Download the new version of our app and activate it so you don’t miss out on our best content.